Thomas Malthus is often trotted out as an example of an early, mean-spirited environmentalist. This has always struck me as strange: Malthus had no particular concern for the environment, he was a conservative political economist who saw burgeoning population growth as a reason to oppose helping the poor in England. Feed the poor, he argued, and they will breed more, which will ultimately make their lives worse. So, he reasoned, it was futile to help poorer people. In stating this, he was making a type of argument that has become commonplace among social scientists, particularly economists. He was appealing to the “law” of unintended consequences.

Thomas Malthus is often trotted out as an example of an early, mean-spirited environmentalist. This has always struck me as strange: Malthus had no particular concern for the environment, he was a conservative political economist who saw burgeoning population growth as a reason to oppose helping the poor in England. Feed the poor, he argued, and they will breed more, which will ultimately make their lives worse. So, he reasoned, it was futile to help poorer people. In stating this, he was making a type of argument that has become commonplace among social scientists, particularly economists. He was appealing to the “law” of unintended consequences.

Malthus’s original predictions, it turns out, were probably wrong. And some more recent attempts to oppose policy initiatives in the name of unintended consequences (opposition to seat belt laws, for example) have been preposterous. Yet the basic idea is sound: we live in a complex world, people aren’t easy to predict, and sometimes seemingly sensible changes go awry thanks to their unintended consequences. This is true in the comparatively easy world of domestic policy making. It’s also a problem that plagues the world of aid, argues Dirk-Jan Koch in his recent book, Foreign Aid and Its Unintended Consequences (free to download). As a result, even well-intended aid projects can go horribly wrong. Worse still, Koch contends, because evaluations often only study intended impacts, donors are sometimes oblivious to the unintended consequences of their work.

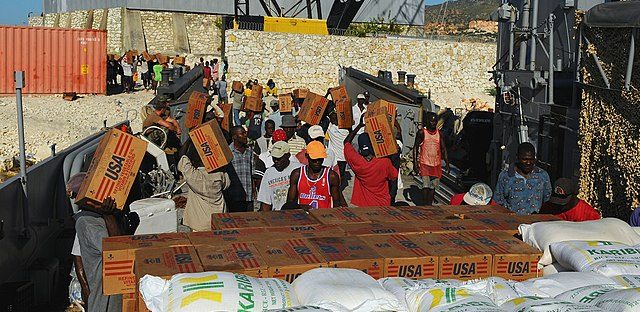

Koch won’t win any awards as a literary stylist but his book is clear and carefully laid out with a helpful taxonomy of different types of unintended consequences. He draws on an impressive range of academic research, as well as his own many experiences as an aid practitioner. He’s also even-handed: readers hoping for a feisty polemic that dismisses all aid as neocolonial or decries aid as pointless do-goodery will be disappointed. Koch describes many instances of aid’s negative unintended consequences ranging from a backlash against LGBTQI+ communities in Uganda after internationally supported campaigns for their rights, to the capture of aid by local elites. But he also discusses positive unintended consequences, such as deworming projects’ positive effects on education outcomes (to be fair these are contested). He also gives good examples of aid actors adapting their work to overcome problems: many aid donors no longer give food aid sourced from their own farmers; the World Bank has improved processes around its funding of large dams. The book is practical too: Koch offers suggestions for how aid organisations can tackle the issue of unintended consequences. He even gives advice on how evaluations can be undertaken with an eye for spotting them.

I’m not sure that all of the claimed unintended consequences described in the book really are unintended consequences. Some simply reflect the dilemmas aid workers face: should they feed refugees from a conflict knowing that as they do this they will also inadvertently be helping retreating rebel fighters? In the wake of brutal wars, the choices faced by those trying to pick up the pieces are often awful. That’s a consequence of war, not aid. Other problems Koch claims to be unintended consequences sound more like tradeoffs: if aid is used to fund an airport in Samoa (his example), it will increase greenhouse gas emissions but it will also (hopefully) provide people with better livelihoods. This has nothing to do with unintended consequences: costs have simply been weighed up against benefits, that’s all.

As a social scientist, I have my quibbles with Koch’s approach too: focusing solely on cases where unintended consequences occur (technically selecting on the dependent variable) allows him probe to the problem he wants to describe from many different angles. But it has the unintended consequence of making it seem as if unintended consequences are ubiquitous in the world of aid. Perhaps. But possibly most aid projects succeed, absent unintended consequences, or because the impact of any unintended consequences is small. Or maybe most aid projects fail simply because they’re so poorly conceived their intended consequences simply aren’t realised. Or perhaps donors are often distracted by other consequences, such as winning the New Cold War against China, and aren’t really trying to give aid that helps in the first place. Aid suffers many issues, and sometimes it succeeds. Readers would be wise not to read the book and conclude that unintended consequences are all there is to aid giving.

To his credit, Koch more or less acknowledges this limitation, and his case study analysis is vivid and useful nonetheless. He also provides more than enough evidence to convince me that unintended consequences need to be taken seriously in aid work.

Overall, Foreign Aid and Its Unintended Consequences, is a practical, sensible and readable book. Anyone striving to improve the world of aid should read it.

Disclosure

This research was undertaken with the support of The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. The views are those of the author only.

Unintended consequences indeed Terence.

Many moons ago as a fresh and clueless development assistance worker in country not particularly far, far away from here, I assisted a young man to grow fresh produce on his father’s land to raise money for school fees to continue his education. So far apparently so good.

The little project was a success, so much so that his mother, whose lot it was to till the land, became involved and turned it into a nice little family earner. Over the next year or so she raised enough to change the subsistence circumstances her family had laboured under for years.

The young man’s father, a chap called John, being a typically proud man from a strongly patrilineal society took most of the funds for himself. I was nonetheless quietly chuffed.

That was until his long-suffering wife came into my office looking fraught. Upon enquiry as to what was wrong, she told me she had destroyed all the vegetable produce in the field.

By now somewhat incredulous, I wanted to know why? Because came the reply, because John used the money I earned to buy a second wife.

Never quite forgot that unintended outcome.

Thank you Stephen,

That’s a great example of an individual unintended consequence.

Thanks again

Terence