Budget deficits have become a noticeable feature of the PNG economy over the last decade or so. Less appreciated, however, is how actual revenue collected and expenditure spent (as presented in PNG’s final budget outcome documents) compare to the expectations that are outlined in the budget.

Some degree of error is of course part and parcel of forecasting things into the future. This affects revenue in particular as a function of economic activity, while expenditure usually follows on from government policy decisions. Nevertheless, the more inaccurate future revenue projections are, the harder it is to make forward-looking policy choices and plan future spending sustainably – and the more likely it is that expenditure overruns and budget deficits will persist in PNG.

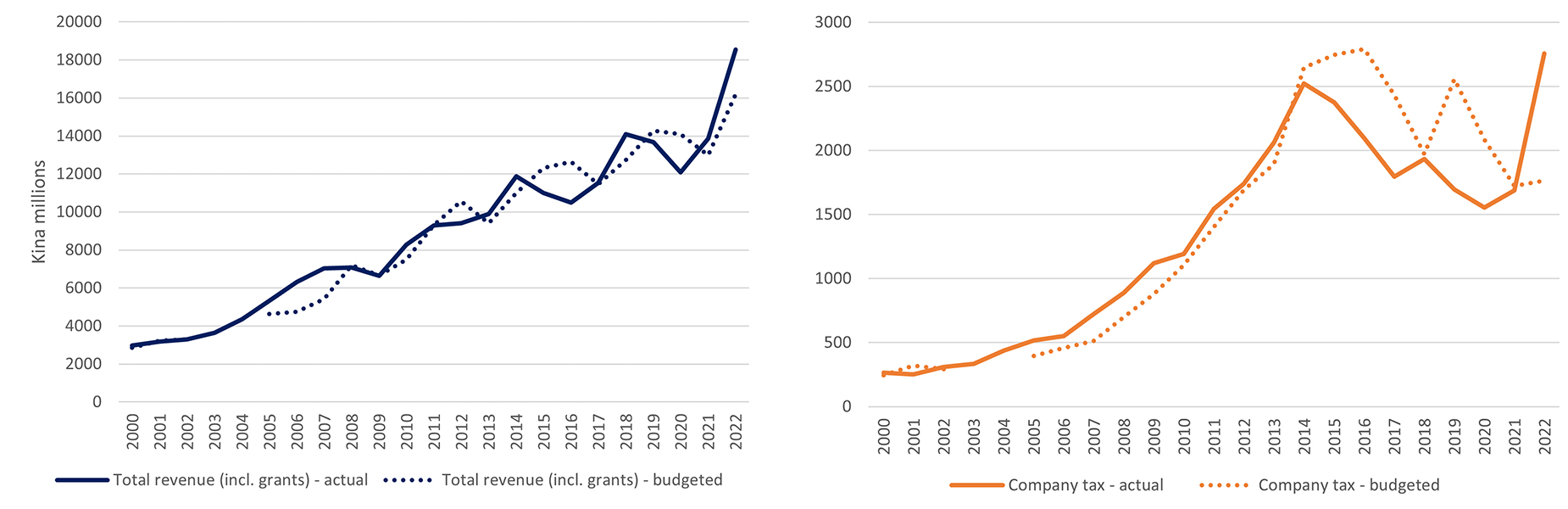

Until the end of the boom in 2014, revenue receipts were usually close to or exceeded projections (Figure 1, left). From then on, significant declines in government revenue due to the economic bust and later the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 were clearly unanticipated. While the decline in government revenue seen in 2015 and 2016 was driven by lower-than-expected collections of all major taxes (personal income tax, company tax and GST), the initial drop in revenue in 2019 prior to the COVID-19 pandemic highlights continued optimism in company tax projections compared to collections, at least until 2022 (Figure 1, right).

Figure 1: Total revenue (left) and company tax (right), actual vs budgeted

Note: Company tax collections as reported in the budget and Final Budget Outcome do not include company taxes paid by resource companies; these are captured under mining and petroleum taxes.

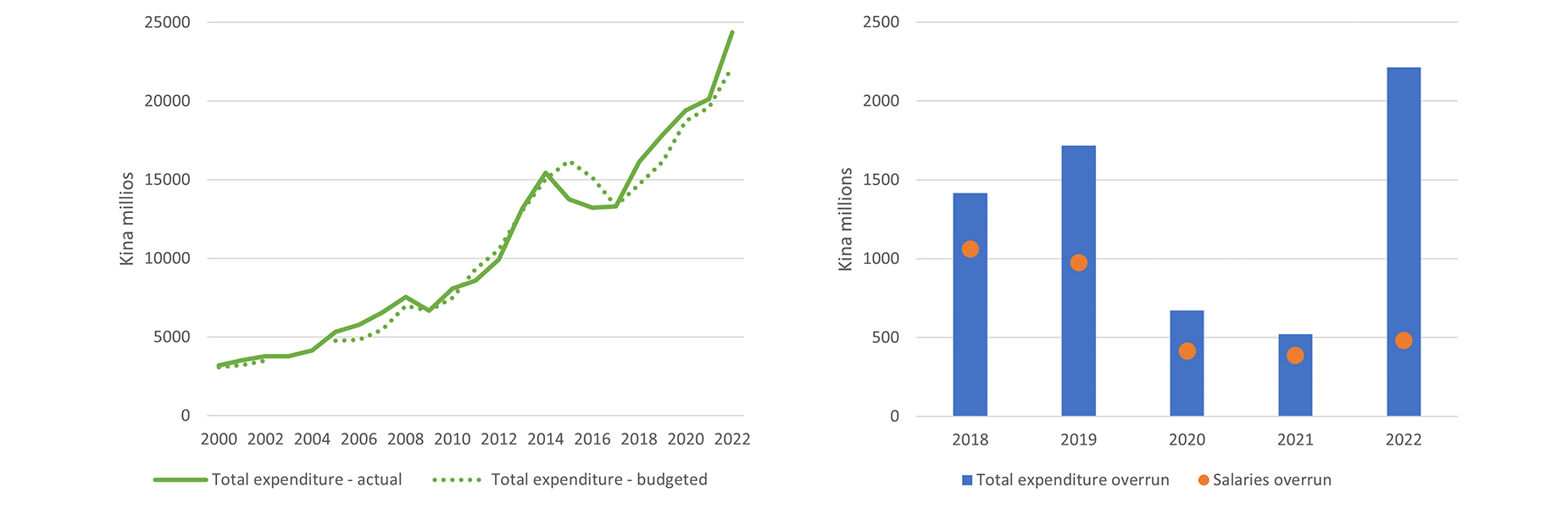

Looking at the other side of the balance sheet shows that expenditure has consistently exceeded budget appropriations in PNG. Since the year 2000, expenditure has gone over expectations outlined in budget documents in 16 of the 21 years for which data is available (Figure 2, left). Expenditure has only been lower than expected between 2011-12 and immediately after the boom ended between 2015 and 2017.

The worst period for overspending was the boom period between 2005 and 2008. In that period, expenditure was on average 14.7% higher each year than budgeted. More recently, from 2018 until 2022, actual expenditure has exceeded budgeted appropriations each year by an average of 7.3%. Somewhat surprisingly, overspend was relatively modest during the COVID-affected years of 2020 and 2021 (3.6% and 2.7% respectively), in comparison to overruns of more than 10% in all other years since 2018.

Figure 2: Total expenditure, actual vs budgeted (left); and salary and total expenditure overruns (right)

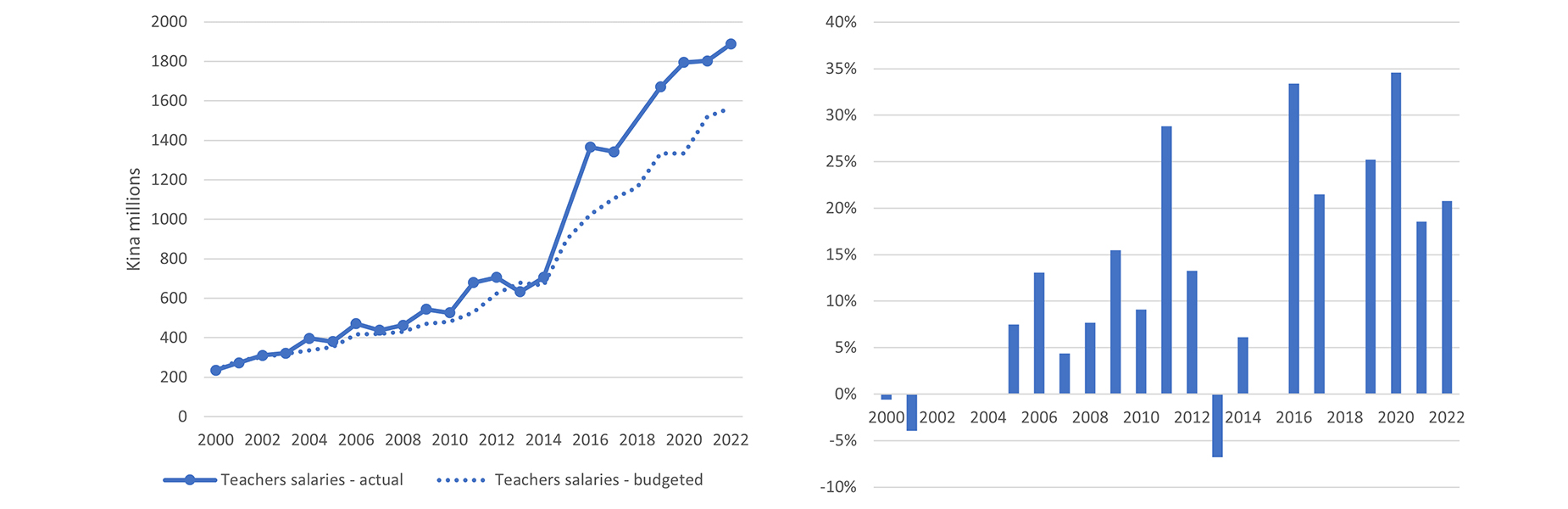

The recent largesse has been driven in large part by overspending relative to expectations on salaries (Figure 2, right). Much of this is the result of larger than expected salary bill for teachers (Figure 3, left), who comprise around half of the public sector workforce in PNG. The mismatch between expected and actual teacher salaries seems to be a problem that has grown over time (Figure 3, right). Between 2000 and 2010, actual teacher salaries were on average 6.1% higher than expected in budget documents each year. But from 2011 onwards, overspend reached an average of 17.3% annually. While 2021 and 2022 have shown some improvement, recent levels of overshoot remain higher than most of the early 2000s.

Figure 3: Budgeted and actual teachers’ salaries (left, current kina millions) and % difference between budgeted and actual teachers salaries (right)

Note: Data on budgeted teacher salaries is unavailable from 2002 to 2004, and data for actual teacher salaries is unavailable for 2015 and 2018.

What is driving growth in both budgeted and actual spending on teachers’ salaries, as well as the consistent and large overspend observable since the mid-2010s? It’s unclear whether many more teachers are being employed, which would naturally increase total salary costs. The Treasurer stated in his 2023 budget speech that there were 59,307 teachers in PNG in 2022; this is not much higher than the 57,600 teachers who were on the Alesco payroll in 2015 (2019 Final Budget Outcome, page 20) despite the explicit focus on hiring more teachers to bring student-teacher ratios down as part of the PNG government’s previous tuition fee free policy. Teachers’ pay rates have on the other hand increased substantially. Base grade teachers’ fortnightly incomes rose from K390 to K900 between 2010 and 2016 alone (2017 Budget volume 1, page 59).

Another factor in rising teacher salary costs is that while teachers are employed by provincial-level governments, their salaries are funded by PNG’s central government. Provinces regularly overspend on teacher salaries relative to their allocations from the central government, to which the central government has responded with increasing allocations in following years. This moral hazard problem makes it difficult for the central government to directly control spending on teacher salaries.

What should be done going forward to ensure expenditure adheres more closely to budgeted amounts? Given the need to consistently fund education, one option would be for the central government to disburse set amounts to provinces on a regular basis, with any shortfalls between appropriations and actual teachers’ salary bills to be filled by provincial governments. Existing work to control the salary bill should also continue through the Staffing and Establishment Review for teachers in 2023 and the Organisational Staffing Personnel Emoluments Audit Committee (OSPEAC), including the retiring of public servants upon reaching the retirement age and enactment of hard ceilings and better recruitment policies.

On the revenue side, the difficulty of anticipating international shocks, and their clear impact on PNG’s government coffers, makes it especially important for the government to implement the sovereign wealth fund and use resource revenues to smooth such fluctuations. More needs to be done to understand what has driven substantial real declines in company tax collections (excluding the increase in 2022) to make future projections more informed and accurate where possible.

As I and others have argued elsewhere, reducing PNG’s budget deficit will be a difficult task going forward. Ensuring expenditure remains within budgeted limits as much as is possible, and improving revenue projections to guide future expenditure decisions, would be a useful step to help with this process.

This blog uses data from the PNG Budget Database (which has been updated to reflect the 2022 Final Budget Outcome figures), and additional data collected by the author from previous budget and final budget outcome documents.