On the eve of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), a systematic stocktaking of progress against the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) is taking place. A few months ago, the FAO’s 2015 State of Food Insecurity in the World report outlined progress towards achieving MDG 1 (eliminating extreme poverty and hunger). Over the last week, the focus has been on MDG 4: to reduce the under-five (U-5) mortality rate by two-thirds between 1990 and 2015.

A new report released by UNICEF, Levels & Trends in Child Mortality Report 2015 [pdf], presents estimates compiled by the UN Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation (UN IGME). Similar to the MDG 1 findings, there is much to celebrate at the global level. Though MDG 4 was not achieved, U-5 deaths dropped by 53 per cent, resulting in some 48 million children’s lives saved since the year 2000 – no mean feat.

However, also like MDG 1, there is considerable regional variation. Though the U-5 mortality rate for the MDG Oceania region (red line below in the graph below) is not the highest in the world, the decline in U-5 mortality between 1990 and 2015 was the smallest of all regions, at 32 per cent. While this is far from an insignificant decrease, the U-5 mortality rate of 51 deaths per 1000 live births remains more than double the 2015 MDG target for the region (25 deaths per 1000 live births).

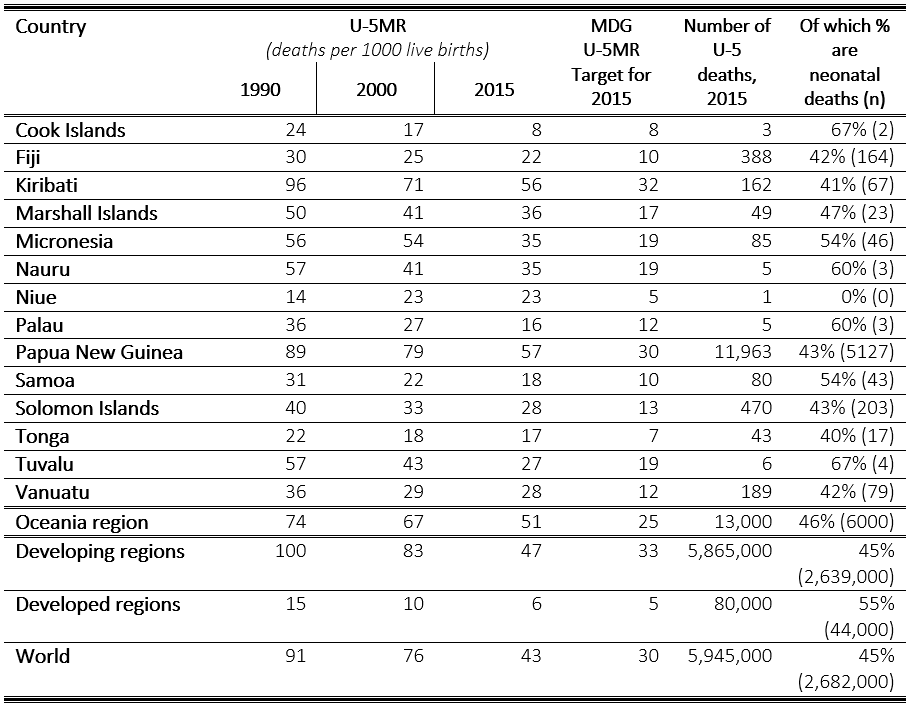

Figures from ‘Levels & Trends in Child Mortality Report 2015’, Table 1

The U-5 mortality rate equates to 13,000 U-5 deaths in Oceania in 2015. As a consequence of population growth, this means only 1000 fewer deaths occurred in 2015 as compared to 1990 (Table 2). Despite this, it’s encouraging to see that the U-5 mortality rate has been in steady decline in Oceania since 1970, shown below. (These data are not included in the main report, but are downloadable from the UN IGME website.)

Data from ‘Global and regional under-five and infant mortality rates and deaths, by MDG Regions’

The challenge now is to how to sustain and accelerate the decline in U-5 mortality. Based on current trends, it is estimated that not only will most Pacific countries fail to achieve the SDG U-5 mortality target by 2030, but will not even do so by 2050 (p. 8). Cook Islands deserves a special mention here: they have already achieved MDG 4. On the other hand, the U-5 mortality rates in PNG and Kiribati exceed both the regional and developing country averages.

Selected data from ‘Statistical Table: Country, regional, and global estimates of under-five, infant and neonatal mortality’ (p. 18–27).

There are pathways forward. For those involved in health policymaking, a key takeaway from the UNICEF report is that the neonatal period (the first 28 days of life) demands special attention, as deaths in this stage of life as a share of all U-5 deaths are on the increase (p. 6-7). In Oceania, neonatal deaths as a share of U-5 deaths increased by some 15 per cent between 1990 and 2015 (p. 7).

Additionally, most deaths among under-fives globally continue to be attributable to infectious diseases (such as pneumonia, diarrhoea, and malaria) and neonatal complications (preterm birth and intrapartum-related complications, sepsis) (p. 8). These are causes that can, in nearly all cases, be successfully and cost-effectively prevented or treated, provided that skilled and appropriately equipped health workers are readily accessible.

Improving access to sexual and reproductive health services (including contraception and safe abortion) can also work to address major upstream causes of neonatal and child mortality, for example through preventing adolescent pregnancy and promoting adequate birth spacing. As of 2012, it was estimated that fewer than 35 per cent of Pacific women were using effective contraception, and approximately one in four women aged 15–19 were already mothers.