Papua New Guinea’s roll of voters registered in national elections (the common or electoral roll) has been plagued with problems since at least the 1987 elections. Ever since 1987, the number of registered voters on the roll has exceeded the estimated voting population aged 18 years and over.

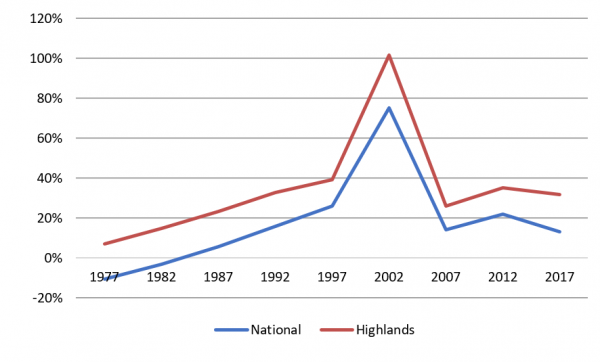

The figure below shows how inflated the roll has been across PNG’s nine elections by comparing the numbers enrolled to vote to estimates of the population. Trends nationally reveal that roll inflation began at 6% in 1987, rose to peak at 75% in 2002, before falling in 2007 and again in 2017 to 13%.

Electoral roll inflation in PNG and in the Highlands, 1977 to 2017

Roll inflation is a problem because it enables people to vote more than once (under their own name, or under the names of others who have died or moved) and because it undermines confidence in the electoral process. The 2002 elections are often referred to as the worst in PNG’s short election history, marked by widespread violence and six failed elections for open seats.

The figure above also shows roll inflation in the PNG Highlands separately, since this is where the problem has always been at its worst.

Breaking the Highlands region down by province can reveal where roll inflation in 2017 was most acute. Calculating population estimates for open electorates in the Highlands is difficult because no reliable data exists for electorates. Making estimates based on the best available data, the table below shows how bad roll inflation was in each Highlands province. Based on these estimates it appears that Jiwaka province had a roll more than three-quarters higher than population estimates, and the next three provinces – Enga, Eastern Highlands and Southern Highlands – each had a roll overstated by more than a third.

Electoral roll inflation in the Highlands provinces, 2017

Roll inflation has been the most visible manifestation of problems with the roll in PNG, but other issues have also been common, including legitimate voters missing from the roll and people being misregistered in the wrong locations.

At times these issues have led to government efforts to address problems with the roll, including creating a new roll and updating existing rolls. The roll has been recreated three times: prior to the 1987, 2002 and 2007 elections. The 2007 roll recreation is generally regarded as the most successful. The 2016 roll update, however, was considered unsuccessful.

Two new features were intended to improve the 2016 roll update. The 2016 electoral roll update process was the first to be decentralised to the provinces, with procedural improvements during enrolment and policies for the process of cleansing duplicate or ineligible voter data. The Decentralised Enrolment System, as it was called, increased local ownership and encouraged legal accountability for the roll update exercise. Another new feature was that the roll was put online so citizens could check their enrolment status.

It is unclear how effective putting the roll online was, as in 2018 only 1 million people had internet access with access unavailable in rural areas, compared to the 4 million votes cast and 5 million registered voters in 2017. Moreover, in some parts of the country, according to several election reports, roll decentralisation led to candidate capture, funding shortfalls, and delay in disbursement of funding to provinces and electorates as reasons for the roll inflation.

Despite a total of K35 million being allocated for the roll update, significant errors persisted including names of deceased and underage persons and the names of voters residing in other electorates.

To add to these problems, it appears that a large number of names of legitimate voters were accidentally removed from the roll during an automated roll clean aimed at removing duplicate names just prior to the election. This eliminated roll inflation in all areas outside of the Highlands, but also deprived a significant number of the right to vote.

The combined effect of this suite of roll-related problems prior to the 2017 election was that in parts of PNG, particularly the Highlands, many people were able to take advantage of roll inflation to vote more than once, while in much of the country many legitimate voters were unable to vote because their names had been accidentally removed from the roll.

Looking forward to the 2022 elections, updating the roll in 2021 is important. Increasing and accelerating the disbursement of electoral funds to the Highlands and to provinces such as Jiwaka and Enga would be a start. Strengthening the capacities and resources of the provincial electoral offices now tasked with updating the roll will be crucial. This will require a process through which powerful candidates are prevented from intimidating or capturing provincial administrations.

A robust roll validation process also needs to be set in place. This could involve an online tool in places where internet access is high, but in other areas there will be no substitute for improved physical validation so that more citizens can confirm their voting status.

A fairer and safer election is in the national interest, and every effort should be made to ensure the 2022 general election has an accurate roll.

Electoral roll data can be found at Devpolicy’s new PNG Elections Database; Regional and provincial estimates for 2018 are from the National Research Institute of Papua New Guinea and from earlier census data, with linear interpolation used for election years. All estimates are inexact.

How can help update the electoral roll?