Papua New Guinea (PNG) is often presented as a country with little hunger. The idea of “subsistence affluence” was developed in PNG in the 1970s to elucidate a situation in which people ate what they grew, and grew enough not to be hungry. That idea has persisted. Writing in 2007 on poverty in PNG, Diana Cammack reported the widespread view that in the rural areas of PNG “there is little hunger” (p.21). Some experts support the idea as well. In 2000, leading PNG agricultural expert Mike Bourke wrote that “Food security is generally good in modern PNG. This is because a high proportion of the population is engaged in subsistence agriculture; most people have access to land for food production; there is a diversity of subsistence food sources; and most people have access to cash income with which to buy food when subsistence supplies are inadequate” (p.6).

For a long time, however, the data has suggested that in fact hunger is widespread in PNG. As John Gibson worked out, the 1996 PNG Household Survey showed that “In both the urban and rural sectors, approximately 42 percent of the population are not meeting food energy requirements of 2000 calories per person per day”. The 2009 Household Income and Expenditure Survey produced similar results, as did a more recent survey of four lowland provinces.

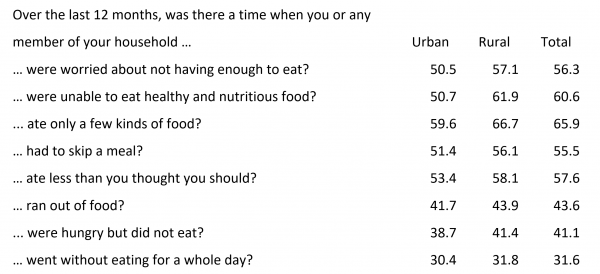

Now we have further evidence on the issue from PNG’s latest Demographic and Health Survey (DHS), collected between 2016 and 2018. Eight questions were asked about hunger, such as whether anyone in the household had been worried over the previous year about not having enough to eat, or had skipped a meal, or ate less than they wanted. The answers to these questions, shown below, certainly support the notion that there is widespread hunger in PNG. For example, 56% were worried at some time over the previous year about not having enough to eat. 44% ran out of food. 32% said they went for at least one whole day without eating.

Percentage of PNG households with various forms of food insecurity, by residence (2016-2018)

All the answers show little difference between urban and rural areas: hunger is slightly higher in rural areas, but evenly spread across both.

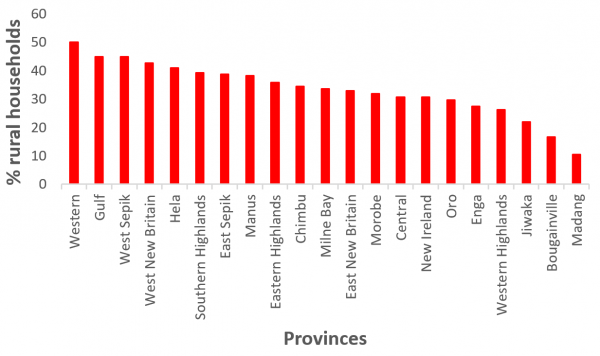

To explore further, we use the most stringent definition of hunger, that provided by the last question, namely that someone went without eating for a whole day. It is surely impossible to not eat for a whole day and not feel hungry. As mentioned, almost one-third of households said that they found themselves in this position at least once in the previous year.

There is certainly considerable variation across PNG. In the figure below we focus on rural PNG – where the great majority of the people live. Hunger is widespread. Even using this strict definition of not eating for a whole day, only three provinces (Madang, Bougainville and Jiwaka) have less than a quarter of their households hungry. Western Province has the most hunger among rural households with half the households hungry. Madang has the lowest with just over 10%.

Percentage of PNG households that went without eating for a whole day, by province (2016-2018)

One idea that is popular in explaining poverty in PNG is that it “is significantly located in the most isolated and environmentally disadvantaged parts of rural PNG” (p. 2). There are numerous lists of the most disadvantaged districts in PNG. We use that provided by the 2001 PNG Rural Development Handbook and, following convention, define the bottom 20 as the most disadvantaged. The DHS data is not presented by district, but we know that 9 of its 21 provinces have none of the 20 most disadvantaged districts. Of these, Bougainville, Western Highlands, New Ireland and Oro have below average levels of hunger, but the other five (Eastern Highlands, Manus, East Sepik, West New Britain and Gulf) have above average levels. Gulf is the second hungriest province by this measure.

In summary, hunger in PNG is not confined to urban areas nor to particular disadvantaged or isolated regions. Nor is the country’s nutrition challenge solely about improving the quality of diets, as important as that is. Many people are simply not eating enough. Perhaps subsistence affluence had an empirical basis in the past in PNG, but it certainly lacks one now. The DHS is the latest in a number of surveys to demonstrate that there is widespread hunger across Papua New Guinea.

Disclosure

This research was undertaken with the support of the ANU-UPNG Partnership, an initiative of the PNG-Australia Partnership. The views represent those of the authors only.

Pretty bold article. Is the intent to make government realise the situation (which they already know as they would have the survey results) or to agitate the people of PNG.

Anyways, good work.

The authors seem to have attempted to take one lone statistic from the PNG national statistical database and inflated it into a pseudo-scientific study that lacks credibility. I am not sure what is behind the motives but from experience there is usually a corporate interest involved. I do not know what that might be in this instance.

I guess many people would ask, is there a nutritional problem rather than a hunger problem? Certainly some 48 years ago balanced nutrition was the bigger problem.

The motive is to investigate the important question of whether hunger is widespread in PNG. There is a nutritional problem in PNG, but there is also evidence, in this blog and other surveys, that hunger is widespread.

Firstly, I would like to thank you both for your time spent in preparing the report. It was well presented and arguably an informative insight of the reality in PNG. We understand the motive of informing our government, aid agencies and the general public as a whole, of the concerning subject for possible intervention or any of that sort to alleviate the issue.

PNG has a totally different lifestyle; that’s the first thing to consider. Only the lazy goes hungry. The concern in all the comments I suppose, is the “Title” of your report. It is offensive to us citizens who work our lands and live moderate lives. I am certain the cluster sample collected by NSO was not a good representative of the whole population and questionnaires were not interpreted well by the respondents.

However, I see this report as a good indicator of PNG lacking the surveying skills in collecting reliable data for informative decision making. To conduct surveys, we must go to the remotest parts of this nation; not only during election times. Collect reliable data and provide ideal basic services for the health and well being of our nation.

Thank you.

Hi Manuel,

I’m sorry if the title was offensive. It was intended to capture the main findings. The sample size was very large and there is no reason to believe it was unrepresentative, or that there was massive misunderstandings of the questions. There are also three quantitative surveys that show widespread calorific deficiencies in PNG. I hope to write more about them and it will be interesting to see the response.

Regards,

Stephen

The govt of the day must look into such issues and start solving them to contribute to the HDI for this nation, since GDP per Capita is not reflected in such aspects of a nation’s wealth, health and well-being.

Thank you once again to the authors for the invaluable information.

Take back PNG: Prime Minister Marape and his audacious version for PNG.

Manoj and Stephen’s article has raised a very important issue and has attracted many passionate responses. Three days after publication it was referenced on Fly River Forum, a Western Province Facebook Group (https://www.facebook.com/groups/flyriverforum/permalink/3552234178211444/).

The poster reported that ‘Western Province has the most hunger among rural households with half the households hungry’ and provided an illustrative graph. Within a day, there have been 57 responses, both supportive and critical, with many engaging deeply with the issue of hunger.

While I am personally critical of the methodology used in the survey, I appreciate this response by one of the Fly River Forum commentators: ‘It’s amusing to see people defending/denying the fact that the data, to some degree, truthfully represent the situation as it is on the ground. Sampled data may not cover all areas but is enough to give us some indication of what our situation is like. Compare these results with the level of government services as well as infrastructure development, and realize that the trend of being the least developed province correlates with such food security trends. Come on guys, instead of living in denial, we should see this data representation in a more positive way. These results should be an eye-opener for us to at least realize that something is wrong somewhere.’

Hi Stephen, Manoj, thanks for highlighting an important issue. I agree that there is probably a false sense of complacency when it comes to assessments of food security and nutrition in PNG. However, the data that you presented doesn’t shed much light on this. From my own limited experience visiting different parts of PNG I have seen the reality of real ‘subsistence affluence’ in some very remote areas and the contrast with the situation of people in urban / peri-urban settlements who are much more reliant on local markets and imported foods. Of course, these are just anecdotes – we need the data!

At a time when there is real discussion about the health benefits of periodic and intermittent fasting, missing a meal here or there is not something to worry about – it might actually be good for you. However, we should be worried about situations of chronic, or acute food insecurity and the pernicious effects that this can have on health and wellbeing. It should be possible to provide a much richer and more informative assessment of food consumption patterns and nutrition outcomes using data from the DHS and other sources. Is there a reason why you did not discuss anthropometric indicators, dietary diversity, breastfeeding practices, consumption of iron-rich foods, etc., etc.? Were these modules included in the DHS?

Hi David,

The questions have been used in many countries, so I wouldn’t dismiss them so easily. Even if you do dismiss them, I wouldn’t dismiss going without food for 24 hours. That one-third of the population says they have done that in the last year is very worrying, especially when we know, as pointed out in the blog, that three surveys have shown widespread deficiencies in calorific intake.

Yes, there are additional modules on malnutrition. See chs 10 and 11 of this report: https://www.dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR364/FR364.pdf. However, we wanted to challenge the prevailing assumption that there is no hunger in PNG, especially in rural PNG. Hence our focus on the worrying number who have gone for a whole day without eating.

Hi Stephen,

Thanks for responding. I took a look at the DHS report but it does not seem to include anthropometric data on the incidence of stunting, underweight, and wasting in children aged under-5. This is a real shame.

The food security index that is presented in the report is interesting – these composite indices are less intuitive than single measures but they are supported by a carefully developed methodology and should help to smooth out measurement errors. A couple of points caught my eye when looking at table 2.17 of the DHS report. The first is that the confidence intervals for overall incidence of food insecurity in rural and urban areas overlap, so at a national level, urbanization does not appear to be improving food security outcomes. The second is that while the incidence of food insecurity does decline as you move across the wealth quintiles, the rate of decline is quite moderate – for example, 41.6% of households in the top wealth quintile have moderate food insecurity.

Improving food security and nutrition are very important so thanks for drawing attention to the issue. It would be great to see more effort to collect and analyze nutrition data and to translate these insights into programs to improve nutrition outcomes.

Thanks, David

As far as external validity is concerned, you should also present the population sample so that readers will know that your research fairly represent population of Papua New Guinea. Otherwise, your research data is biased and unreliable.

The survey interviewed 16,000 households. It was carried out by PNG’s National Statistical Office. You can find out a lot more about the survey and its results in this report: https://www.dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR364/FR364.pdf

Yes, it true.

But don’t you in the West call it paleo diet with intermittent fasting? Double standards. To you that is healthy, for us it is going hungry.

Maybe they didn’t see anyone who was so fat and obese like they have back in their country, when they conducted the survey in Western Province. So they assume the whole of PNG is a hungry country…!!

These sorts of smear studies & reporting has no place in PNG. So-called academic experts using their academic models and developmental yard sticks to brand this country a “hungry country” is absurd. No one goes hungry in PNG. If they found anyone, they could have rallied all the lazy people who don’t want to work their naturally furtile lands where anything can grow. Load of rubbish. Compare that to india, Pakistan or even Australia…where citizens don’t have direct and free access to aurable land to farm. That’s where you will find a population going hungry and at a brink.

C’mon stop this nonsense please!

Hahahaha

The survey was conducted by PNG’s National Statistical Office.

This is an excerpt from a study I did at Rangwe village, Nuku district, West Sepik Province in 2007:

From 1 July to 1 October 2007, forty-two households were visited three days a week, usually in the evening, on Monday, Wednesday and Friday and asked what foods they had consumed on the days since the last visit.

The time of the day also influenced what was eaten. Of the 2658 meals which included sago, 47% were evening meals and only 18% mid-day meals. Bananas and pawpaw were eaten more often at mid-day meals than other meals and sago and greens were eaten less often at mid-day meals than in other meals.

It was initially thought that the 742 mealtimes at which a household reported they had consumed no food, might indicate which households were short of food. But 77% or 577 out of a total the 742 meal times at which it was reported that no food was consumed, were at mid-day, when people are usually working away from their village homes. In these circumstances they often either do not eat, or more commonly, they snack on sugarcane or a pawpaw and do not count this as a meal. In over three-and-a-half months, at only nine evening meal times did a household report they had not eaten anything and had ‘gone to bed hungry’. While this suggests there is not a shortage of food at Rangwe, I examine which households reported missing a meal below.

The nine households which reported missing evening meals were Households 1 (three times), 10, 20, 25, 29, 51, and 55. They were all above the median for the number of mature sago palms available in 2016 and 1 and 55 were in the first quartile. So, unless their circumstances had changed significantly between 2007 and 2016, the reasons why they missed an evening meal would appear to not include a shortage of available sago palms. Households 1 and 55 are in Quartile 1 (sago-rich), 10, 25, 29 and 51 are Quartile 2 (sago-adequate) and 20 is Quartile 3 (sago-inadequate). The head of Household 1 experiences occasional bouts of a psychological condition, causing him to act in an unusual way. This may have temporarily affected family wellbeing, causing dinner meals to be skipped. The head of household 25 was still mourning the death of his wife and this may have contributed to him and his children skipping meals.

Other circumstances may have contributed to households 10, 20, 29, 51 and 55 who reported not eating dinner meals. It is likely that some households may have had a heavy meal at sago processing facility or garden camp site before returning home, to go to bed without eating an additional evening meal.

Nice work, should inform the author of their misunderstanding of our PNG culture. We are not the western way culture.

If they can’t understand what you just wrote, I don’t know what will.

What significance has the criterion of skipping meals at least once a year? This just asks for unusual events (a long bush trek, hunting or fishing expedition for instance) to sway the results. Also, you do not seem to be worried about “miraculous” convergence of responses between rural and urban environments that are markedly different in all respects, and yet they yield the same answers. This could point to your questions probing human psychology rather than actual environmental conditions. For instance, how different would be the answers from arguably well fed Queensland?

In my country eating meal 3x per day is not our custom, we eat whenever we feel like. Those who says they don’t eat could be those living in towns or urban drift but mostly in Papua New Guinea we own lands to grow our own food enough for the consumption … it shouldn’t be a PNG hungry country. I am employed in formal sector, I don’t spend most of my income on importing good only a bit and most food comes from my backyard garden or market.

Good comments.. speaking the facts.

The survey doesn’t assume that people eat or should eat three meals a day.

This report is totally full of crap!!!…

Whoever did the survey doesn’t understand the PNG lifestyle.

For your information, we in the rural Highlands can eat in bowl dishes… plates are very tiny compared to the size and amount of food that will be served.

The PNG National Statistical Office conducted the survey.

The report for me truly is unsound.

I suppose there is another interest that we can not easily figure out. Using Western Template to measure hunger in PNG does not resonate.

I have land which I own, I have forest which I own, I have waters which I own. Only the lazy go hungry.

Have you seen any malnourished and skinny looking Papua New Guinean? No I don’t think you saw one. There are varieties of abundant fresh vegetables right across the country,banana, sweet and English Potatos, taro, yam, greens, fruits and many more. We are not like most African countries, India, Bangladesh, Pakistan where the food supply is low. Besides Papua New Guinean eat only two main meals, breakfast and dinner. However we do eat varieties of fruits, sugar cane and sometimes heavy meals during the day. No one goes without food in this country except they choose to fast.

Population is growing rapidly in PNG. Birth spacing is decreasing. Pressure on land is increasing. These factors, among others, increase the likelihood that nutritional needs may not be met for many people. There is certainly a need to monitor the well-being of people with respect to nutrition. But surveys of this kind must be done well or their results will be unreliable. As Bryant stressed, the survey questions listed in PNG Demographic and Health Survey could not, as posed, answer questions about hunger in PNG. I think I myself could answer ‘yes’ or ‘probably yes’ to all of them! To accept one person’s response that they had gone without food for one whole day in a full year as evidence that that person’s household experienced hunger is seriously wrong. For 30 years I have been visiting people in the Nomad area of Western Province. A major component of past initiation practices was the requirement that novitiates went without certain things – tobacco, water, certain foods – for hours, a few days or (with some foods) until the time they married. They were being taught that, in the boom-bust environment where they lived, short-falls were to be expected and they had better learn how to live in this kind of a world. In the year of their initiation all these strong and healthy youths and young men could have answered ‘yes’ to all the survey questions. Russ Stephenson has been working on issues of malnutrition in this region, though Covid-19 has postponed follow-up surveys. He is rightly concerned by observations of a high level of malnutrition in children though the possibility of lingering effects from a serious drought and earthquake need to be untangled. There will be people in PNG for whom adequate nutrition is problematic. It is important to learn where, and for whom, problems exist. Regrettably, I do not think the survey summarized in this article addresses either of these needs in ways that would be wise to act upon.

Hi Peter,

50% of respondents in Western Province said that they had gone a whole day without eating, the highest in the country. That seems really good evidence of particularly widespread hunger in that province.

Russ Stephenson in his comment concurs on the basis of his personal observations that hunger is not uncommon (that is, is common) in this region.

Thank you everyone for the comments. In response to a few of the specific queries:

1. The questionnaire wasn’t translated, but the interviews were trained and they translated as needed as they asked the questions.

2. Our understanding is that “whole day” was intended to be 24 hours.

3. If the respondent said yes to not eating for a whole day, it was at least once in the last year. (The survey though was carried out in different parts of the country over three years.)

4. The survey doesn’t assume that people have or are meant to have three meals a day.

5. That’s a very interesting point about eating (or not eating) “real food”.

6. It is certainly true that individual survey questions might get interpreted in different ways, and in unintended ways. However, the eight questions give fairly consistent answers. And three other surveys show widespread calorific deficiencies.

Just some more background on the survey: We should have mentioned that it was implemented in PNG by PNG’s National Statistical Office. The DHS itself is an international survey. These questions on food security were developed by the FAO and have been used in a large number of countries, both developed and developing.

Although we didn’t report it, typically an index of food security is created based on all the questions. The PNG DHS report does this and calculates that 57% of the population of PNG experiences moderate to severe food insecurity. This is actually the average for Sub-Saharan Africa (see Table 3 of this report). The PNG report (which you can access here) also finds that the poor in PNG are more likely to experience food insecurity than the rich.

Stephen and Manoj

Report is crap … please understand our lifesty and the the variety of crops and what we see as a norm in our daily lives before coming up with your so called report. Also taking into consideration the level of literacy because if you just ask someone if they had eaten during the day, they say no even if they had eaten a cucumber or a mango.

There was a comment about enough food but not enough nutrition.

I would suggest this is also seen in urban areas where diets have poor choices with sugary or processed products like white rice.

Rice is a significant staple here but it’s polished (white) with all the balancing nutrients removed.

Your body is only temporarily happy then it asks for more food to find the nutrients it needs.

But more processed food continues the deficit.

Which is why you see people growing larger and unhealthier.

Village food may be simple but it does have better nutrient mix.

We are not a Hungry Nation. We have our resources available that we can make use of but because of our laziness to farm the land we ended up getting hungry.

Don’t compare your lifestyle with ours because we are all different.

Traditionally we are still adapting to our ancestors way of living where sometimes we may skip meals otherwise we have a wide range of edible fruits that we take everyday and this becomes our everyday food.

Agree with what you said. In the rural areas no work, no food or might put it this way, out of thy sweat he shall eat, lazy people should not eat.

I think nutrition is something to be more concerned about than hunger.

In my experience growing up in a very rural village, we don’t always have enough food in the house but we never went hungry. Not once. If I don’t have enough food in the morning, then I’ll go to the garden or into the forest and when I come back home, it’s always with enough food. Not always enough for a “balanced diet”, but food nevertheless.

Neighbors were (and still are) very helpful. If I need some food right now, I can borrow from them. And when they need food later, they know they can always ask me.

As a Papua New Guinean from a rural village, I really don’t agree with the title.

And as mentioned in one of the comments previously, fruits, nuts, vegetables, are not considered real food here.

PNG rural farmers rarely eat three meals a day. Breakfast is often skipped because work needs to be done before the day gets hot or the distance to the farming area is quite far. The only meal eaten as family is dinner, and in most cases is a heavy meal.

Did the study consider this aspect when analyzing its data, or did it use the western lifestyle of three meals per day?

Three meals/day is not PNG’s lifestyle.

This bar graph does not mean anything if it doesn’t have basic stats (e.g. mean, CI..). I don’t see the number of people interviewed, at each province, urban vs. rural, proportions (sample size/population of province)? Categories ‘Rural’ and ‘Urban’ are too broad, you need to be specific. I have a feeling that if you had increased your sample size(s) then you would find that ‘PNG is not the hungry country’ (except probably in urban squatter settlements in Port Moresby and Lae).

I grew up in a coastal village of PNG. Our main meal was in the evenings when we would have balanced meals. Breakfast was light and lunch was made up of fruits and vegetable or nut snacks. Since we lived near the sea, fish was in abundance. We would grill some for lunch and stored most of it for dinner when the whole family sat down to eat together. We had grilled bananas over the fire or simply had boiled kaukau and tea or water for breakfast.

Today times have changed and I am now in my late 50s. I live in an urban area and am privileged to have been educated and I understand the value of nutrition in food. So I raised my children on good and balanced nutrition. On the other hand, I noticed that back in the villages, rice has become a staple diet, overtaking the once famous sweet potato and bananas. When asked if there is food to cook, many younger people say there is no food, meaning there is no rice in the house; even if there is abundance of local or garden vegetables.

So when you discuss that PNG is a hungry country, you might like to consider the type of food in abundance in specific locations studied,and the choice of food people have and at what meal of the day a certain food type is mostly eaten. For example, sweet potato and banana are usually eaten for breakfast but they have been replaced by bread and biscuits in certain rural households. In the very remote villages, where store goods are still rare, many families have very light meals for both breakfast and dinner, mostly starch and green leafy vegetables. Protein is often not readily available at dinner times. Lunch is not usually eaten as a full meal as most people snack on fruits or easily found vegetables around the houses.

Also for most remote rural villages, plentiful

eating is evident only during feasts for ceremonial obligations, for example, during wedding or funerals, when many people gather together to prepare and cook local vegetables and protein like pork and fish, in big amounts.

But yes, good nutrition and its importance in the development of a child or health of the working adult is very important and needs to be emphasized in the villages. Even people in urban areas need to be aware of this as well.

Nevertheless, Most Papua New Guineans in the rural areas really don’t mind the nutrition part of food; as long as they have eaten a meal and are satisfied, they are not hungry.

So, did you witness a very malnourished population in general or even those within your study areas? Have you considered the varying metabolism of people exposed to different nutritional habits or conditions? Even the Western world is considering dietary fasting and other not so common diet practices as beneficial to health and well-being. Some of these populations have done it for generations. In many households, like in the rural areas when you are busy, you don’t feel hungry, so you continue working in your gardens or do your fishing and hunting. So you might eat one or two meals a day. You might miss breakfast because having it might take up your time or make you feel heavy and you won’t be able to work as efficiently as you would want. Hence, the title of your blog can be misleading. Or define your terms to suit the PNG context as suggested by other comments made already.

Culturally Papua New Guineans are not or do not have 3 meals a day in rural areas.

So you normally will not see them trying to make breakfast. They only have it when opportunity presents itself.

Otherwise they just have the main course in the evening.

Yes of course they have others fruits, anything that is edible during the day.

Life is different in urban Areas.

In my village in Jiwaka it is unusual for people to eat three meals a day. Also fruit peanuts, ripe banana, pineapple etc are not considered ‘real food’. So if someone has eaten fruits etc, they might say, “mi no kaikai wanpela strongpela kaikai” i.e. I haven’t eaten real food. Are those kinds of differences considered as well in this study?

Although my experience is limited (UPNG 1975-79, Rotary Foundation Project to Alleviate Malnutrition in WP 2017-), I concur with the authors that hunger is not uncommon. I commenced my project in the Strickland Bosavi region (Upper/Middle Fly) of Western Province in November 2018 and food was short throughout the region then. I personally witnessed hunger. One young man doing my train the trainer course had to take a day or two off so he could go looking for bush tucker. My course ran for 2 weeks and, during planning with my in-country collaborator, Sally Lloyd of Mougulu, I wanted to make provision for catering in my meagre budget but Sally told me that she would ask participants to bring food with them. Of course, they had no food to bring and our meagre rations left many participants hungry. Despite these hardships, the volunteer trainees completed the course in good spirits. Of course this mini taim hangre might have been the exception, but I do not think so.

Although hunger exists (which it should never be in 2021), perhaps the even more important issue is the malnutrition that occurs, even with a full belly. The limited local diet is invariably low in energy, certainly low in protein and in fats and oils. My emphasis is on the nutrition of pregnant women, breast feeding mothers and children from conception to 5 years old. The productive capacity of the next generation is seriously limited by a poor diet and an unacceptably high incidence of malnutrition at critical stages in the child’s development that may impact on their productive capacity later in life. The importance of this can not be overestimated!

Regardless, all people in PNG (men, women and children) deserve the luxury of a plentiful diet of nutritious food that enhances their wellbeing and quality of life!

Going to the garden is a daily chore in the village, just like you going to work daily. Obviously people need to stock up supplies , so holding them in a workshop for 2 days or more means their rations are low, so they need to be excused. Life in rural areas is gender specific. So when a person takes leave does not mean they are hungry. There is a family depending on that person to bring in the food. So you have to be sensitive to village systems before locking them up in trainings.

Dear Tanya,

Thank you for your comment. I fully understood the need for my friend to go and collect food for his family. No one was locked in. Everyone there came as volunteers. The young man came back, and was welcomed back, when he had provided for his family. The point I sought to make was that food was scarce and that many people were hungry at that time. Hunger does not imply that they had no food, but it certainly meant that there was insufficient food to fully satisfy their hunger.

Cheers,

Russ

As a novice, failed to understand what does “Went without eating a whole day” means. Does it means “At least Once Per Year” or does it means “At least Once for the duration of the study” (2016 to 2018)?

Shouldn’t it also be compared with the statistics of developed and developing countries.

What’s the main reason behind the same, is it the choice of crops, size of farm, soil composition, weather or food spoilage due to lack of storage/ transportation/ distribution infrastructure

Furthermore, why are we discussing just about hunger and not nutrition.

Nice work Manoj keep it up

What is “a whole day”? How was that translated into Tok Pisin? Were all those people in Western not eating during the day while they made sago for a meal that night? Many other questions are difficult to understand e.g “kinds of food”; “skip” (many PNGeans do not assume a 3 meals a day diet is normal – only us overweight in developed countries folk do that); “ran out” – possible, so get up early and go to the garden, or ask a neighbour for a sweet potato and give her one back the next time she needs one.

Sample surveys like this are not the way to investigate “hunger” and many of the questions suggest a non-PNG way of defining what “hunger” is.

Just a thought experiment: would you say the same thing—that nationally-representative surveys are not the way, and that we need PNG-specific definitions—about the domestic violence statistics gathered from the same survey?

I don’t know. I haven’t seen the questions people were asked about domestic violence. But in any survey, let alone cross cultural surveys like these, the terms used must be tested to see if they have the same meaning in English as they do in Tok Pisin and even if when do, can the answers be used to define a condition.

In the case of the word “hungry” (I have only seen the questions listed in the Blog) it seems that the survey placed importance on things like three meals per day, never missing a meal, not having enough to eat and so on. The responses to these questions defined whether a person suffered from “hunger”. Ever since I lived in a village for 18 months and accompanied people to their gardens or other places, I have stopped worrying if I skipped a meal, or even if I feel hungry – it goes away after a while. It’s a common thing in rural PNG not to eat regularly nor to satisfy hunger immediately.

To answer your question I need to know how was “domestic violence” defined in the survey. It is usually thought as physical violence but in Australia “coercive control” is now recognised and it may have no physical violence associated with it at all. In addition, violent acts or acts of coercive control are probably easier to remember than how much or what you had to eat. So questions about them may be more legitimate.

I should also say that I have almost no experience in PNG urban settings.