Private sector growth has the potential to create jobs, raise incomes and lift people out of poverty. Recognising this, donors are increasingly using challenge funds to support innovative business models or projects with a potentially high pro-poor impact. While definitions vary, a challenge fund essentially provides grants or concessional loans to projects proposed by businesses that have the potential to solve a defined development problem. Funding is awarded through an open competition based on pre-defined criteria, such as the potential for commercial viability and expected development outcomes.

Increased funding and interest in challenge funds has not been matched by a growth in the evidence base regarding their impact. Heinrich (2013) finds that publicly available results from challenge funds are generally anecdotal, and frequently focus on positive stories without critically examining the impact. In particular, there is little available information on whether challenge funds can create longer-term or systemic change. This lack of evidence poses a risk to challenge funds, which must demonstrate impact to justify their funding. Moreover, it inhibits the ability of challenge funds to learn from their experiences and share this learning with others to improve their performance. Noting this, a recent paper from the Development Policy Centre recommended “comprehensive evaluations” of existing and future partnerships.

To this end, the Donor Committee for Enterprise Development (DCED) has published new guidance for measuring results in challenge funds using the DCED Standard, a practical framework for programs to monitor progress towards their objectives. The DCED Standard encourages programs to measure their own results, clarifying exactly what changes they expect to see and setting indicators to measure progress against them. The guidelines are based on the experience of challenge funds such as the Enterprise Challenge Fund (ECF) funded by the Australian government – one of the first to use the DCED Standard. We hope that these guidelines will strengthen results measurement in future, and also be applicable to other forms of public private partnerships. You can download the guidelines here.

So what can challenge funds do in practice to improve their results measurement? Different techniques might be appropriate for different interventions, such as cost-benefit analysis and cost-effectiveness analysis. But five general suggestions from the guidelines applicable to all interventions follow below:

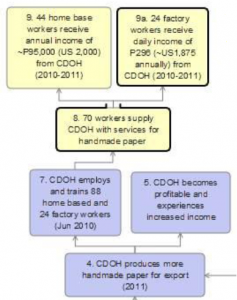

Understand the logic of your program. Challenge funds must make clear how they expect the poor to benefit from each project. Based on the experience of ECF and others, the poor may benefit in three main ways. Firstly, they may be employed directly by a business supported by the challenge fund. Secondly, they may sell inputs to a business, for example, smallholder farmers may sell tomatoes to a tomato processing plant set up with finance from the challenge fund. Thirdly, they may benefit by accessing cheaper or better services, for example, the fund may support a financial service that enables poor people to access bank accounts through their mobile phones for the first time. Given the diversity of projects, all challenge funds should explain how they expect their grantees to benefit the poor. ECF follows the DCED Standard in using ‘results chains’; a simple visual map of activities, outputs and outcomes, and the links between them. An excerpt is pictured on the right, and the full example can be found in the guidelines. Using results chains helps to achieve a shared understanding between the public and private partner, ensures that the desired outcomes are realistic and achievable and becomes the basis for results measurement.

Understand the logic of your program. Challenge funds must make clear how they expect the poor to benefit from each project. Based on the experience of ECF and others, the poor may benefit in three main ways. Firstly, they may be employed directly by a business supported by the challenge fund. Secondly, they may sell inputs to a business, for example, smallholder farmers may sell tomatoes to a tomato processing plant set up with finance from the challenge fund. Thirdly, they may benefit by accessing cheaper or better services, for example, the fund may support a financial service that enables poor people to access bank accounts through their mobile phones for the first time. Given the diversity of projects, all challenge funds should explain how they expect their grantees to benefit the poor. ECF follows the DCED Standard in using ‘results chains’; a simple visual map of activities, outputs and outcomes, and the links between them. An excerpt is pictured on the right, and the full example can be found in the guidelines. Using results chains helps to achieve a shared understanding between the public and private partner, ensures that the desired outcomes are realistic and achievable and becomes the basis for results measurement.

Divide up responsibilities between the business and fund manager. Conventional wisdom is that businesses are only interested in their bottom line. Like most conventional wisdom, this has a large grain of truth, but is not the full story. There is often significant overlap between the interests of the business and public sector, for example, a contract farming business will monitor how much money they pay to their farmers. This is important for the business and also essential for the fund manager who wants to understand changes in farmer income. Consequently, the business and fund managers should clearly divide responsibilities for measuring different indicators, based on their interests and abilities.

Make results measurement useful for the business. Businesses are often interested in results measurement. It can help keep track of activities and outputs, as well as build better relationships with the government. Moreover, monitoring the results of their work helps to strengthen their own value chains, improving their understanding of their customers and suppliers. ECF has commissioned studies that promote learning and dissemination of innovative business models, and provide useful information for the business. For example, one study of loan protection insurance noted that the pay-out is low compared to income from other financing mechanisms, and recommended adjusting the product to address long-term costs. Partnerships should consistently emphasise the importance of results measurement for the business, and customise the system to make it as useful as possible.

Take a portfolio approach. Challenge funds award grants to a variety of different businesses, aware that not all will succeed. Consequently, the fund manager should monitor some projects in more depth than others. Faced with resource limitations, they should prioritise monitoring of more expensive, successful or innovative business projects. As the fund manager cannot identify the most successful or innovative projects straight away, they could monitor everything to a minimum standard and select the most interesting or successful projects for detailed analysis.

Look for market wide changes. As highlighted by a recent working group on challenge funds hosted by the Development Policy Centre, there is still significant disagreement on whether and how challenge funds can change market systems. ECF found their grantees to be invaluable sources of information on this topic, as long as interview questions are concrete and simple. Questions like ‘has any other company shown interest in or contacted you about your business model?’, ‘what new competition do you have?’, and ‘what companies do you buy from or sell to?’ will help gather relevant information. Questions using development jargon such as ‘systemic change’, by contrast, are likely to do little but confuse the interviewees.

This is just a snapshot of the questions addressed in the guidance, but hopefully it is useful and relevant for challenge fund managers. To read more, download the guidelines here, and please write to Results@Enterprise-Development.org with your feedback and suggestions.

Adam Kessler is a monitoring and evaluation specialist and author of the DCED Standard in Challenge Funds.

Hi Tess,

Thanks a lot for your comment – both very important points. The first is particularly crucial as challenge funds are seen as ‘light-touch’, which often translates as ‘cheap’. That’s why prioritisation across the portfolio is important (which I think ECF did well? I remember not all of your projects went for audit)

I also agree with the second point – especially when trying to assess intangible aspects like the additionality of the grant, there’s no substitute for good local knowledge. Which also doesn’t come cheap, and in many places is hard to find at all…

ECF just published a report on their experiences of using the DCED Standard, which is well worth a read – http://www.enterprisechallengefund.org/images/publicationsandreports/Designing%20a%20results%20measurement%20system%20for%20the%20ECF%20Nov%202013.pdf

Best wishes

Adam

Thanks for this Adam, it is a really clear exposition of some key principles. As a (former) country manager for ECF I was involved in numerous discussions about appropriate principles for monitoring projects and I would agree that the current iteration of ECF monitoring and evaluation is much improved from how it started with it being a much truer reflection of these standards. I would add two things to this. One is implied in what you have written here but bears explicit statement and that is funders need to be prepared to invest in monitoring and evaluation and be explicit in recognising that it is likely to be expensive. Exciting and innovative projects located in rural areas with limited transportation links will require site visits and these need to be budgeted for up front. The second (and this applies to other stages of challenge fund activity including formulating criteria for selection, designing application procedures) is the need to know and understand the context in which (potentially) participating businesses operate (and remember that challenge funds work with existing businesses so that is a good location of knowledge about these things) – this includes legal, regulatory, political and cultural issues which may have an impact on the ability of a business to participate in the fund or contribute to monitoring activities.