Australia’s stance on Pacific migration is again at a turning point, with key features of the temporary ‘guestworker’ model being reconsidered as Labor envisions a more humanitarian approach to regional integration. Alongside the welcome introduction of the Pacific Engagement Visa, the Albanese government has made firm commitments to address another area of pressing concern for Pacific island countries: the prolonged separation of families within the Pacific Australia Labour Mobility (PALM) scheme. As of January 2023, new measures will be introduced to allow PALM workers participating in the longer term stream – the Pacific Labour Scheme (PLS) – to be accompanied by their families, pending approval from their employer.

The potential gains of creating a family accompaniment option within the PLS should not be understated. The social implications of family separation in the PALM scheme are a longstanding topic of discussion across the Pacific. Conversations I’ve held with migrant workers in Australia – as well as remaining family members, community leaders and government stakeholders in Kiribati, Tonga and Vanuatu – have converged on a similar observation: that the economic benefits of the scheme are substantial, but so too are the social costs.

Even when Pacific labour mobility was limited to stints of seasonal employment, concerns were often raised about the prevalence of extramarital affairs, relationship breakdowns, emotional distress, parenting problems, and child welfare issues. With the introduction of the PLS in 2018, transnational family separation became a considerably more worrisome prospect; with workers forced to live apart from their families for up to four years, the likelihood of lasting social consequences increases significantly.

These problems have been addressed in submissions by civil society organisations, have informed the development and piloting of additional pre-departure training for migrant families in Vanuatu, and are a hot topic in regional newspaper coverage of labour mobility schemes. Until now, though, very little research has systematically examined the scope of these issues within PALM.

My new report reveals the nature and frequency of social issues relating to family separation within the PALM scheme, focusing on both the PLS and the Seasonal Worker Programme (SWP). Based on a series of semi-structured interviews conducted in November 2021 with government staff within labour sending units (LSUs) in four Pacific island countries – Fiji, Samoa, Tonga and Vanuatu – it provides the first program-level evidence of the nature and frequency of social issues arising from family separation, as observed by those on the frontline of family welfare reporting. LSUs are responsible for the preparation and departure of workers employed in the PALM scheme; they are also the official or de facto point of contact for family members that remain behind and experience difficulty.

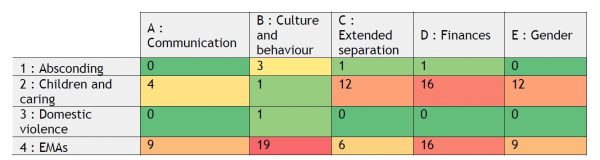

The report finds that extramarital affairs (EMAs) and relationship breakdowns are frequent, but likely under-reported – and have strong thematic correlations with culture shock and behavioural changes in Australia, financial disagreements and misunderstandings between spouses, difficulties maintaining frequent communication, and gender norms and expectations (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Intersections between social issues and associated themes (number of cross-coded entries)

Source: Withers 2022, page 8.

LSU staff also reported widespread concern about the welfare of children separated from one or both parents during migration. The most prominent concern involved the financial implications of relationship breakdowns for dependent children, but interviewees also expressed apprehension about the deterioration of parental relationships and the suitability of alternative care arrangements involving extended family.

Reflecting on the welfare of remaining spouses and children, one participant observed that, “You’ll find that a lot of tensions and conflicts tend to arise once the head of family is away.” Another remarked, “At the end of the day, you’ll have seasonal workers who become seasonal parents or seasonal spouses at this end.”

Consistent with the international literature on transnational family separation, it was clear that these outcomes were not gender-neutral: women – who make up only about 20% of PLS participants – were observed to be more vulnerable to social costs than men.

Findings also indicated that the prevalence of social issues had programmatic consequences, with the volume and severity of complaints raised by migrant workers’ distressed family members creating additional work for thinly resourced LSUs. LSU staff reported having neither the capacity nor specialist training to manage complex and emotionally charged situations arising from relationship breakdowns.

The protracted work involved in resolving these cases is outside the official remit of LSUs, and reportedly detracted from core duties associated with screening and mobilising workers. It also placed unreasonable demands on staff. As one participant commented, “To be honest, most of us are not trained to handle those kinds of situations. And I’m conscious of the fact that if a situation escalates, and we say something wrong, it could lead down a more destructive path like people trying to take their own lives.”

Australia’s commitment to supporting family life in the PLS is a significant step towards addressing these problems, and refashioning labour mobility as a more sustainable partnership with the Pacific. As with the Pacific Engagement Visa though, family accompaniment is a policy that needs to be carefully thought through.

Although specific policy details are still to be announced, serious consideration must be given to the issue of whether workers will be required to self-finance the costs of family accompaniment – including dependents’ travel costs, but also their access to housing, healthcare and education. These costs are substantial and will vary dramatically according to individual circumstances and the location of their employment in Australia, raising questions about which workers will be able to access the family accompaniment option and at what financial cost. Given that the PALM scheme is a labour mobility program with developmental aims, and guided by commitments to gender equality and women’s empowerment, this is not a trivial matter.

It’s important to create policies that expand the options available to migrant workers and their families, but equally important that the design of those policies enables all workers to act on the opportunities provided. If the social costs of PALM are to be meaningfully reduced, migrant families need to be empowered by policies that allow them to decide whether to stay together or travel apart.

Read the full report Rapid analysis of family separation issues and responses in the PALM scheme – final report by Matt Withers.

Disclosure

The author’s research was funded by the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade through the Pacific Labour Facility. The views are those of the author only.

I wanted to share some research that I’ve completed on the Tongan context that could be useful for this. Young people in Tonga who were experiencing transnational parenting indicated they struggled to communicate transnationally with the parent who had migrated, particularly when parallel families had been formed. There were limited opportunities for visits to overcome this, and extended family were not accepted as substitutes for their transnational parent’s absence. To navigate this, young people became increasingly self-reliant, altered their aspirations, and undertook extensive emotion-work to inhibit and conceal their emotional responses to transnational parenting.