The Papua New Guinea Department of Health collects routine health information through its National Health Information System (NHIS; now often referred to as eNHIS). The system is set up to gather highly and ever-more detailed monthly reports from over 800 health facilities (sub-health centres and higher) on a wide variety of conditions. In some provinces, data entry on tablets has now been introduced at the health facility level with the aim to improve the timeliness and accuracy of health statistics.

In this two-part blog, I explore the history of PNG’s health information system, and both show and explain why it may currently be too complex and extensive. I conclude with some thoughts on the way forward. This case study, with a particular focus on one country and one disease (malaria), holds many lessons for other countries.

Some of the earliest systematic health records from PNG date back to the visit of famous German microbiologist Robert Koch, who not only identified mycobacteria as a causative agent of tuberculosis but also conducted malaria surveys in the area of present-day Madang in 1900. The Australian administration subsequently gathered data from across the country for its program managers at the national level. After independence, and particularly after the decentralisation of health services to the provinces in 1983, efforts were made to strengthen and even computerise the health information system but the decentralisation limited the control of national managers over the provincial systems. Differences started emerging between the provincial systems leading to a situation where “any uniformity in systems appeared to be due to several provinces ordering their stationery from the same printing company, which provided a limited range of forms in its catalogue”. The situation changed after 1995 when, following a review of existing systems, a unified health facility reporting system based on modest adaptations was rolled out across the country.

This first standardised health information system included a single form for monthly reporting of key indicators. It was meant to reduce the reporting burden on health facilities and make it easier for provincial and national level staff to compile and analyse data. It combined the key features of seven or more forms previously in use. A folded A3 paper remains even today as the format of the monthly summary reporting tool of the PNG NHIS.

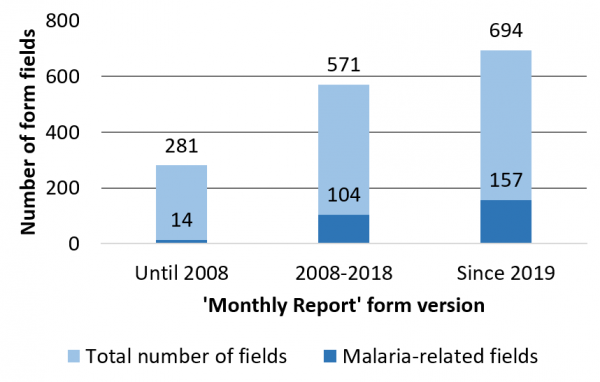

Yet, while the size of the paper has remained unchanged, the amount of information collected on the form has increased several times. More and more recording fields were added to increase the level of detail and extend the number of indicators. Reporting of malaria cases and malaria-related indicators is probably the most extreme example of how the ‘Monthly Report’ was extended over time.

Over the course of three revisions of the ‘Monthly Report’ form, the number of fields related to malaria increased from 17 fields until 2008 to 104 fields in the period 2009–2018 to 157 fields in the newest version in use since 2019 (Figure 1). In total, the latest version of the form has almost 700 data fields to fill each month – each from 800 health facilities!

The malaria-related fields added over time increased the disaggregation of data, for example, into sex and age groups, into presumptive (‘clinical’) diagnosis vs. confirmed diagnosis (by rapid diagnostic test or microscopy), adding Plasmodium species composition for both diagnostic methods, details on the number of administered doses of artemisinin-based combination therapy, eventually even linked to the underlying method of diagnosis.

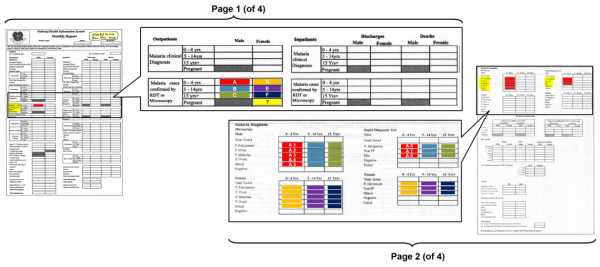

To complete the ‘Monthly Report’ form, health workers have to collate an increasing amount of data at the end of each month from tally sheets and the recently introduced ‘Malaria Register’. At the same time as the number of fields in the ‘Monthly Report’ form increased, it also became more complicated to fill, requiring the adding-up of several fields from one page to fill a summary field on another page of the same form.

For example, in the latest version, as shown in Figure 2, the total monthly number of outpatients in the category ‘Malaria cases confirmed by RDT or microscopy, males, 0–4 years of age’ (field ‘A’ shaded in red on page 1) is the sum of eight fields (A1–A8 shaded in red on page 2). (Fields A1 to A8 are filled by adding up tallies from a daily tally sheet, which itself is based on the ‘Malaria Register’ with individual patient records.) This has to be repeated five more times for other sex and age group combinations before repeating it six more times for the category ‘Malaria clinical diagnosis’. Every month. Only the field for pregnant women on page 1 does not require any adding up because there is no corresponding field on page 2.

Is all this additional information needed, and is it used? The short answer to both questions is no. Of course, more detailed data is essential to target interventions when case numbers are very low. In a malaria elimination setting, real-time individual case-based reporting is required to trigger case-based investigations. Yet, while the national malaria control program is likely to adjust its activities in the coming years from a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach to a more targeted approach, hardly any place in PNG is close to malaria elimination or has the capacity to implement case-based investigations and response action. Hence, the programmatic adjustments are unlikely to require the level of detail currently found in the NHIS malaria data.

There is also little evidence that the increase in the amount and detail of routine malaria data has changed the direction or implementation of the PNG malaria program over the past years. And in the annual health sector review documents, the same bar charts of aggregated malaria case numbers are presented every year.

Basic NHIS malaria indicators (e.g. incidence by district) and survey results are taken into consideration when scheduling national interventions, for example, bednet distribution rounds. But, while a 2019 Health System Review found that “there is increasing use of the data at the provincial and district levels for planning and setting targets”, several malaria program reviews (e.g. in 2016 and 2019) found little evidence of malaria data being used for decision-making at the sub-national level. For example, despite half a page of the ‘Monthly Report’ being dedicated to medicine shortages, the collection of the data did not prevent (or lead to rapid mitigation of) large-scale antimalarial drug stock-outs observed in previous years.

In part two, I explore the reasons the data is not used, ask why it is collected nevertheless, and discuss what can be done to improve the situation.

Dear Dr. Hetzel,

As the Secretary for the National Department of Health of Papua New Guinea, I wish to respond to the two opinion pieces published by Dr Manuel Hetzel of the Institute of Medical Research in the Devpolicy Blog.

The criticisms of the National Department of Health’s (NDoH) National Health Information System are factually incorrect, and are not supportive of our progress with health system transformation through improved performance monitoring. Such criticisms and lack of meaningful engagement erode the strides we are making in improving the timeliness, accuracy, usefulness and impact of the nation’s health data systems. We share an expectation that foreign consultants do not undermine our national efforts to develop and build world-class data systems.

Dr Hetzel states that “most importantly, a health information system must be owned locally and designed in a way that is consistent with the country’s capacity to operate it and utilise the data for improved programmatic decision-making.” The electronic National Health Information System (eNHIS) is nationally owned by the NDoH and replaces a moribund system running on non-supported software that we have had in the country for decades.

Given Dr Hetzel and colleagues at the Institute of Medical Research have access to the NDoH’s more than 1 million suspected malaria patient testing records, geo-located to one of more than 20,000 villages and urban settlements, I would encourage Dr Hetzel and colleagues to reflect on their role as malaria researchers and to use these data to better support the country with more meaningful contributions.

Dr Hetzel’s statement that health workers need to collate “an increasing amount of data at the end of each month from tally sheets and the recently introduced ‘Malaria Register’” is factually incorrect, entirely misses the point of our data transformation over the past 5 years and highlights his lack of understanding of and engagement with our national health data systems.

To be very clear, the NDoH’s eNHIS malaria testing register contains 13 clinical and demographic fields that are then used to automatically generate the indicators required to monitor malaria and manage the program – collation does not fall on the health worker and they are certainly not required to complete both. Innumerable malaria indicators can be automatically generated from the existing data capture, so the commentary around WHO and Global Fund requirements for malaria indicators creating a burden is simply not true. Fortunately, we have overcome the previous challenge of ensuring that Global Fund supported malaria partners cease to send our national malaria data offshore for entry into systems outside our national health information system, which effectively paralysed the capacity for national malaria monitoring.

Dr Hetzel claims, “ls all this additional information needed, and is it used? The short answer to both questions is no.”

The department does not subscribe to Dr Hetzel’s logic that if programs are weak, what is the use of data? “…[D]espite half a page of the ‘Monthly Report’ being dedicated to medicine shortages, the collection of the data did not prevent (or lead to rapid mitigation of) large-scale antimalarial drug stock-outs observed in previous years.” I believe that any weaknesses in medical supplies systems does not mean that medical supplies data are not important – to the contrary, it is with better data that well managed programs can make greater impact. The important steps taken by the proactive use of technology to enable the government to make data-evidenced solutions is our national objective.

A recent National Malaria Program Review for the development of the new National Malaria Strategic Plan, concluded that eNHIS contains all the information a province or district needs to run a successful malaria program. Dr Hetzel was part of this team. While we acknowledge the system is not being used to its potential, we are actively engaging with the provinces to make better use of their data for monitoring, evaluations, and reactive planning. The innovative approach of mobile tablet data entry we are implementing enables automated feedback on performance for all reporting health facilities every single month – never previously achieved and not achievable in the Papua New Guinea context without electronic data systems at facility level. Further, the eNHIS has been enabling data quality checks upon data entry to improve data quality at the periphery. As part of the nation-wide rollout, the tablets have been deployed to 1/3 of health facilities in the country. Unfortunately, COVID-19 has disrupted the expansion which will continue in the near future to the remainder of the provinces to be completed in 2021.

We expect the modernised NHIS to use the existing geo-coded national household and village datasets to better utilise the NDoH’s capacity for planning, monitoring and evaluating bed net distribution campaigns, monitor spray programs, and track individual case follow ups.

I would encourage Dr Hetzel and colleagues to have greater engagement with the health data landscape in Papua New Guinea and all of its stakeholders and to identify how a greater contribution can be made than undue critiques that do not portray the efforts made by the NDoH in the last 5 years to modernise the NHIS.

As a nation, we require credible agencies to assist us with using our NHIS to tell us, for example:

* How can data on treatment administered be used to monitor and enable the most rational use of anti-malarial drugs?

* How can data on malaria-negative patients from the malaria testing register be optimised for detection of outbreaks of (non-malaria) febrile illness and actually be monitored by local authorities?

There are many more public health issues we can solve with data.

With health data systems that can now tell us what facilities are open, about the nature of their service delivery and who from public health programs is logging in and using the data (including your malaria program counterparts), we have the nationally owned tools that we as the national health authority consider appropriate for our context. This is further evidenced by the assistance of both Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade and the Asian Development Bank that have been supportive of our efforts over many years.

We look forward to a more meaningful dialogue going forward.

Yours Sincerely,

DR. PAISON DAKULALA

Acting Secretary