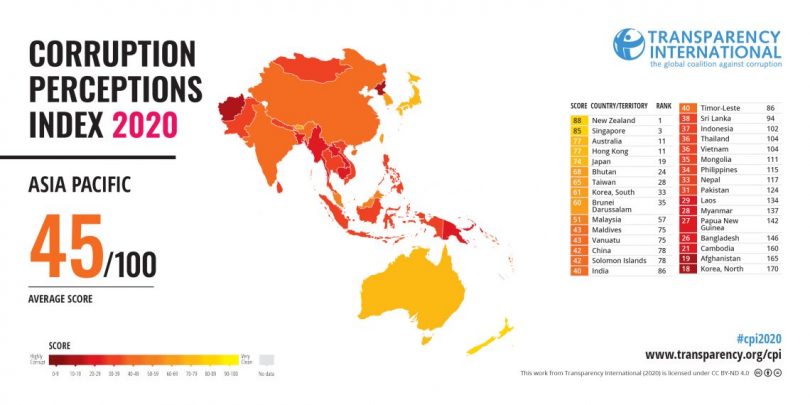

Transparency International recently released the 2020 annual Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI).

The CPI draws on up to 13 external data sources to give each country a score of 0 (very corrupt) to 100 (very clean). A country needs to appear in a minimum of three sources to be included in the report. Because of the limited data on governance available for the Pacific region, only three Pacific countries are included in the CPI: Vanuatu, Papua New Guinea (PNG) and Solomon Islands.

The CPI is the most widely used indicator of corruption worldwide. It is a powerful tool for governments and international institutions to understand and respond to corruption. It also helps international investors manage risks when entering a market. Pacific governments and other key stakeholders need to work with key institutions that collect such data so that more Pacific countries can be included. The more a country appears in various data sources that monitor different aspects of governance, the clearer the picture of corruption will be in that country.

CPI 2020 findings

New Zealand has a high score of 88 and for the second consecutive year is ranked number one on the index globally. Good governance translates into effective crisis management, and New Zealand has been lauded for its coronavirus response. The government has been open and transparent in its communication regarding the different measures in place to fight the spread of the virus. However, no country gets a perfect score and even here greater transparency is required for procurement related to the COVID-19 recovery.

Australia too scores highly at 77, although its score has lost eight points since 2012. This could be due to a perception that mechanisms to ensure strong oversight and accountability of public officeholders, particularly federal politicians, need to be strengthened. Key civil society groups have been calling for a national anti-corruption agency to be set up.

PNG, Solomon Islands and Vanuatu score 27, 42 and 43, respectively. These results have been largely stagnant. Solomon Islands and Vanuatu score the same as they did when they were first included in the CPI in 2016 and 2017. PNG’s score has averaged 27 since 2012. These results put Solomon Islands and Vanuatu in the top 50% of countries worldwide, but PNG in the bottom 20%.

Despite these low and stagnant scores, some bright spots exist where these countries have made substantial gains in building integrity.

PNG, after decades of tireless efforts from civil society groups, celebrated a victory in 2020 when legislation was passed to establish an Independent Anti-Corruption Commission. In Solomon Islands, the country appointed its first ever Director General to the national Anti-Corruption Commission. The priority now is recruiting and training staff to get the commission functioning. Vanuatu has held key high-profile political figures to account in the justice system with corruption charges.

The message from the 2020 CPI is that these successes will need to be sustained and supported for years to come before perceptions of corruption begin to improve.

At the regional level, Tonga joined the list of 13 other Pacific countries to have acceded to the United Nations Convention Against Corruption (UNCAC), the only legally binding universal anti-corruption instrument. Eleven Pacific leaders adopted the Teieniwa Vision against corruption in early 2020. However, wider endorsement amongst all the Pacific Islands Forum leaders is required for greater accountability and support to turn this vision into action.

Corruption during the COVID-19 response

2020 was a unique year in the Pacific because of the COVID-19 pandemic and two category five cyclones.

Governments took significant measures to respond to the pandemic in 2020. However, there was limited transparency and accountability in their responses. In Solomon Islands, there were allegations of diversion of emergency response funds by public servants, and in PNG, alleged procurement irregularities. Proper procurement process is important to avoid bribery, kickbacks and the misawarding of contracts. However, without adequate access to information, and sound oversight mechanisms, it is difficult to verify or disprove these claims.

Consequently, civil society actors and allies across all three Pacific countries in the index spent much of 2020 calling upon their governments to improve transparency and accountability in their responses to COVID-19. For example, in PNG, civil society demanded an audit of emergency funds and procurement.

However, civil society engagement has not always been welcome in all Pacific countries. Press freedom has also been a long-running concern. Under its state of emergency declared earlier in the year, Vanuatu ruled that media outlets could only publish stories about COVID-19 if they received official authorisation.

Access to information as well as space and support to facilitate meaningful civil society engagement needs to be provided for key reforms and response measures to have an impact. Key transparency and accountability mechanisms need to be strengthened and oversight institutions need to be made fully functional. This will require greater funding and support, and greater political will.

Drawing on experts and business leaders’ assessments of corruption in a country, the CPI can provide a strong evidence base for Pacific governments and civil society to work together in fulfilling their national anti-corruption commitments.

Without any high profile, or even low profile conviction, and the slow start of ICAC, how could there be a change in perception of corruption in PNG?