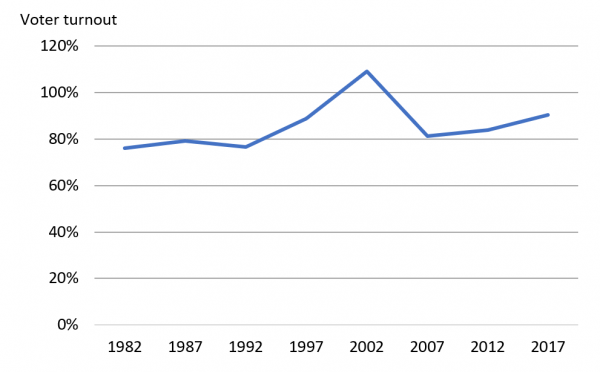

Voter turnout is high in Papua New Guinea. In 2017, approximately 90 per cent of the estimated voting-age population cast a vote, despite PNG not having compulsory voting. This could be a sign that people in PNG are enthusiastic about participating in elections, or it could point to electoral problems. In my previous blog post, I wrote about roll inflation and the potential that came with it for electoral fraud.

The conventional way to calculate voter turnout is as a ratio of votes to people on the roll, but given how inflated the common roll has been, a more appropriate measure in PNG is a ratio of votes to voting-age population (people old enough to be legally able to vote). Using this measure to compare countries in Melanesia, voter turnout in PNG in 2017 was the highest, with recent voter turnout in Solomon Islands at 80 per cent, Fiji at 73 per cent, and Vanuatu at 80 per cent.

Voter turnout (as a share of voting-age population) in PNG, 1982 to 2017

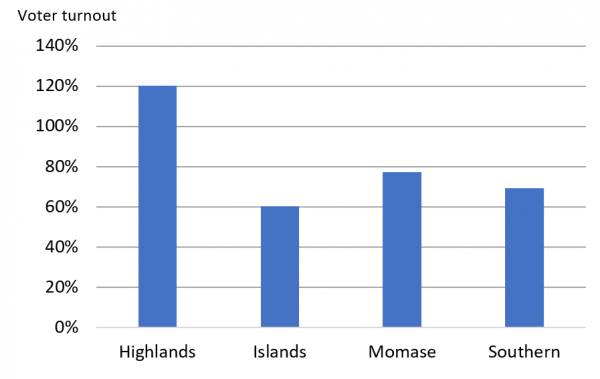

The overall figure for 2017 of roughly 90 per cent of estimated voters voting may not seem too worrying at first glance. However, voter turnout in 2017 varied across PNG’s four regions, as the chart below shows. Voter turnout was 60 per cent in the Islands region, 77 per cent in the Momase region, and 69 per cent in the Southern region. Yet in the Highlands, votes exceeded the estimated voting-age population by 20 per cent.

Historically, voter turnouts have been lower than the national trend in the Islands, Momase and Southern regions. Since 1982, voter turnout in the Momase and Southern regions has been increasing, with Momase’s voter turnout growing from 66 per cent in 1982 to 77 per cent in 2017, and Southern region’s increasing slightly from 67 per cent in 1982 to 69 per cent in 2017. Voter turnout in the Islands, however, fell from 81 per cent in 1982 to 60 per cent in 2017. It is unclear why voter turnout in the Islands is now lower than in other regions.

Voter turnout (as a share of voting-age population) by region, 2017

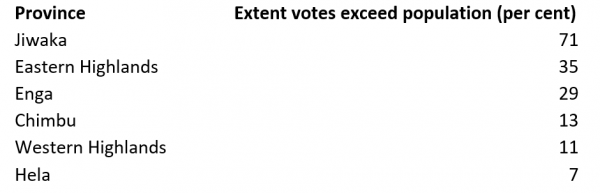

The Highlands region is different, with votes exceeding the voting population in the previous five elections. Examining the 2017 election, it is possible to pinpoint the problematic Highlands provinces. As the table below shows, votes exceeded population by the most in Jiwaka, Eastern Highlands, and Enga. Provinces where votes exceeded population the most were also those with the greatest roll inflation, with Jiwaka the biggest culprit in both the 2012 and 2017 elections.

Since each voter votes twice, one for their own (“open”) electorate and one for the provincial seat, the sum of votes for all electorate seats in a province should be equal to the votes cast for the provincial seat. This is true for all provinces except the Southern Highlands, where the open seat total votes exceeded provincial votes by 37 per cent. Voter turnout was 96 per cent when the provincial vote is used but 132 per cent when open votes are used.

Highlands provinces where votes exceed the voting-age population, 2017

A voter turnout well in excess of the voting-age population in any part of the country is cause for real concern. It indicates that in places voters are taking advantage of an inflated roll to vote more than once, and the 2017 election is instructive. In 2017, implausibly high voter turnout reflected other electoral issues as well. Indelible ink – a tool supposedly designed to indicate people have already voted – was abandoned early in many Highlands voting booths. Further, police personnel were deployed late to some places on polling day. Candidate capture of the appointment of polling officials also led to unrealistic voter turnout.

In 2017, these problems allowed instances of ballot stuffing through underage voting, open voting, block voting (representatives voting on behalf of entire communities), proxy voting, and family voting. One report found that 11 per cent of all respondents surveyed said they had voted multiple times.

The 2017 elections were allocated K400 million, of which K121 million was spent on security. Given the problems of 2017, a better 2022 election will require more – or at least more efficient – election expenditure. Effective coordination between police and the Electoral Commission is needed around the polling schedule. More polling officials and police will need to be posted to wards with large rolls. Preventing capture and intimidation by powerful candidates will require a more transparent process of appointing polling officials and in the counting process.

Many countries worry about their voter turnout being low. In parts of PNG, the opposite is the problem. Realistic voter turnouts will be a crucial test of the fairness of the 2022 PNG elections.

Sources: Electoral vote data can be found on the PNG Elections Database. Accurately estimating the voting aged population in Papua New Guinea is a challenging task, owing to problems with censuses in the country. Population estimates were put together with the assistance of Terence Wood, and estimates here are the best possible based on available data. However, the numbers are only estimates. We estimated population data for elections from 1982 to 2012 using census data and linear interpolation to estimate population in election years. Census data from 1980 to 2011 come from census information provided at: https://pacificweb.org/home-page/. The 2017 population estimates were taken from ‘Regional and provincial population estimates for 2017’ calculated by C. McMurray from projections in McMurray. C. and Lavu. E. (2020) ‘Provincial Estimates of key Population Groups 2018-2022‘, Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea: National Research Institute. We are very grateful to Dr McMurray, NRI and Pacific Web for their excellent resources. Voter turnout rates for Solomon Islands were calculated using census and election data. Turnout rates for other countries can be found on the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance website.

Of relevance to this issue, the following biometric verification news:

“Papua New Guinea pilots biometric voter rolls

Fingerprint and face biometrics will be used for voter enrollment and electoral roll verification in Papua New Guinea, according to Loop PNG.

Voter registration and biometric enrollment for Kupiano Ward 5’s local level government by-election will be conducted by the PNG Electoral Commission. Local government documents will subtract deceased voters and add those who have turned 18 in the ward to the eligibility list.

PNG Electoral Commission Acting Deputy Commissioner Simon Sinai announced the pilot will take place from October 3 to 7, 2020. He also said the government agencies responsible for the project can overcome the challenges it will entail be working together.”

Source: https://www.biometricupdate.com/202009/innovatrics-biometrics-remove-200000-ineligible-voters-from-electoral-rolls-in-guinea

After 45 years of political independence, PNG must seriously reform its electoral system. This report and many other similar reports have clearly identified alarming flaws in the PNG voting system. It must now be a serious cause for concern among all Papua New Guineans because voting genuine and honest political leaders in the next election going forward, through a safe and robust electoral process will ensure the right caliber of leaders are voted into Parliament. Over the last 45 years, little has been achieved through socioeconomic and political independence while in the development space, the country has been lagging behind in all sectors. PNG cannot continue to regress while other small developing economies progress forward with good political leadership.