An interesting evaluation has just been released by DFAT of Australia’s assistance to PNG to help it hold elections over the last decade.

The evaluation estimates that the PNG Government spent $US207 million on the 2012 elections, and the Australian Government spent another $US35 million. This takes the total cost per voter to $US63, the highest in the world. The typical cost of an election is apparently US$5 per voter.

What’s more, elections are getting more expensive in PNG. The report estimates that the 2007 election cost 68% more than the 2002 election and the 2012 election cost 54% more than the 2007 election, so that the 2012 election was 2.6 times as expensive as the 2002 one – and all those numbers are after inflation.

Costs might be increasing, but that doesn’t mean that quality is improving. The evaluation finds that the 2007 election was better than the 2002 election (the “worst elections ever” and “a debacle”), but that the 2012 election was worse than 2007. For example, the 2007 election rolls are estimated to have had half a million “excess voters” (more names than there should have been). This was an improvement from the 1.4 million excess voters on the electoral rolls in 2002, but the number increased again to 900,0000 in 2012.

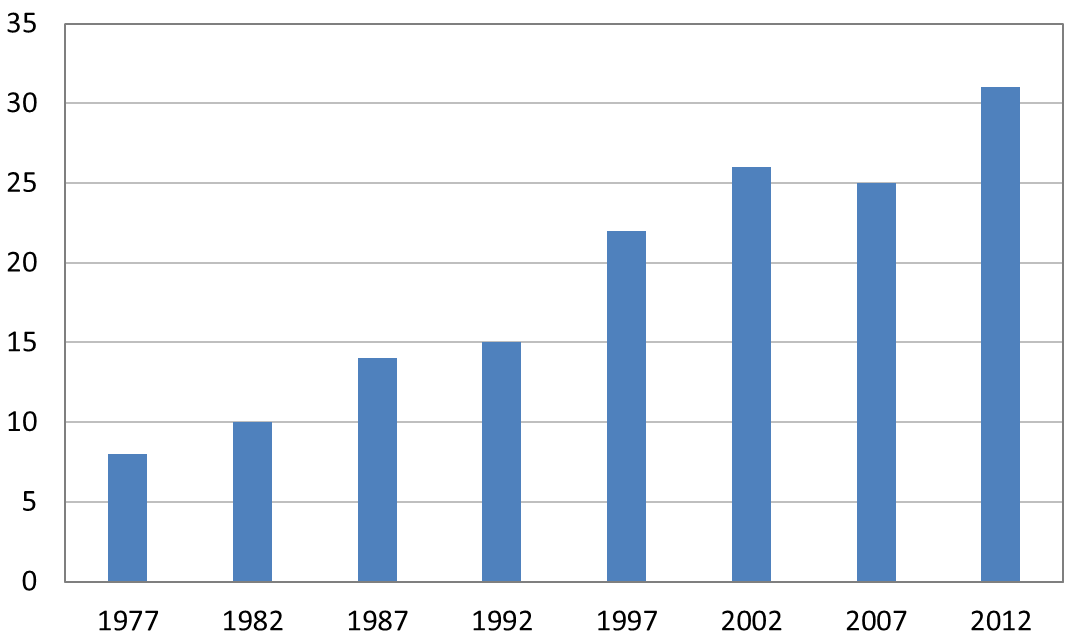

Another world record PNG might hold is the number of candidates per seat. The report has a fascinating table, graphed here, showing the steady rise in the number of election candidates per seat since 1977.

Average number of candidates per seat

Finally, the evaluation points to problems with seat sizes. The average seat in the 2012 elections had 53,700 registered voters, but the largest (Laigip-Porgera Open) had 122,202 registered voters, and the smallest (Rabaul Open) only 22,403. The report informs us that “Parliament has systematically rejected all proposals made by the PNG Boundaries Commission to redress present inequalities, without legislating alternative approaches that might solve the problem.” (p.15)

The evaluation also makes a number of interesting observations about the effectiveness (or otherwise) of Australian assistance. This assistance has come in two forms: longer-term capacity building and short-term, focused efforts every five years to help run the elections. The evaluation finds that there have been some improvements over the last decade in the capacity of the PNG Electoral Commission (PNGEC) but that these are “not commensurate with the effort invested.” (p. 28) And the two types of assistance were not well coordinated. At one point, close to the 2012 elections, there were advisors under the AusAID PNGEC capacity building project for gender and HIV/AIDS, for M&E (1.5 advisers in fact), and for corporate planning, but there was only one actual elections operations adviser (p. 32). It is telling, and an indictment, that the report is forced to recommend that “[a]ny future Australian electoral assistance to PNGEC should focus mainly on strengthening election delivery capacity.” (p. vi)

There is a lot in this evaluation for both governments to reflect and act on before the next round of PNG elections in 2017. The Coalition might have decided that Australia won’t be distributing text books or drugs in PNG since these are “the responsibility of sovereign governments,” but there is no suggestion that we won’t be working with PNG to deliver the next election, even though it is hard to imagine any government responsibility more core than the holding of elections.

We’ve been critical of late of a number of evaluations coming out of DFAT and its Office of Development Effectiveness. This evaluation shows just how useful they can be. Credit to its authors, Simon Henderson and Horacio Boneo.

Stephen Howes is Director of the Development Policy Centre.

This piece from Bomai D Witne provides an interesting addition to this discussion in terms of how money politics plays out in communities and strategies employed by (aspirant) candidates and electors in order to participate to (perceived) best effect: http://asopa.typepad.com/asopa_people/2014/05/the-wiles-guiles-of-national-election-campaigns-in-png.html

To be fair to PNG, the terrain and communications systems are a significant factor when elections are being undertaken. In addition, costly security arrangements, where the police and armed services have to be called out to maintain law and order must also account for the increased expense of holding elections. Disputed returns and stolen ballot boxes have dogged recent elections and caused extra costs.

A corollary of the excessive election costs however is that these considerations as well as other factors cause PNG to only holds elections every five years. That means that whoever is elected has five years to cement his/her grip on the available funding and funding sources. It also means that each electorate is stuck with their MP even if the MP proves ineffective, just disappears into the flesh pots of Moresby or travels overseas and never turns up at home except with ‘gifts’ immediately before an election.

Australia made a mistake in instituting a Westminster system of government albeit under external pressure from the UN and many new African states that have since descended into civil war and chaos. Distant authorities from the UN also presumed that everyone should logically replicate the rapid British evacuation of African colonies.

The quantum leap between the traditional PNG society and a modern westernised nation was clearly impossible given the limited time available to train responsible PNG officials and politicians at the time. Younger, educated PNG politicians may well now want to change the current system but are meeting strong resistance from those who have assumed power and won’t give it up easily.

The dilemma Australia faces is that any aid will logically only help those who currently want funding to manage the programs to suit themselves. Why change the electoral system when it works for those in power?

With the benefit of hindsight, the PNG Parliament should have had some form of review facility or even an upper house elected by each District and now Provence. Provincial governors cannot perform a review function if they are included in the lower house political power games.

An upper house made up of Provincial Governors who could reject legislation and return it to the lower house would help ensure no regional block or alliance takes control on the Parliament.

Alas, who in the PNG government would now be prepared to push for a change to the Constitution to allow this to happen?

Agree that a “cooling saucer” would be a nice tool to have in parliament…..talking about world records in PNG we can pass bills at the speed of light.

Would be good to put a brake on this exuberance……….

What Paul Oates describes sums up what transpired in PNG elections these days. What I want to add to is the cultural expectation of ‘reciprocity’ that underpins the ‘big man’ system is the fundamental cause of corruption and manipulation of the voting system. As candidates sought to gain access to national wealth, power and glory from becoming a Member of Parliament, vote buying, multiple voting schemes, bribes and even threats are used to gain votes. Block votes are common as there is an unwritten contract between the tribal candidate and the tribe the candidate is representing in the contest. It is an unwritten social contract between the candidate and the tribe that once the candidate wins, wealth, power, dominance, and glory will flow to the candidate and the tribe in return. From this perspective once the candidate wins the seat, he/she immediately seeks to align with the highest bidder so the buying of votes to form government intensifies. Corruption does not only involve the buying of votes in the electorates but intensifies after the election when factions start to ‘horse trade’ to form government. It does not help when voters start to put pressure on the candidate to provide personal wealth and expected community needs, thus, spurs on more demand for the candidate to seek funding through legal and illegal means. The whole electoral process is corrupted because of the cultural expectation of ‘reciprocity’ expected of a ‘wantok’. These underlying value of ‘reciprocity’ is the cause for the spiral election costs which will get even worse as population increases, poverty sets in, expectations increases, failure of public service to deliver, MPs duplicating work of public servants to bring services more efficiently, and ‘horse trading’ intensifies to form coalitions in a fragmented political environment.

How can a country with a population of 7.2 million (UN 2012) spend $US207 million on elections. Such spending is extravagantly ridiculous. The huge spending on elections could be reduced drastically, and the money used to assist in getting the poor out of poverty. It is about time that the Australian Government and other donors redefine how their funding should be spent on poverty reduction intervention as opposed to the supporting astronomical spending on elections.

I agree with Tom for the access in funding of elections in PNG, except that the Australian Government is very much obsessed with the illusion security threat to Australia if PNG elections ever failed. In such a scenario, it believed the instability could eventually lead PNG’s fragile political situation to a ‘failed’ state. In this context, the spending of Australian taxpayers’ money is justified but the actual situation could be otherwise different? Australia and PNG are geographically connected but their international relationship is far from being cordial. Just look at Australia’s immigration policy towards PNG citizens, its incredible how its almost impossible for a PNG national to just get on a plane and pass through Australia to other countries, as a first point of entry. Doesn’t that portray what is deep rooted in the Australian Government’s mind-set that PNG is posing serious security threat to Australia and its people, and therefore it needs to spend more money to uphold democracy in that country, whether it is ridiculous makes no difference to Canberra. The question is not of when it will stop funding elections (whether in kind or in cash) in PNG but what is the saturating point of which spending could be reduced, assuming that the notion of security threat remains unchanged as it was ten years ago.

The growing disparity of comparative electoral costs between PNG and other nations simply reflects the differing objectives being sought by the various candidates in each country.

In today’s PNG, the ultimate goal is to become a politician. This achievement equates to endless power, cash to spend as you wish and prestige. In Australia and many other western countries, politicians are mostly held in very low regard and reputedly, just above or equal to ‘ladies of the night’.

Some of the reasons for this disparity of views are as follows:

PNG people will mostly vote along tribal grounds and allegiances. Even though a politician might be reviled and not trusted, voters will still not trust an outsider. Mind you, something similar often seems to happen in many rural shires in Australia these days.

Given the poor or non existent media reporting and public knowledge of how corruption has been allowed to flourish, PNG politicians often seem to get away with corrupt practices and never be held accountable. People complain about corruption but still support their leaders who secretly condone such practices as it allows them to become and stay as MP’s. Some younger and more ethical MP’s are trying to reverse this trend however they are very much in the minority at the moment.

In a general sense, the ultimate goal in traditional PNG is to become the equivalent of a ‘big man’. A big man in the traditional sense distributes wealth and so gains power from those who benefit from the wealth distribution.

The only way to obtain the position of a ‘big man’ in today’s PNG is to aspire to become a politician. Since political parties come and go, ethnicity becomes the essential ingredient to building a voter base in most rural electorates in PNG.

In countries like the US and Australia where voter blocs are uncommon, political parties attempt to appeal to a poorly defined voter class system called erroneously the ‘The Workers’ or ‘The Middle Class’. In essence Australian governments are not won but essentially lost when the ‘swinging 10 -15% of unaligned voters actually decide the results.

In PNG, voters end up with a bewildering number of candidates all trying to gain votes by ‘whatever means’ but essentially still within an ethnic voting bloc. That’s possibly one reason why large electorate are still allowed to exist.

Various alternatives have been tried to improve the PNG electoral system however any system will only have the same basic level of integrity of those who control it.