At the 2024 United Nations General Assembly, PNG’s Prime Minister James Marape said he wanted to make PNG a high-income economy by 2045. But this will not be easy. To improve living standards for its people and attain prosperity, PNG needs sustained economic growth. PNG has struggled to achieve this, despite its resource wealth.

The story has however been different for Malaysia. Within a single generation, Malaysia has transitioned to an upper middle-income economy and now the country is set to achieve high-income status between 2024 and 2028, after decades of relatively consistent economic growth in both aggregate and per capita terms (Figure 1). In contrast, PNG has stagnated at lower middle-income status since breaking away from Australia in 1975.

Implications for the respective societies’ welfare are evident. On average, Malaysians today live ten years longer, are five times more productive, and earn four times more. While less than 1% of Malaysia’s population lives below the poverty line, approximately 40% of PNG’s population lives in poverty.

What has driven this great divergence and disparity?

In some ways the two countries are quite similar. Both are resource-rich tropical countries in the Asia-Pacific region and former colonies of Great Britain, and in the 1960s both recorded levels of GDP per capita similar to PNG’s current level.

But two key features have set Malaysia apart from PNG. First, Malaysia has deliberately pursued and achieved economic diversification. Export diversification was one of the first measures Malaysia took after independence, following the Flying Geese model. Between 1980 and 2015, Malaysia reduced its reliance on primary sector commodities for exports from around 70% to below 20% and increased its share of exports in electronics and electrical appliances from 10% to 35%. The resources sector as a share of GDP has also declined over time to around 7% of the GDP in 2020. Today, the agriculture, forestry and fishing sectors no longer have the lion’s share in its economy.

In PNG’s case, the agriculture, forestry and fishing sectors, along with the minerals and energy extraction sectors, still dominate the economy. In fact, PNG’s resource dependence is actually getting worse. Resources as a proportion of GDP have over time increased, from around 10% in 1980 to close to 30% in recent years, making PNG one of the most resource-dependent economies in the world. Now, approximately 90% of total exports are from the resources sector. Manufacturing has never taken off. It contributed 4% to GDP in 1980s, reached a maximum of 5% in the early 1990s and slowly declined over the years to 3% in 2020.

The Herfindahl Hirschmann Index (HHI) in Figure 2 shows the stark difference between Malaysia and PNG in terms of export diversification. A HHI score approaching zero indicates greater diversity in exports, while a score heading towards one shows more concentrated exports. PNG’s exports have been becoming more concentrated over time, while Malaysia’s have become more diversified since the 2000s.

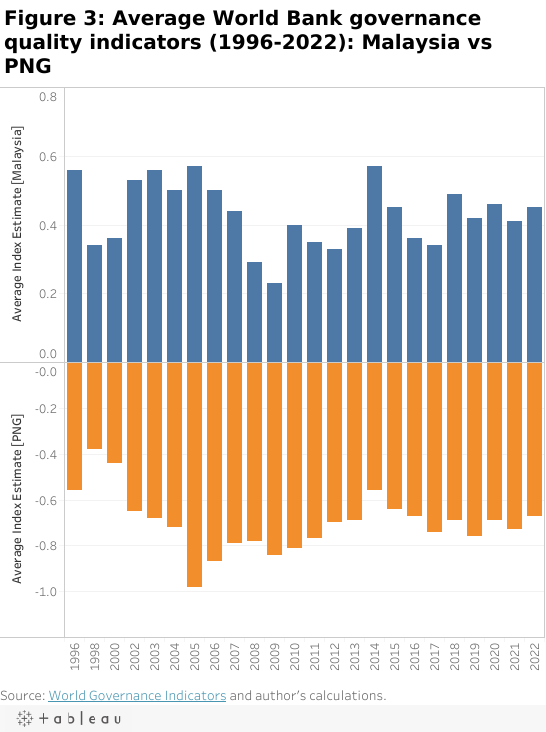

Second, Malaysia has stronger institutions and better governance systems. According to the World Bank’s governance quality indicators, which range from -2.5 (weak governance) to 2.5 (strong governance), the average quality of governance in PNG has been low over the past 25 years (Figure 3). In contrast, the institutions and governance indicators for Malaysia have been on average much higher over the same period, despite major corruption scandals and a long period of authoritarian democracy.

Why has PNG suffered from the “resource curse” and not Malaysia? Rents from natural resources are often wasted. They have been found to have a negative association with the control of corruption and effectiveness of governance. Further, the country’s entrenched clientelist democracy oils corruption. It incentivises politicians to focus on winning local political loyalty and securing votes at the expense of broader development goals such as investment in economic diversification.

Malaysia, on the other hand, has been mostly lauded for escaping the resource curse. Rents from its natural resources have been invested in infrastructure and human capital. In fact, Malaysia is one of the few countries that have followed Hartwick’s Rule, with investments equal to its resource rents.

It took Malaysia less than five years to transition from lower-middle income to upper-middle income status. However, it took almost 30 years of economic diversification policies and developing strong institutions to support its graduation to high-income status.

All the while, PNG has remained in the lower-middle income bracket. PNG should take heart from Malaysia’s experience that it is possible for resource-rich countries in the region to grow successfully and quickly with the right policies in place. But doing so will not be possible without economic diversification and better institutions.

Good article Kingtau. It is not rocket science to learn what you pointed out. It needs visionary leaders to drive the change. However, we can from Malaysia if we are to progress economically, socially and physically. Your article is much appreciated.

Thanks Mathew!

Excellent observations, Kingtau. While PNG shares similar fundamentals with Malaysia, such as collective culture, or being sensitive to social hierarchy, etc… we used these wrongly, I would think. We used our collective culture to reinforce or normalise things that are not serving our collective good – like corruption, or hatred towards a foreigner evading taxes disguising xenophobia, while we ignore our own big men misusing tax revenues. We also respect those in power even if they’re abusing that power. If only we understood the power of group thinking and aligned it in the right trajectory, we could have been somewhere ahead already.

Agree with you, Thomas.

Great comparative analysis! It is interesting to see value of the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index for PNG to be below the one for Malaysia in 1997. I am wondering what were the underlying factors and if some lessons from the past could still be relevant today.

Thanks Artemy. The normalised Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI), illustrated in Figure 2, is essentially calculated as the ratio of the difference between the sum of the squared shares of export and one divided by the number of sectors to the denominator, which is one minus one divided by the number of sectors in the economy contributing to export. So, in cases when the output shrinks, its captured in the first variable in the two differencing variables in the numerator of the index, so the total index falls when the number of sectors remains the same. That’s what happened to PNG.

In 1997, the PNG economy experienced a significant downturn due to the combined impact of frost, the El Nino-induced drought, and the Asian Financial Crisis, which saw a 6.3 percent contraction in output consequently affecting shares to exports. That eases the concentration in the primary sector, creating the illusion that export concentration is diversifying. Any lessons? Reducing output to make the economy look more diversified is not something everyone will be happy to pursue.

Excellent article, Kingtau. Important lessons for PNG government and policymakers to learn to turn the trajectory of socio-economic development of PNG around for the better.

Thanks Andy. Good to learn from them.