A lack of decent employment opportunities is a disturbingly prevalent issue in the Pacific. It is not necessary to expound on the reasons why this is so, as reams of paper and dozens of online blogs have described the unique circumstances of small island countries, particularly those in the Pacific (including here [pdf]).

However, not all Pacific island countries are created equal when it comes to employment creation. Some countries have natural resources that can drive respectable employment growth. Some have the right climate and conditions to attract tourists, even within a niche tourism market. Others have colonial connections that ensure some level of migration or trade with Australia, New Zealand and the US.

Kiribati and Tuvalu have none of these advantages. Neither has deposits of natural resources. Tourism is negligible. As overpopulated atolls, Funafuti and Tarawa are particularly vulnerable to climate change impacts and development pressures, which further decrease opportunities for building up domestic industries.

It is thus not surprising that unemployment in Kiribati and Tuvalu is very high, even compared with other Pacific Island countries. While 2,000 school leavers graduate every year in Kiribati, only 20% are able to find cash work. Young women are especially disadvantaged, facing an unemployment rate of over 61% (2010 Census [pdf]). The deficit of decent jobs contributes to poverty, with the proportion of people in Kiribati living below the National Poverty Index in 2006 estimated at 50% (UNDP 2010). Similarly in Tuvalu, there are very few positions that provide a cash income, outside of a small public sector.

That Kiribati and Tuvalu present unique cases even within the uniqueness of the Pacific island region is not new. This idea was explored during the mid-1990s, including by Stahl and Appleyard [pdf] who characterized both countries as “unfurnished” MIRAB (migration, remittances, aid, bureaucracy) countries, subject to such endemic and structural resource constraints that they would always need to rely on migration as a development strategy.

Long before academic studies began to analyze the potential for labour migration as a mechanism for relieving unemployment, the i-Kiribati and Tuvaluans had already spent decades working in other countries aboard merchant ships and in phosphate mines, as a way of supporting families back home. More recently, a few workers have found seasonal employment opportunities on Australian and New Zealand farms.

However, the situation for Kiribati and Tuvalu migration is looking increasingly grim. The number of seafarers from both countries continues to decrease – in Kiribati the number is down to 750 (2013) compared with 1,500 less than a decade ago. Likewise in Tuvalu, just over 100 seafarers were employed in 2014 – a quarter of the number in 2005. Future employment opportunities remain uncertain, and the possibility that seafarer income does not recover, nor is replaced by other offshore employment opportunities, “poses a huge risk to long-term sustainable growth” according to the Tuvaluan government (Tuvalu Government MDG Acceleration Framework 2013 [pdf]), since seafarer remittances alone comprised over 15% of the GDP consistently from 1996 to 2006.

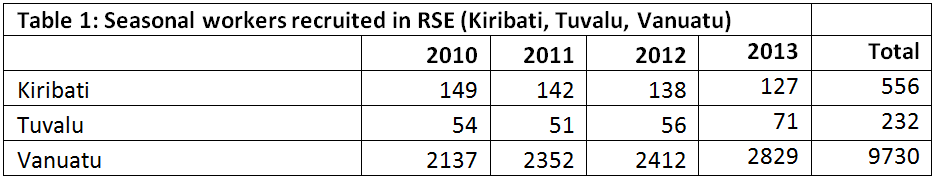

Meanwhile, the number of seasonal workers from the two countries has stagnated. The number of i-Kiribati in the New Zealand scheme has fallen, and Tuvalu’s number has risen only recently but was offset by a fall in Seasonal Worker Programme numbers (to zero in 2013). Kiribati and Tuvalu already face competition from larger Pacific island countries with better resourced departments of labour and better air linkages to Australia and New Zealand. With the introduction of Fiji, Kiribati and Tuvalu’s proportion of places may decrease further, particularly as competition between Pacific island countries is increasingly fierce.

Table 1: Seasonal workers recruited in RSE (Kiribati, Tuvalu, Vanuatu)

Another avenue for migration by Tuvaluans and i-Kiribati is the Pacific Access Scheme, which grants a permanent resident permit to New Zealand (up to 250 people per year from Tonga, 250 from Fiji, 75 from Tuvalu and 75 from Kiribati; a similar scheme also permits migration of up to 1100 Samoans). However, applicants need to secure a job offer in order to receive a permit (and meet other criteria). Few statistics seem to be publicly available on the number of people actually able to take up the permit, and sources from Kiribati and Tuvalu are reporting that even when they meet other criteria, applicants are not able to secure a job offer from a NZ employer.

Another avenue for migration by Tuvaluans and i-Kiribati is the Pacific Access Scheme, which grants a permanent resident permit to New Zealand (up to 250 people per year from Tonga, 250 from Fiji, 75 from Tuvalu and 75 from Kiribati; a similar scheme also permits migration of up to 1100 Samoans). However, applicants need to secure a job offer in order to receive a permit (and meet other criteria). Few statistics seem to be publicly available on the number of people actually able to take up the permit, and sources from Kiribati and Tuvalu are reporting that even when they meet other criteria, applicants are not able to secure a job offer from a NZ employer.

What can be done?

It may be time to accept that Kiribati and Tuvalu are particularly unique cases when it comes to generating domestic job opportunities, and for countries including Australia and New Zealand to give preferential access to Kiribati and Tuvaluan migration. This should be based on the recognition that migration is one of the only mechanisms that would enable these countries to avoid further spiralling into unemployment and poverty.

Here are some suggestions for the Australian and New Zealand governments:

- Introduce special quotas under seasonal worker programs for Kiribati and Tuvalu workers, or other benefits such as longer contracts of up to 12 months working across several farms. Employers are reluctant to contribute to airfares for workers from such remote countries, and the small pool of available workers (as well as the difficulty of conducting direct selection by employers) make it difficult for i-Kiribati and Tuvaluan workers to develop relationships with employers.

- Consider introducing (in the case of Australia) or expanding (in the case of New Zealand) quotas for permanent residence from Tuvalu and Kiribati. In light of evidence that workers are having trouble securing job offers (a requirement under the PAC scheme) help create linkages between the workers and potential employers.

- Finance more regional technical support for Kiribati and Tuvalu to identify opportunities in other labour markets – for example, through the SPC Marine Division, which has expert knowledge of seafarer labour markets.

- Help the Kiribati and Tuvalu governments to identify decent work opportunities abroad for women. As noted in an earlier Devpolicy post on the migration of women, the cruiseliner sector is ripe for engagement with Kiribati and Tuvaluan female workers. Not all will want to migrate, but more opportunities should be created for those that do want to migrate. The same holds for the aged care industry in Australia and New Zealand.

- Upskill more Kiribati and Tuvalu graduates from APTC, USP and Kiribati Institute of Technology and ensure that they have their skills recognized to be able to apply for temporary visas for Australia and New Zealand (noting current difficulties [pdf] of skill recognition).

The governments should also consider which of these measures could be applied in Nauru which, despite low unemployment currently due to remaining phosphate production and employment from the Regional Processing Centre, will soon be facing similar issues unless international labour migration opportunities can be identified.

Not an easy solution, but necessary

These measures will no doubt be sensitive for Australian and New Zealand governments. The rather disappointing results of the Kiribati Australia Nursing Initiative (KANI), for example, which was designed specifically with labour mobility at its heart, will no doubt give pause to linking aid with migration (details can be read in this post). Yet this should not prevent the design of new and better programs.

And, yes, these measures will be controversial among other PICs that are also agitating for increased access to Australian and New Zealand labour markets. However, many Pacific island countries already benefit from seasonal worker programs (Tonga and Vanuatu send thousands of workers each year) and can continue to profit from these schemes. They also have far more scope for creating domestic opportunities in the future.

The suggestions above will not create thousands of labour migration opportunities for Tuvaluans and i-Kiribati. They don’t have to. Even creating labour migration for a relatively small number of people can have huge multiplier effects. Studies suggest that redistribution of remittances in both countries is strong; seafarers support up to 25 people on a single income in Kiribati, with around 17% of the population benefiting [pdf] from the remittances.

The unemployment challenges in Kiribati and Tuvalu are urgent, and are becoming increasingly more urgent with climate change, rising urbanization and other factors that are continuing to put pressure on the countries’ tiny labour markets. Action now to increase these countries’ ability to participate in migration schemes can continue to keep open a safety valve on what could otherwise be an impending social crisis.

Sophia Kagan is a Labour Migration Technical Officer for the Pacific Climate Change and Migration (PCCM) Project with the International Labour Office for Pacific Island Countries, which focuses on the impacts of climate change on migration in Kiribati, Tuvalu and Nauru. Further information on labour migration in the Pacific can be found at the PCCM Facebook Group, and the ILO Suva Labour Migration website. Sophia can be contacted here for further information. The article represents her views and not those of the ILO or the PCCM.

Interesting article. A more in-depth analysis on the reasons why overseas (seafarer and RSE) employment has declined would assist in developing the most suitable types of overseas employment opportunities. For example Vanuatu has increased RSE places because the type of work suits the Ni-Vanuatu who go and they are good at it.

Interesting point about caring for older people from David – it would be useful to identify this and other potential areas of employment opportunity for i-Kiribati and Tuvalu that work for them in order to present feasible solutions.

Sophia, thanks for this contribution. I couldn’t agree more with your assessment. One area that I have long felt required further exploration is the possibility of employment in the aged care sector. Many I-Kiribati and Tuvaluans in New Zealand do this work, and consider themselves extremely fortunate to have a job where they get to spend their days with the elderly, who hold a special place in both cultures. I-Kiribati and Tuvaluans (particularly the women) have a natural and cultural affinity for this kind of work, which is often shunned by Australians and New Zealanders. With ageing populations in both countries, there will be increasing demand for aged care workers, and I think that Kiribati and Tuvalu can help meet this demand. KANI was intended to go some way to satisfying demand, particularly in rural and regional Australia, but the numbers are small, and not every person working in aged care requires nursing training. I look forward to seeing more from the PCCM Project.