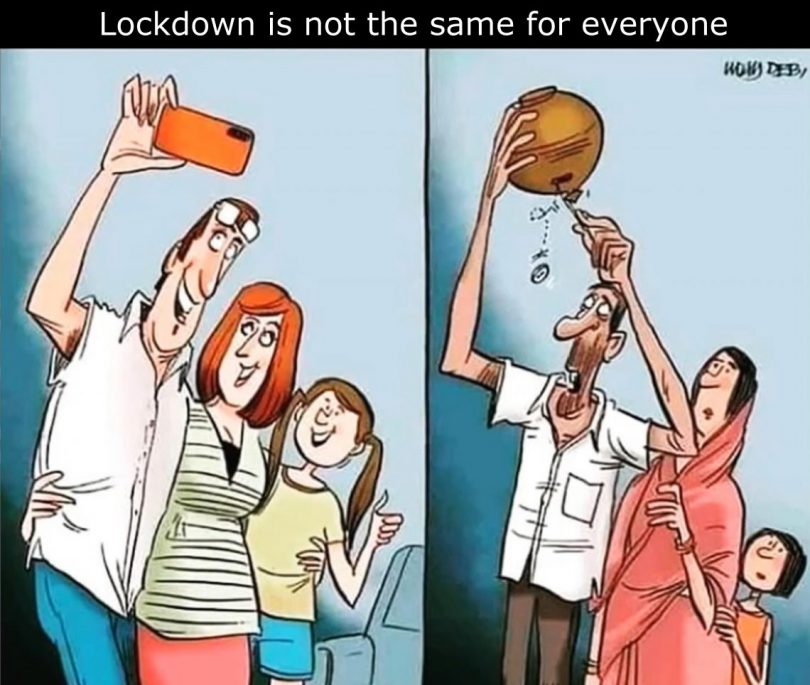

COVID-19 is impacting everyone. In Australia, declines in employment and incomes have resulted in approximately one-quarter of Australians indicating in April 2020 that they were finding it difficult or very difficult to live on their current income. Various policy and budgetary responses taken by the Australian Government have helped cushion the blow, including for low-income households.

Low-income and poor households across Asia have not been so fortunate. The economic and financial impacts flowing from lockdowns to curb the spread of COVID-19 have been severe in most Asian countries, with substantial declines in the incomes of people at the base of the economy, many of whom rely on microfinance to manage their household or microenterprise cash flows. A series of studies of microenterprise owners have shown average declines in income in Pakistan (85%), Bangladesh (75%), and India (70%). Migrant workers have also been hard hit, stifling the important flow of remittances.

Like all of us, people and enterprises at the base of the economy rely on financial products and services for basic needs such as savings deposits, receiving and sending payments, loans, etc. However, in developing and emerging economies such services are often only available from specialised providers such as microfinance institutions, cooperatives, NGOs, savings associations or self-help groups.

The Foundation for Development Cooperation (FDC) recently collaborated in conducting a survey in April with a coalition of 1,500 microfinance providers (MFPs) serving 130 million clients across 11 Asian countries ̶ the Banking with the Poor network. The survey aimed to identify conditions on the ground and opportunities for immediate and short-term mitigation of COVID-19 impacts on the microfinance industry and the clients it serves.

We found that the financial system and livelihoods of people at the base of the economy are in a precarious position.

Unlike previous natural disasters or financial crises, lockdowns to contain the COVID-19 outbreak have resulted in both a supply-side shock with people unable to go to work to supply or produce goods and services, and a demand-side shock with households and businesses unable to buy goods and services for extended periods. The combined shocks will likely result in a long-tail COVID-19 recovery.

This in turn is preventing microfinance providers from receiving repayments, making loans or accessing capital and liquidity from their funders. As a result, both the entire financial system and grassroots commerce are severely compromised. Lack of food and cash are the primary concerns across all 11 countries.

The FDC survey revealed that most (90%) households and microenterprises asked their MFP for a grace period or extension of their loan repayments. Surprisingly, few asked for partial or full debt cancellation.

Further, the survey showed that most (78%) microfinance clients mainly use and rely on cash because they don’t have access to, or hesitate using, digital or mobile money payments or deposits, notwithstanding the 4.4 billion mobile phone connections across Asia. With lockdowns, people reliant on cash cannot always access an ATM or money agent, and when they can, the queues risk compromising social distancing measures.

Government stimulus measures directly targeting the informal economy as at the end of April were limited. Most people at the base of the economy work or run microenterprises within the informal economy, which constitutes between 70 and 90% of the total employment and unincorporated businesses in most Asian countries. These people usually do not have access to social security or similar safety nets such as insurance, and are most likely to belong to poor households and/or microenterprises not covered by general COVID-19 stimulus packages, subsidies or other relief measures.

The survey showed that the stability of the financial system at the base of the 11 economies is compromised:

- Prolonged lockdowns (ability to earn income and make repayments) have lessened the benefit of monetary policy relief.

- Inconsistent policy measures are creating confusion and financial distress. In some countries not all MFPs have been designated as an essential service (Bangladesh); moratoria on repayments are not being mandated consistently across the financial system (India); and provincial governments are free to set their own essential service policy (Pakistan).

- There is a real prospect of widespread MFP insolvencies – the majority of MFPs consulted are experiencing significant, negative impacts on key financial measures such as current and debt/equity ratios, operating margins and percentage of portfolio at risk.

Stable and sustainable MFPs are essential to the hundreds of millions of households and enterprises at the base of the economy that rely on MFPs to make their deposits and savings, access loans or make and receive payments.

How can stakeholders mitigate these COVID-19 related impacts?

- Governments can assist by deeming microfinance providers as economic frontliners providing essential services; engaging with development partners to enable MFP clients to restart their enterprises after the lockdown with a low-cost risk-sharing loan facility; and ensuring women’s representation and client protection in all COVID-19 response planning and decision-making.

- Regulators and the Central Bank can assist by expanding COVID-19 liquidity facilities to MFPs, and ensuring any moratoria mandated for MFP clients extends to MFP creditors to ensure stability across the entire financial system.

- Development partners can assist by working with the microfinance investor community to contribute to risk-sharing facilities; providing microfinance-related technical support to governments and regulators; and including the microfinance sector when supporting government social assistance programs.

While COVID-19 has had a devastating impact on lives and livelihoods, it has also revealed important learnings:

- Governments are realising the value of MFPs’ extensive networks servicing some of the most vulnerable and unserved communities in rural and remote parts of the country, and their demonstrated ability to distribute COVID-19 awareness messaging and prevention guidelines as well as food and health supplies and other necessary provisions.

- Given the importance of contactless financial transactions and potential to lessen the reliance on cash, there is a renewed push for enhanced digital connectivity and economy and addressing the key challenges of sourcing capital for MFP investment in digital systems, adequacy of the supporting infrastructure, and the consumer and staff education path to scale.

- There is a growing recognition of the key intangible asset underpinning successful microfinance – the knowledge and infrastructure (organisational capital) developed by microfinance providers in successfully supporting households and enterprises at the base of the economy.

While there is a clear need for substantial stakeholder interventions, the pandemic has also sparked creative and nimble responses by MFPs themselves, including live ‘e-doctor’ services via Facebook, online education and vocational courses, and virtual food purchasing and distribution collectives.

Encouraging signs in the face of adversity.

This post is part of the #COVID-19 and international development series.

Thanks Abby for your enquiry. Much of the information in the survey is commercially sensitive, at least for the time being. We may be able to share it on FinDev Gateway at a later date and will advise at that time.

Thank you for this analysis. Do you have a publicly available report or publication of the survey results you mentioned? If you do, we’d be interested in sharing it on FinDev Gateway where we are maintaining a list different publications and data trackers on the impact of COVID-19 for financial inclusion.