There is no basis for the often-expressed belief that aid to the Least Developed Countries (LDCs) is, at this point, in decline. Nor for the same belief about aid to the transition countries—the 27 non-LDC countries that have graduated to middle-income country (MIC) status since 2000, other than China and India.

Previous posts in this series explored and refuted these two dogmas. In this concluding post, I suggest that the priority at this point is not to compensate for actual aid loss but rather to establish sensible allocation targets, at the global level, to help insure against future aid loss and promote aid growth for both these groups of countries.

All praise to the uber-allocator

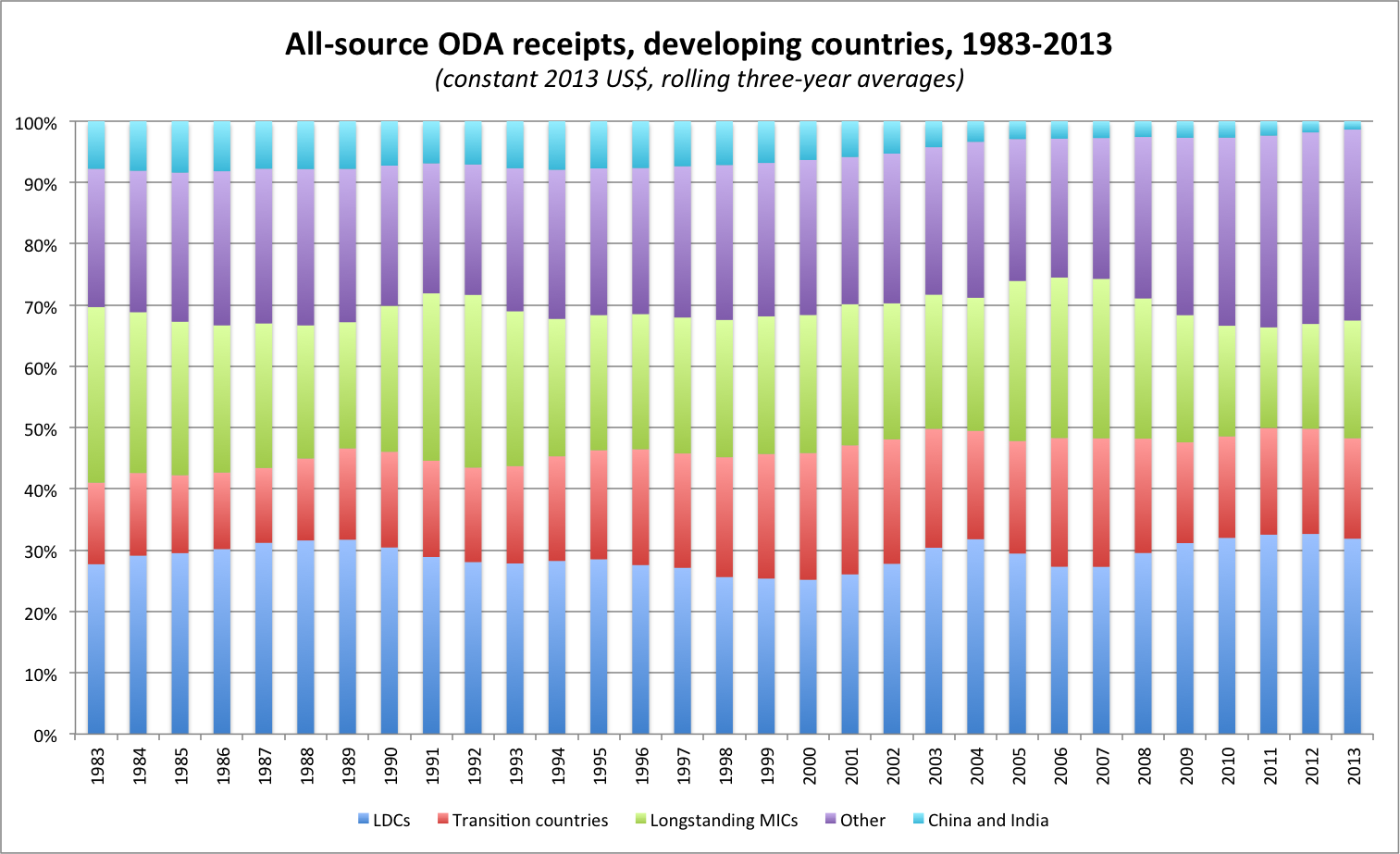

In the years since 2000, the global aid allocation pattern has changed in ways that are intuitively desirable—somewhat as if a wise and omnipotent aid uber-allocator had been at work (figure below). The 75-odd countries that are now LDCs and transition countries have for the past decade consistently received about half of all country-attributed aid, up from about 40% in the 1980s. Aid to China and India has diminished in relative as well as absolute terms since the late 1990s. Aid to the LDCs has grown substantially in relative as well as absolute terms since 2000. Aid to the transition countries, which has grown in absolute terms, has diminished very slightly in relative terms but has basically remained stable.

Aid to the longstanding MICs, while arguably too high and subject to fluctuations caused by debt relief (especially for Egypt and Iraq), has been somewhat squeezed in relative terms over the long term, and now stands at about 20% of all aid. Bilateral aid not attributed to particular countries—which includes aid accessed through bilateral donors’ regional and global programs (not to be confused with aid accessed through multilateral channels)—has grown to more than 30% of all aid received by developing countries. As the reasons for this latter change—aside from the growth in spending on domestic refugee and asylum seeker costs—are unclear, it is hard to judge whether the uber-allocator has acted wisely here.

Why the dogmas?

Why did the two dogmas discussed in this series gain currency? Perhaps they are in the same category as statements like, ‘no fragile state has ever achieved a single Millennium Development Goal’. The dogmas sound plausible, and striking, and lend vividness—a country face—to the argument that more aid is needed. And of course they could well become true, quite soon. It is reasonable to bet that global aid reached a peak or a plateau in 2013 and 2014 (aid in 2014 was a little higher than in 2013 in nominal terms and a little lower in real terms). Likewise, there is reason to believe, from the information presented in this series, that aid to the LDCs and transition countries might be in the process of leveling off, even if it has not actually been declining.

Whatever the reason for the dogmas, the need now is not to ‘compensate’ for lost aid, but rather to ensure that aid to the LDCs grows or at least does not decline, and that aid to the transition countries declines only gradually and in tandem with increases in the availability of non-concessional lending or tax-derived sources of financing for public investment. The question, then, is how to insure the overall gains made in the 2000-2013 period so as to guard against two rather opposed potentials: one a creeping mercantilism that would see aid increasingly allocated to export markets, the other a one-eyed ‘povertyism’ that would see aid increasingly confined to the specific localities where the sub-$1.25 per day consumers dwell.

ODA floors

Aid levels for the LDCs and transition countries cannot be insured by appeal to aspirational financing targets for the medium- to long-term—for example, ‘0.2% of donor GNI will be allocated to LDCs by 2030’ (EU), or ‘half of all aid should be allocated to LDCs’ (see here). A more meaningful and feasible commitment would be to place a floor under the real dollar value of per capita aid to both groups of countries at present levels. It would, at the same time, be prudent to place a floor under the two country groupings’ combined share of total aid, at the current level of about 50%.

At present, the approach just described would entail a floor of about US$50 per capita for the LDCs, whose collective GDP per capita is just over US$500. The consequent global commitment would be at least US$50 billion per annum with the current LDC population level. The actual level of assistance for a given LDC would of course vary as a loose function of various things, such as its distance from the median level of GDP per capita for the group as a whole and other factors such as smallness, remoteness, and so on.

The per capita aid floor for the transition countries, whose collective GDP per capita is about US$1,200, would be about $25, creating a global requirement of at least US$25 billion at the current transition country population level.[1] If total ODA were to fall below current levels, or if population growth and continued under-development were to take the LDC and transition country aid requirement well above US$75 billion, aid to the longstanding MICs, as well as bilateral aid not attributed to countries, would function as the balancing items.

As for the distribution of aid between the LDCs and transition countries, this would be to some extent self-regulating, in that improved living standards are correlated with lower population growth. Faster development in the LDCs and stagnation in transition countries (there are some signs of this) would lead with some degree of automaticity to a shift of resources toward the latter group. Alternatively, faster development in transition countries would lead to a faster tapering of their share of total aid.

There is no suggestion here of a mechanical resource allocation policy, or even one that might be applied by individual donor countries. The suggestion is rather that the world as a whole would do better to agree on per capita aid floors for the two ‘bottom billion’ groupings here discussed, combined with a floor under their combined share of total aid, than it would to fashion permeable commitments to fanciful long-term targets.

Promising, as the EU has done, to lift aid to 0.7% of GNI (0.2% for the LDCs) in the very year in which poverty is to be in some sense eliminated—that is, 2030—has something of Alice in Wonderland about it. By contrast, agreeing to strive for real per capita maintenance of aid to the two groups of countries that need it most would establish a presently meaningful, monitorable and achievable target, which would be a target for the collective of donors and particularly DAC donors, rather than necessarily for each and every donor. In addition, agreeing a global target for the transition countries would seem hardly less desirable than agreeing one for the LDCs, though to date targets have only been proposed for the latter grouping.

The underlying thought here, in case it is not obvious, is that it is worse for a country to be deprived of resources on which it already depends than it is for a country not to receive promised additional resources. There is no question that the level of aid currently provided to the LDCs, and perhaps also to transition countries, is very low in comparison to the cost of the public services needed by their citizens. It is likely that in many countries substantially higher levels of per capita aid would barely touch the sides. Nevertheless, the point of the present suggestion is to insure gains made and provide a solid foundation for increases if the environment becomes more conducive. In a more generous fiscal environment, the 50% floor under combined aid to the LDCs and transition countries would ensure that the existence of dollar floors did not become counterproductive.

Adopting broad targets of the kind proposed above for the purpose of monitoring the cumulative impact of a myriad of aid allocation decisions would go some little way toward replacing the wise and omnipotent aid uber-allocator who has recently been at work. She might not stick around.

Robin Davies is the Associate Director of the Development Policy Centre.

This is the fourth and final post in a series on development finance flows to least developed countries and transition countries. You can access all four posts here.

[1] Establishing a target of this kind would require placing some clearer boundaries around the category of ‘transition countries’, beyond simply the requirement to have graduated from low-income to middle-income status at some point since 2000. One option would be to add the requirement that countries be somewhere in the lower middle-income country per-capita income range, which is currently US$1,046 to US$4,125.

Hi Robin,

I’m all for getting rid of funding targets for 2030 but:

1. How would you see a collective target such as $50 pc working to motivate individual donors?

2. Also isn’t $50 pc a pretty stingy target, even as a floor? I know it is a slight step up from current total pc funding but what can be achieved with $50 pc total assistance especially after Western beneficiaries and administration have taken their cut and the $s have been spread across every donor’s favourite sector?

It seems to me that stepping stone targets at 5 year intervals and individual country accountability are both necessities for an effective donor target model.

On the stinginess point, yes, I agree the floor levels, especially for LDCs, are very unlikely to be adequate if treated literally as targets, even if one assumes maximum efficiency in delivery and a totally rational allocation of dollars to purposes. However, I think the aid volume risks are on the downside even if their realisation has been prematurely pronounced. A commitment to at least maintain per-capita aid at, or a bit above, current levels for these two groups of countries would have real bite, while not being so unrealistic that donors would find it necessary to post-date it to the year 3000. And it would not be incompatible with more traditional, medium- to long-term ODA/GNI target setting.

Part of what makes the aid floors idea relatively realistic is that it does not bind individual donors but only the collective. As you say, this might be thought to reduce its immediate motivational force for the average individual donor. But, by the same token, the collective nature of the commitment makes it easier to swallow, and it can subsequently be used to assess individual performance in terms of the contribution that a given donor is making to the satisfaction of the collective commitment. Also, there’s no reason why all contributions should be exactly equal, or rather proportional to GNI, because donors have different partner sets, and will sometimes be genuinely hard-up for a few years.

The idea is similar to that underlying the commitment to mobilise $100 billion per annum annually for climate change financing from 2020 on, except that in this case we are talking only about public money. A smaller example is the G20 commitment to maintain aid-for-trade funding at no less than 2011 levels.