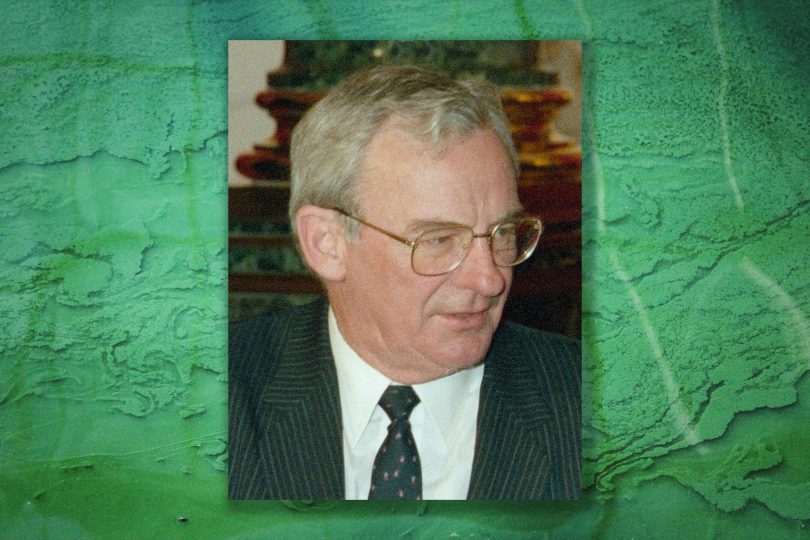

On the occasion of Bill Hayden’s state funeral, we thought it would be interesting to publish a few extracts from a chapter titled “Aid – A Two Way Process?” which Bill Hayden contributed to the book The Ethics of Development: the Pacific in the 21st Century edited by Susan Stratigos and Philip J. Hughes. The book was based on the proceedings of the 17th Waigani Seminar held at the University of Papua New Guinea from 7 to 12 September 1986. It’s not easy to find so we have extracted the full text of Hayden’s chapter.

Hayden served as Governor-General of Australia from 1989 to 1996. Earlier he was Minister for Social Security and later Treasurer under the Whitlam Labor government, leader of the federal opposition from 1977 to 1983 and Minister for Foreign Affairs and Trade from 1983 to 1988.

Somewhat sceptical about the effectiveness of official development assistance (ODA), Hayden commissioned the Jackson review of Australia’s foreign aid program in 1983, which led to increased professionalism in aid delivery.

During his tenure as Foreign Minister, Australian aid volume fell from its then peak of $3.6 billion (in today’s dollars) in 1984-85 to $2.9 billion in 1987-88, and did not climb back to its previous peak level for a decade. The Hawke government was cutting everything at that time (it was the recession before “the recession we had to have”) but Hayden probably wasn’t all that reluctant to see the budget trimmed.

In 1987, Hayden initiated the phasing out of budget support for PNG in favour of “program assistance” and moved to place Australia’s relationship with PNG on a more reciprocal basis.

In the extracts that follow, we see Hayden musing on the responsibilities of aid beneficiary countries towards both donor countries and other lower income countries; doubting the overall significance of aid for national economic development; expressing concern about the impact of budget support on initiative and self-reliance; contemplating a future in which the people of PNG no longer automatically look to Australia; and edging away from ODA/GNI ratio targeting in favour of “real growth” in the aid budget. It’s quite topical stuff.

Us and them

“Looking back over thirty years of the development debate, I see most starkly an ‘us’ and a ‘them’ division of the world into donors and recipients, which is obviously the product of history. We carry this historical baggage with us to our certain cost. The time has come to cast it off to our mutual advantage.” (Pages 51-52)

“… Development assistance is not a monopoly, any more than poverty or need is. For example, the countries of Melanesia, who have a wantok system Australians can only marvel at, already have a head start in their sense of common identity, their shared interests and their tradition of mutual support. Is not Papua New Guinea far better equipped than Australia, socially and culturally, to assist the Solomon islands after a cyclone?

Are not Papua New Guinea and Fiji more likely to have workable solutions to the problems of the small island economies than we can provide (for example by examining the complementarity of their markets)?

… Development is no longer a one way process from the rich to the poor. By turning it around to be a process of exchange between richer and poorer, it will have come of age to reflect the range of experiences and the realities of the later 20th century. As a responsibility shared by all sovereign states, aid for development is far more likely to find acceptance among all our constituencies. And as such it may even, eventually, have more chance of contributing towards that internationalism which ultimately eluded the framers of the United Nations Charter and all the political theorists who followed them.” (Page 56)

Governance and aid effectiveness

“It is interesting to note that most of the particular success stories of concessionary aid have occurred in agricultural programs. India, one of the largest recipients of agricultural aid from the World Bank, the International Development Association and the United States Agency for International Development, illustrates the point. In the early 1970s India was importing more than 10 million tons of grain each year. By the second half of the 1970s, she had become largely self-sufficient in food grains thanks to a combination of ‘green revolution’ technology, programs to improve marketing, agricultural credit for small farmers and irrigation.

But I want to emphasise that though concessionary aid played a significant role, the Indian Government played the major role, both in implementing the programs, and by improving policies relating to produce prices and the de-regulation of fertiliser distribution. Thus the institutional ability and political will of the country concerned appear to be among the most critical components of development success.

There is not enough evidence for us to draw categorical, sanguine conclusions about the effectiveness of concessionary aid in promoting the conditions for self-sustained growth or other forms of development in every situation. A cross-sectional sample of developing countries today reinforces the impression that aid is not, in itself, an important determinant of development. In some heavily aided countries growth has been slow, while in some of the more rapidly growing countries – Hong Kong, Brazil, Malaysia and Mexico – aid has been fairly unimportant; and in some countries, like China, not important at all. The elimination of mass poverty in rural China after the revolution of 1949 brought about sweeping social change, remains one of the most dramatic transformations in human history and was achieved almost without any foreign assistance. We therefore have to concede that in most cases, concessionary aid is a marginal input in the development process.” (Pages 52-53)

“… I have sought to emphasise that responsibility for effective aid lies also with those nations which receive it, and the success of development co-operation depends heavily upon the strength of the institutions, political will and administrative skills of developing countries. As the World Bank argues, it is domestic policies which hold the key to developing country performance.” (Page 58)

PNG-Australia relations

“… [W]hile other countries which receive aid from a range of donors have developed project planning and management capacity, Papua New Guinea, with substantial aid from a single source going direct into its budget revenue, has had little incentive to develop these capacities or to seek assistance from a wider field of donors. As early as 1978, a World Bank Report indicated that Papua New Guinea needed to re-orient its economy away from essentially Australian standards of investment, consumption and incomes, towards those more appropriate to, and within the long-term means of Papua New Guinea (World Bank, 1978). I suggest, moreover, Papua New Guinea is ultimately not well served by being buffered by Australia from some of the pressures of the world economy.” (Pages 56-57)

“Relations between sovereign states are a product of history, geography and economics, as well as strategic and other shared interests. For better or for worse, all these will forever make for robust relations between Papua New Guinea and Australia. Of course there will be strains as we explore new political and other interests or directions. We have to face the fact that a rising generation in Papua New Guinea will have a different perspective on the relationship from that of the people who have gone before them. This is also the case with younger Australians who have not witnessed Papua New Guinea’s evolution to independence and who consequently see Papua New Guinea as just another foreign country. This will call for careful management. I am confident that we can live and work together for as long as we each recognise that, at bottom, the foundation of so many of our shared interests is so solid.” (Page 58)

Aid volume

“As for our aid policy, I can only state that while the ratio of Australia’s aid to GNP will fall from 0.46% in 1985-86 to 0.39% in 1986-87, as a percentage of GNP it remains above the average for members of the Development Assistance Committee of the OECD. Looking ahead, the Government hopes that, as Australia’s economic situation improves, it will be possible to resume providing for real growth in our aid budget.” (Page 58)

Leave a Comment