The just-released AusAID’s Management of Tertiary Training Assistance is the Australian National Audit Office’s (ANAO) first audit of the aid program since 2009. Focusing on scholarships, it fills a big gap in the Australian aid literature.

The effectiveness of scholarships is impossible to evaluate. How much more of a contribution do individuals make to their country’s development once they obtain an Australian scholarship? We really have no idea, and we never will.

There are a few preliminary checks that can be made, mainly through tracer studies. If individuals educated through scholarships are unemployed, have been demoted, or have gone overseas, questions start to be raised about effectiveness. Even then, as Ron Duncan has recently argued (in an exchange on this blog) one or two well-educated individuals can go on to make a huge difference, and make a largely unimpressive scholarship program worthwhile.

Given these difficulties, one wouldn’t expect the ANAO audit to have the final word on whether Australian scholarships work or not. It does, however, provide a number of fascinating and important insights. Here are four. There is a fifth, about migration, which I’ll save for another day.

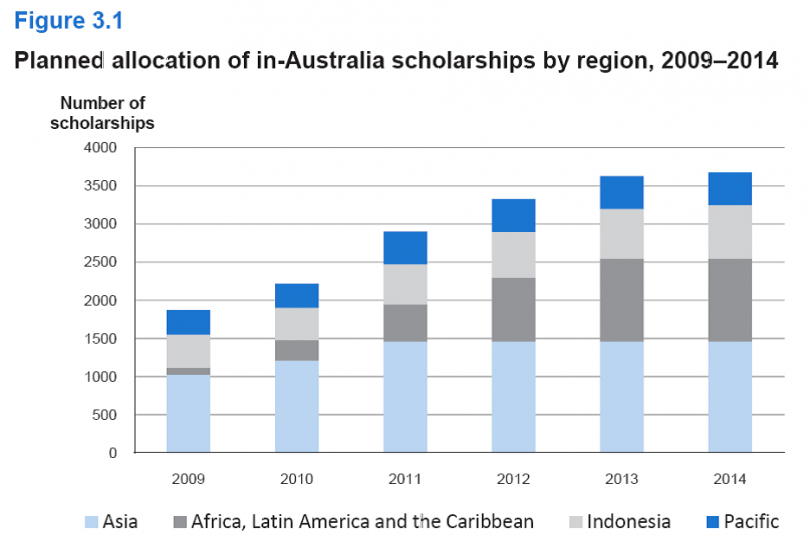

The first thing the ANAO audit makes clear is the rapid recent and projected growth in scholarships. Between 1995 and 2000, the number of new scholarships to study in Australia halved from 2,000 to 1,000. It stayed at this level until 2005. Now scholarships are back up to 2,000, and by 2014 they will reach almost 4,000. So scholarships are back in fashion, big time.

My guess is that under Foreign Minister Downer’s leadership, with his emphasis on governance and in the context of a stagnant aid budget, scholarships got squeezed out post-1995. But the scaling-up of the aid program, begun early last decade, expanded the room for scholarship spending, something the 2006 White Paper was sympathetic to. The changing mood was evident in November 2005 when Prime Minister Howard went to Pakistan and announced 500 new scholarships.

The second interesting piece of analysis is the distribution of scholarships. Figure 3.1 of the audit shows that more than half of the projected increase in scholarships will go to Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean. Scholarships for these regions are expected to rise from virtually zero in 2009 to over 1,000 in 2014. So, whether or not we will have a global aid program, we are clearly moving to a global scholarship program.

Third, as the title suggest, the audit goes beyond scholarships to look at the tertiary sector more broadly, especially in PNG and the Pacific. The ANAO audit provides strong backing for the University of the South Pacific (USP), and for Australia’s modest support for it. It notes that it costs about half as much to send a student to USP (based in Fiji) as it does to send them to Australia. Unfortunately, Australia’s support for domestic tertiary systems (in recipient countries) has fallen drastically world wide (see Figure 4.1 of the audit) and only remained steady (and low) in the Pacific (Figure 4.2). The audit argues that institutions such as USP don’t provide the same quality education as available in Australia, but that their low costs and importance as institutions warrant more support (p. 83). This is a convincing argument.

In hindsight, more should have been done through the aid program over the years to support PNG’s secondary and tertiary education sector, the quality of which has deteriorated sharply. Whether aid can help turn around the quality of higher education in PNG now is unclear. The audit includes a brief discussion of the Garnaut-Namilau review of PNG universities. This review, commissioned by the Australian and PNG Prime Ministers in 2009, was completed by mid-2010, and has been widely discussed, including at a public conference at the ANU in 2010. The fact that this report still hasn’t been formally released suggests that it’s unlikely we’ll see a reform program for PNG’s universities get off the ground.

Perhaps the audit could have said more about whether a different approach to scholarships is needed for PNG and the Pacific. It highlights the findings of reviews from Solomon Islands and Kiribati that the increased number of scholarships and training opportunities for these countries is actually undermining government capacity by reducing further their already “limited human resource pool.” (p.71) It also notes that a substantial number of PNG scholarship holders struggle in Australia, and reports that 15% of returning scholars to PNG were either unemployed (12%) or had been demoted (3%). Perhaps in the Pacific and PNG there should be more emphasis on undergraduate or even secondary scholarships. This is an approach which Australia used to take, and which the not-for-profit PNG Sustainable Development Program is now trialling.

Finally, at least for this blog, the audit notes that AusAID “produces a large body of evaluative work, but very little of this is made available to the public” (p. 117). The audit counts some 30 evaluations and reviews that have been commissioned by AusAID on scholarships and tertiary training since 2005, but not subsequently published. Australia has signed up to the International Initiative on Aid Transparency, and this year’s budget made a big commitment to transparency. Some scholarship reviews and evaluations were recently made public by AusAID in response to a freedom of information request, and can be found here. But the ANAO’s trawl of unpublished evaluations is a good reminder both of the value of these audits and of the distance that is still to be travelled to make transparency a reality for Australia’s aid program.

Stephen Howes is Director of the Development Policy Centre at the Crawford School of Economics and Government, ANU.

Leave a Comment