Among aid supporters, Tony Abbott’s time as prime minister won’t be remembered fondly. First, there was the disintegration of AusAID for no good reason (not even those invented post-hoc). And then the largest ever cuts to Australian aid. Cuts that were extreme even by the turbulent standards of international aid flows. Cuts that weren’t justified by Australia’s deficit (aid is too small a share of federal spending to have a real impact). And cuts that were so sudden that nothing other than crude heuristics could guide where they fell. Different political parties have different beliefs, and it is fair enough that these influence policy choices, but governing well also means making major policy changes only when they are justified, and making them on the basis of evidence. Justification and evidence were notably absent from the Abbott government’s treatment of aid.

Among aid supporters, Tony Abbott’s time as prime minister won’t be remembered fondly. First, there was the disintegration of AusAID for no good reason (not even those invented post-hoc). And then the largest ever cuts to Australian aid. Cuts that were extreme even by the turbulent standards of international aid flows. Cuts that weren’t justified by Australia’s deficit (aid is too small a share of federal spending to have a real impact). And cuts that were so sudden that nothing other than crude heuristics could guide where they fell. Different political parties have different beliefs, and it is fair enough that these influence policy choices, but governing well also means making major policy changes only when they are justified, and making them on the basis of evidence. Justification and evidence were notably absent from the Abbott government’s treatment of aid.

Now Tony’s tenure is behind us, the big question is whether Malcolm Turnbull’s government will be kinder. There are reasons to hope it will. Turnbull himself appears more capable and considered. And Foreign Minister Julie Bishop’s power has increased. She didn’t appear to support the last aid cuts and she’s shown that she cares about important development issues such as empowering women. Also, the appointment of Steven Ciobo as Minister for International Development and the Pacific is a good sign—a signal there will be more concern for aid.

Yet Ciobo’s appointment is only a signal. And there is a much more tangible act the government could take to show it cares about aid: it could abandon the aid cuts planned for next financial year.

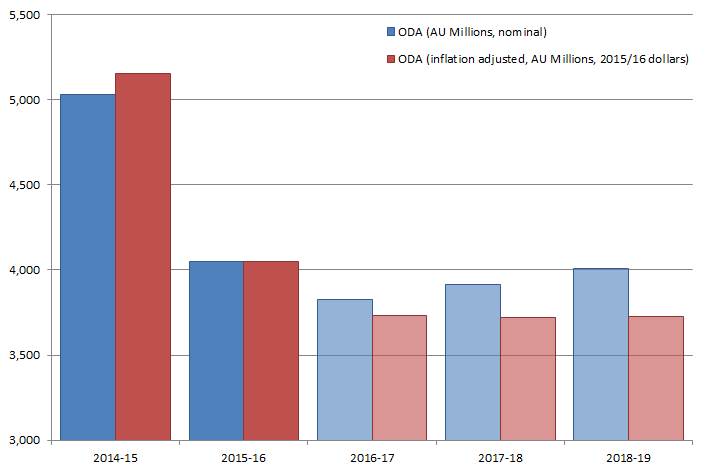

The chart below uses data from the 2015 budget. The blue bars show government aid in non-inflation adjusted dollars, the red bars show the budget once inflation is adjusted for. The first pair of bars shows aid levels prior to the 2015 cut. The second pair shows current aid levels. The subsequent, translucent pairs show planned aid over future years as signalled in the 2015 budget. As the chart shows, aid is currently set to take another hit next year, falling by a further $224 million dollars.

This is not as large as the last cut, but it’s still substantial. It’s more aid than Australia gives Solomon Islands, the third largest recipient of Australian aid. It’s more than the entire Australian country-allocated aid budget for all the countries of Polynesia and Micronesia combined. It’s more aid than Australia gives directly to all the countries of Africa and the Middle East (source: Table 2, p. 5, here).

It’s true that, after next year’s cut, the aid budget is projected to grow so that by 2018 it will almost be back to current levels. But these apparent gains are only rises in nominal amounts–increases in line with projected inflation. As the red bars show, once inflation is adjusted for, aid is set to go down in 2016, and stay down thereafter.

Figure 1: Actual and budgeted Australian Official Development Assistance (ODA)

(Data and source details here.)

(Data and source details here.)

There is an ongoing humanitarian catastrophe in the Middle East. Parts of the Pacific are facing major drought and other climate problems from an El Niño weather event. The broader development problems of countries like Papua New Guinea and Solomon Islands remain as acute as ever. There is no shortage of need for this money. Here in Australia it won’t make a difference though. $224 million dollars is only 0.05 per cent of total federal spending (less than 5 cents out of every hundred dollars the federal government spends). This is so small an amount as to have no material impact on Australia’s fiscal health.

The cut is unnecessary, and the Turnbull government should abandon it, and then, at the very least, increase the aid budget in line with inflation over coming years. Ideally, the government would do much more than this, and it could. But if braver moves are beyond it, canning the coming cut would be a start.

It would be smart politics too. Australians may have been OK with the last cut, but polls show that a clear majority of Australians support or strongly support Australia giving aid (this is not just true of the country as whole but also Coalition supporters) and patience with an ongoing, tight-fisted approach to aid may eventually run out. Meanwhile, NGOs are gearing up to campaign intensively around the next election. Further reducing aid would provide great campaign fodder. Not reducing it on the other hand would go a long way to defusing matters. Internationally, abandoning the cut would set this government apart from its predecessor and go some small way to fostering a kinder image of Australia.

Most important though, is simply the fact that there are many parts of the world where this money is needed. Aid isn’t a panacea, but when given well it helps, and if the current government is concerned with development and global poverty it should cancel the cut.

Terence Wood is a Research Fellow at the Development Policy Centre. His PhD focused on Solomon Islands electoral politics. He used to work for the New Zealand Government Aid Programme.

With the Prime Minister travelling soon to Paris, its also important to look at how the ODA program will be integrated into Australia’s commitment to climate financing.

In Lima last year, Australia committed A$200 million over four years to the Green Climate Fund (GCF) and recently resumed its role as co-Chair of the Fund. These welcome steps follow a lengthy hiatus where the Abbott government refused to support or contribute to the Fund.

A key problem is that neither major political party in Australia has explained how they will contribute our fair share of international climate financing. The current global objective of US$100 billion of public and private funds each year means Australia should contribute more than A$2 billion annually. Recent cuts to the aid budget and the lack of other mechanisms to raise revenue (through carbon taxes, Tobin taxes or the like) means Canberra will struggle to match recent pledges from other OECD countries (Labor relied on the ODA budget for our Fast Start Finance in 2010-12, and refused to use any revenues from the carbon tax for our international obligations).

A central pillar of any deal in Paris will be adequate, predictable and sustained climate financing. With most climate funds currently flowing to major energy and infrastructure projects in larger developing nations, our Pacific island neighbours want to ensure that more revenues are focused on adaptation as well as mitigation, and that funding mechanisms are adapted to the capacities of small island states.

Minister for International Development and the Pacific Steven Ciobo has pledged that Australia will advocate for the interests of our Pacific neighbours at the GCF. But islanders want to speak in their own voice and have created mechanisms – such as the Pacific Small Island Developing States (PSIDS) group at the United Nations – to advance their own agenda on environment and development.

Thanks Nic for an interesting comment. Like Garth you’ve convinced me I was being too conservative in what I’ve asked for. Is the Green Climate Fund something that would normally be expected to be funded from aid? (Sorry, these funds are not something I know as much about as I should). If it is, then given the commitment you mention, not only should the govt not cut aid but it should, at the very least, add $50M/yr if it wants its pledges to be anything more than an exercise in robbing Peter to pay Paul. Terence

I agree with the direction of your call Terence. However if the Turnbull Government is going to signal a change of policy from the continuous aid cuts of the Abbott period and convince electors that it is committed to aid it will need to do more than just avoid the next cut and ensure that the aid budget does not drop below its current 0.25% of GNI.

I can’t imagine the Prime Minister wants to go down in history as the Prime Minister who cut Australian aid to its lowest level of generosity ever but that is what will happen if he only maintains the 2015-16 aid budget in real terms.

Given Australia’s current low rate of growth in nominal GNI, preventing a further fall in the ODA/GNI ratio would not cost a lot of dollars, and as you say, have no material impact on Australia’s fiscal health. But it would have a real impact on Australia’s and the PM’s reputation and on Australia’s aid partners.

Thanks Garth. Very good point.

Thanks Michael.

I’m inclined to think that Bishop opposed the cuts both on the basis of her body language during the budget speech, and also simply because no Minister likes their budget slashed.

That said, as you say, the proof is in the pudding, and if the current government wants anyone to take seriously its claims to being committed to aid it will need to do something tangible — specifically, can the next round of cuts.

Terence

A timely and urgent plea, Terence, with which many furiously agree, but dare not utter publicly. But while reading the political tea leaves is all well and good, let’s see some action rather pin our hopes on signals and shadow puppetry. It’s not at all clear whether, despite her rhetoric supporting women’s empowerment, Julie Bishop’s chief role has been to ameliorate the stakeholders affected by cuts rather than put their case in Cabinet against said cuts. Bishop has never uttered one public statement questioning the cuts, other than to use them as an excuse to whack Labor and blame the all-purpose “budget emergency”. As deft a politician as we have seen, Bishop has managed to deflect any personal responsibility for any of the negative consequences of the changes wrought during her tenure. If her power has increased with Turnbull’s ascension, we will either see some turnaround here or else her actions will have done her talking for her.