Pacific island countries (PICs) are amongst the most profoundly affected by climate change. Some of these climate related challenges are existential, manifest in natural disasters, encroaching seas, and loss of arable lands. PICs are also uniquely interlocked in the testing of solutions.

Much rests on the quality of the responses to these challenges. Climate finance is a prominent feature of the international and national climate response, and has generated considerable expectation that it could offer a powerful remedy for the escalating climate crisis. This anticipation, however, is dying a slow death in the region.

The first sign that climate finance was not to be the saviour foreshadowed was the incredible difficulty PICs experienced, and are still experiencing, accessing the Green Climate Fund – climate finance’s flagship. When conducting fieldwork in Fiji and speaking to actors who should be the ideal destination of such funding, I was met with profound disillusionment at the abject failure of climate finance to trickle down to the national, subnational and local level.

While limited access to climate finance is in itself a serious and complex issue, we must also face another difficult truth. Climate finance alone will not meet the climate related adaptive and development needs of the Pacific. We must acknowledge that finance, once ‘committed’, must traverse an extremely complex landscape of challenges before positive outcomes can be realised. And the success of this journey, from dollar to outcome, is determined by sophisticated governance and regulatory arrangements in many different sectors and at many levels.

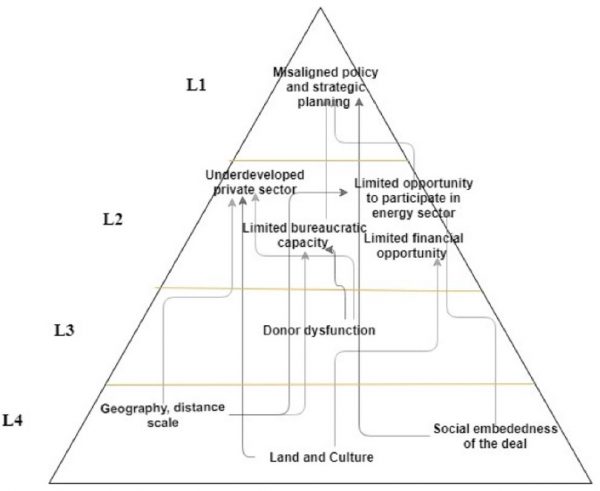

Barriers to various aspects of climate finance (such as the ability to scale up renewable energy) are often presented as discrete elements that exist in isolation. The framework below was developed from extensive consultations during our work in Fiji, which in its first phase aimed to scope barriers and opportunities of climate finance, and in its second (ongoing) develops governance and regulatory models for navigating barriers and embracing opportunity. This framework delivers a representation of barriers in which barriers: are entrenched and immovable to varying degrees (L1 –L4: least to most entrenched); and, like the people who try to surmount them, are relational.

What does this mean for climate finance governance?

It means that governors (those involved in ‘steering’ climate finance, including political leaders, non-governmental organisations, development partners, energy and financial sector regulators, investment fund managers, among others) must not only mobilise finance for climate related projects, but also steer it through a complex landscape of barriers. Further, governors that seek to ameliorate these barriers will likely have limited success if they focus on barriers in isolation.

To illustrate this point, let us take the barrier of legislation, regulation and policy that is misaligned to high-level goals of increasing renewable energy penetration in Fiji and its relationship to encouraging the participation of Independent Power Producers (IPPs). To resolve this seemingly tractable challenge you must simultaneously engage with issues that are more entrenched – such as, bureaucracies that may have various capacity constraints in implementing necessary reform, and entrenched interests in the energy sector, which have traditionally been self-regulating and may resist reform that threatens their monopoly. To illustrate a further level of complexity, the challenge of regulating an energy sector largely constituted by a dominant utility, is heightened by links with immovable barriers (see figure), of scale. Fiji, like most PICs has a small population – size poses a serious regulatory challenge, because regulatory capture is a real risk in small jurisdictions.

The implication of these barriers for climate investment in renewable and sustainable energy is that an uncertain policy environment heightens risk perhaps to an ‘unbankable’ degree. Such risk, contrary to popular practice, cannot be remedied by simply funding policy reform roadmaps that suggest more enabling conditions. Rather, as demonstrated by the complexity of the problem, it arguably additionally requires a strengthening of capacity in the public sector, partnership and support through to implementation of recommendations, and innovative approaches to regulatory challenges embodied in the energy sector.

This brief snapshot (for a fuller exploration of barriers in Fiji see study published here), hopefully highlights the following to the development community and climate finance governors more broadly.

- Climate finance alone will fall short. It must be coupled with national and subnational regulatory and governance reforms.

- Barriers to climate finance on a national level are relational, interlinking and complex.

- Thus, Barriers to effective climate finance governance cannot be viewed in isolation. They must be understood in terms of their various natures, but also most importantly, in terms of their relationships.

The importance of representing complexity has deep analytic roots in Fiji. As scholar Dr Sereima Nasilisili in her 2017 work exploring Important Knowledge in the community of Cu’u, ‘The indigenous approaches [in Fiji] examine problems in their entirety, together with their linkages and complexities.’ We need to draw on this wisdom as we seek to engage with existential challenges climate change presents our nearest neighbours and ourselves.

For more on climate finance and governance in the Asia Pacific please explore the newly launched Climate Finance Initiative Portal where you can access our team’s research, engagement and policy making tools.

Leave a Comment