Having researched corruption for over fifteen years now, I have heard and read all sorts of hair-raising stories about theft, nepotism, bribery and malfeasance. From Afghanistan to Liberia and from Papua New Guinea to the Philippines, taxi drivers, bureaucrats, civil society activists, business people, donors and more have – often without prompting – spilled the beans on how corruption works in their workplaces, governments and countries.

But only rarely have I been asked for a bribe. The most audacious request came at Roberts International Airport just outside Monrovia, capital of Liberia. After I had handed over my passport, the customs officer told me that my visa was not valid and I had to pay a US$500 “entry fee”.

At first I didn’t know how to react. I knew my paperwork was in order: I had paid for an official visa, and had an invitation letter from a local NGO. But it was late at night and this was my first time in the country. I felt isolated and alone: my phone didn’t work, the counter was dark and all the other passengers had passed through customs.

I tried reason, appealed to his sense of official duty and got angry. Nothing seemed to work. A part of me wanted to get out of there whatever the cost. I put my hand on the cash in my front pocket and considered paying. Finally, I asked to see the official’s boss, who eventually appeared and recognised the name of the NGO that supported my visa. After further negotiation, they let me through without extracting any hard or soft currency.

After a long drive into the city I arrived at my hotel room shaken, and locked the door.

In Papua New Guinea, where I have conducted most of my research, I can only remember being involved with a bribe request once. This time my wife, Anna, was the target.

While I was out conducting research, she was pulled over at a police roadblock on Waigani Drive in Port Moresby. I received the call right in the middle of a meeting at the Fraud and Anti-Corruption Unit. I remember Anna, with a shaking voice, saying something like this:

I just got pulled over by the cops and I’m being asked to pay a fine, but I’m not sure what for. I have given them my drivers’ licence but they want money. If I don’t give it to them they say they are going to arrest me and take me to Bomana prison. It doesn’t seem legit. Can you talk to one of them?

Anna handed the phone over to the cop; in a stern voice, he told me that Anna had to pay him 100 kina because her paper work was not in order.

By this time I had left the meeting and was standing in the sun outside the fraud squad’s then bright blue headquarters located on the outskirts of downtown Port Moresby. I told the officer that we had followed all the relevant rules and regulations; Anna’s licence was relevant and up-to-date, the car was roadworthy and registered. Still he demanded she pay.

I then told him that I had just left a meeting at the fraud squad and I was going back inside to check with senior anti-corruption officials about the legitimacy of his request. “Ok” he said, “she only needs to pay 80 kina”. “I’d better just check”, I said and name-dropped a couple of people at the meeting.

“50 kina,” he replied.

“I’m opening the door to the fraud squad now.”

“OK, 20 kina.”

“I can now see the meeting room, I’m about to go in.”

“Alright, alright. She can go.”

He handed the phone back to Anna and she asked me what to do. “Just drive,” I said, and she did.

She arrived back in our flat at the University of Papua New Guinea still shaking.

These incidents remind me of anthropologist Akhil Gupta’s ethnography of corruption in a small government office in India (paywalled PDF here). Describing both successful and unsuccessful bribery attempts, Gupta shows that the way officials negotiated bribes depended on the social standing and networks of the potential bribe giver. Government officials were more easily able to extract greater sums from the poor and those without the right connections.

In the examples I described above, it was my social standing and connections that helped me get out of a couple of sticky situations. Perhaps if the senior Liberian customs official did not recognise the NGO that supported my visa, or if I had not been in a meeting at the fraud squad when Anna was pulled over, the outcomes would have been different. I am sure a bit of ‘white magic’ – that magical ability of white expats to get away things that locals cannot – also helped.

My examples are also a reminder that there is still so much we don’t know about people’s everyday experiences with corruption. While the study of corruption has increased significantly over the past two decades, most of the literature has focused on abstract ideas about what corrupt transactions involve. Journalists have provided important insights, but, with a few exceptions, most academic scholarship overlooks the quotidian practices involved in extracting bribes from the public. While it would be a nightmare to try to get ethics approval to study bribery, the world needs more scholars like Gupta to provide real-time observations of these practices.

Thanks Grant, this is the most valuable research. Just one suggestion, you need to indicate what type of corruption you are talking about. Corruption that extracts relatively small bribes from the citizens is very common everywhere where the state is weak, choatic and dysfunctional (except for collecting bribes). It is often however understood by the victims-citizens, who give this practice innocent sounding names, lunch-moni or tea money.

For PNG however an equally or possibly more important form of corruption is the grand corruption where money is directly taken from the state or even from the central bank and directly transferred to other, private accounts. Similarly, the corruption with mining licenses and kick-backs on selling of state assets by a few well-connected individuals involves huge sums of money, as we recently read in the Guardian https://bit.ly/pngrexpaki.

I will be writing you to see how we can put some of this research together and paint a complete picture. Corruptology is on the rise! 🙂

At quick perusal, this is wonderful and such useful research Grant. Glad you directed me to it.

Far too often brilliant research such as yours remains as wonderful publications and sits in libraries or other repositories accessible to a limited number of readers and then other interested researchers in the field only.

I sure hope our Pacific media pick on these and share it with policy makers and a wider audience of Pacific citizens, in order to read, reflect and come up with definitions and positions that recognise corruption, as that evil that impedes growth and development in our regions and nations.

Thank you for pointing these out. More late night reading to widen my knowledge base and look forward to more blogs that we can share with our Pacific audiences.

Hopefully with greater research such as yours and visibility on all manner of corruption; those grand scale one’s and on the small scale common bribery, our Pacific leadership and citizens get motivated to call for a strengthening of our INDEPENDENT oversight institutions, to not only improve fiscal governance but to curb common bribery and corruption practices in our respective Nations, small developing Pacific countries and with our developed neighbors too.

Vinaka

Sadhana

I wonder if a landlord not returning Bond to returning overseas students and frustrating efforts with all manner of claims prior to departure home would be considered corruption in Australia?

Or having an application for admission to an Australian University Degree expediated because you knew someone personally, while those without the insider contacts often not even getting a reply to their emails?

What forms of corruption happens in Australia? Did I read something about some Gucci watches being shared around at taxpayer expense?

In Fiji, we have had the much publicized BDO allegations at the regional University of the South Pacific, with the whistleblower Vice Chancellor Pal Ahluwalia kicked out of Fiji by the very Government that came into power via a coup in 2006 with a promise to weed out corruption.

In the eyes of some, including certain legal eagles, the corruption, nepotism, mismanagement as seen by layman’s eyes, was all legal and supposedly within the authority of the former VC.

That the BDO allegations lost the University millions of tax payer and donor dollars looks like will be swept under the carpet, as were similar allegations under the VC, that Rajesh Chandra replaced.

When allegations of millions lost to corruption by the powerful gets swept under the carpet, it is much easier to turn a blind eye to the poor, under paid officer, working a hard day, supplementing his meagre income with a bribe.

Neither is right, but the wrong done by the powerful with access to the best of lawyers and fancy accounting at their disposal, not to mention connections in right places should be excusable.

Do ethics and principles play any role in defining corruption? For if it doesn’t, lawyers are the winners, as are the powerful, for they will steal, as the common men and women do, but legally so, and get away with it time and time again, taking away opportunities from the poor person, who then resorts to the little bribe to make ends meet, which then becomes the way of life in the developing world particularly.

A good contribution to research on corruption in the Pacific Grant would be to study perceptions and understanding of corruption, something I understand Peter Larmour had made a start on…in some communities I know of, if you steal from rich Peta to feed poor Pauls huge family, it cannot possibly be corruption or theft, the bible says so, no?

Wonder if distribution of wealth was equitable in societies, both developed and developing, we’d see less corruption, of grand scales but that common thievery as well?

Hi Sadhana,

Thanks for your comments. You’re right, it is important to understand people’s perceptions of corruption in the Pacific and how activities outsiders call corruption are interpreted by Pacific Islanders. Peter Larmour has certainly contributed a lot to this debate. I’ve tried to pick up where Peter, who is now retired, left off.

Most of my research has been focused on the very questions you raise. I’ve examined how Papua New Guineans interpret and define corruption: https://devpolicy.org/defining-corruption-where-the-state-is-weak-the-case-of-png-20150409/

I have also examined how Papua New Guineans respond to different types of ‘corruption’:

– https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2614179

– https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3333475

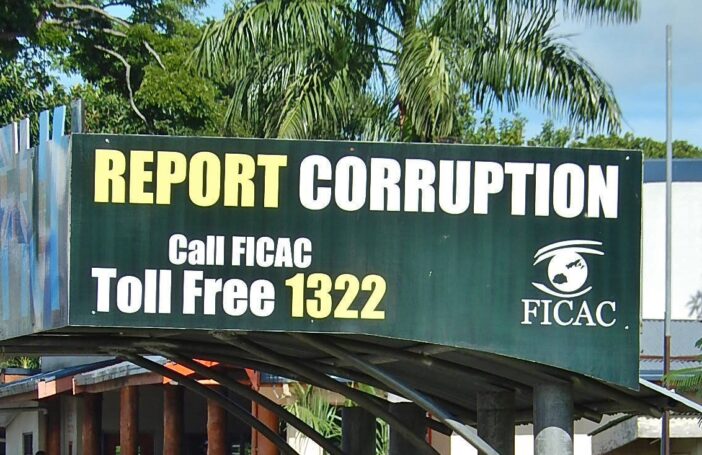

Using data from Fiji ICAC I along with other scholars have examined how those reporting to the FICAC define corruption:

http://devpolicy.org/publications/reports/Trends-in-complaints-to-FICAC-2007-2014.pdf

I’ve also sought (along with Sinclair Dinnen) to reframe debate about the nature of corruption and organised crime across the Pacific region : https://devpolicy.org/dark-side-economic-globalisation-politics-organised-crime-corruption-pacific-20161007/ (in this paper we explain that while Pacific countries are often accused of being highly corrupt, Australia plays a key role in this ‘corruption’ ie by being a destination for corrupt money.)

We certainly need to acknowledge the structural issues – culture, poverty, geography – that shape narratives and accusations of corruption. Much of my work has argued for that. However, I also think there is a role for researchers to shed a light on how corruption actually works. Hopefully this is done sensitively and with an understanding of the broader structural dynamics at play. But if we don’t understand how corruption works on the ground, policy makers (including Pacific Islanders who are leading the charge against corruption in the region) are unlikely to effectively address the types of corruption that Pacific Islanders themselves are worried about.

Best,

Grant

Great post Grant.

Once in Indonesia way back I was posting some items home at the Kantor Pos (via the cheapest shipping possible) and when I got to pay the small customs fee, the customs officer, sitting at his desk watching a small TV, informed me he was ‘closed’ and I would have to wait until he was open. When would he be open again? He couldn’t say, he shrugged. He then tapped his cigarette box in his top pocket and winked. ‘Uang rokok’ or cigarette money is slang for a small bribe in Indonesia. Being the indignant early 20 something I was with my OK language skills at the time I argued with him for a while and put on a show of waiting for about half an hour… but then had to go to work. So I just paid him the cigarette money (Rp 10,000 or about $1 or so in AUD at the time). Suddenly the customs desk was open and I could get my form stamped…

Another time my friend and I had a driver that we hired together for our lengthy commute to and from work and he got pulled over by the polisi one afternoon when the traffic was especially criminal and there was a lot of lane manoeuvring going on by everyone. Suddenly the ‘fine’ tripled as soon as the polisi saw the foreigners in the back seat. Our driver went on a long frustrated spiel about how we were idiots and couldn’t speak any Indonesian and one of us needed to go pee and was angry that’s why he had done whatever he had done (which everyone else on the road was also doing). We could understand everything but just sat there pretending we couldn’t! The polisi tried to talk to us and we just looked confused and he gave up on the whole attempt all together and just waved us off… we were all pretty happy with the outcome! Our driver was furious about police corruption in general though.

Thankfully it has only been small ‘fees’ or ‘taxes’ etc that I have encountered from public officials rather than scary or threatening requests for bribes. For me it was not an issue to pay these if I really couldn’t get out of it, even though I would have some moral indignation about it. But for the average person on a low or middle income it would really cause stress and make it harder to access government services or to earn their living.

Thanks for the comment and examples Ash!