In the accompanying post to this one, I showed how the volume of health, and particularly malaria data, collected in Papua New Guinea (PNG) through the country’s National Health Information System (NHIS) has been steadily increasing over the past decade or so, but that it was not being effectively used. In this post, I conclude the story with an examination of four questions: Why isn’t the data used? What are the costs of excessive data collection? Why has the data system been designed to collect too much data? And, what can be done about it?

Why isn’t the data used?

There are many reasons why NHIS (and other health-related) data are little used. First, there may be a lack of capacity to prepare, analyse and interpret the data, particularly at the provincial level and below. Second, there is limited guidance on how to act on certain observations and, in most instances, there would not even be any direct operational relevance in the detailed disaggregation provided. Third, financial resources at subnational level may be too constrained to readily act on new findings and in the specific case of malaria, the control efforts may be seen as a vertical national program.

What is more, key stakeholders may even have difficulty accessing routine NHIS data either for technical reasons (e.g. internet connectivity at the subnational level, or because the set-up of the user interface does not easily allow the extraction of primary data for analysis), or due to difficulty in obtaining permission to access the data. Yet, if data is meant to inform decision-making (and ideally improve accountability), it should be easily accessible for anyone who has a valid reason.

What are the costs of excessive data collection?

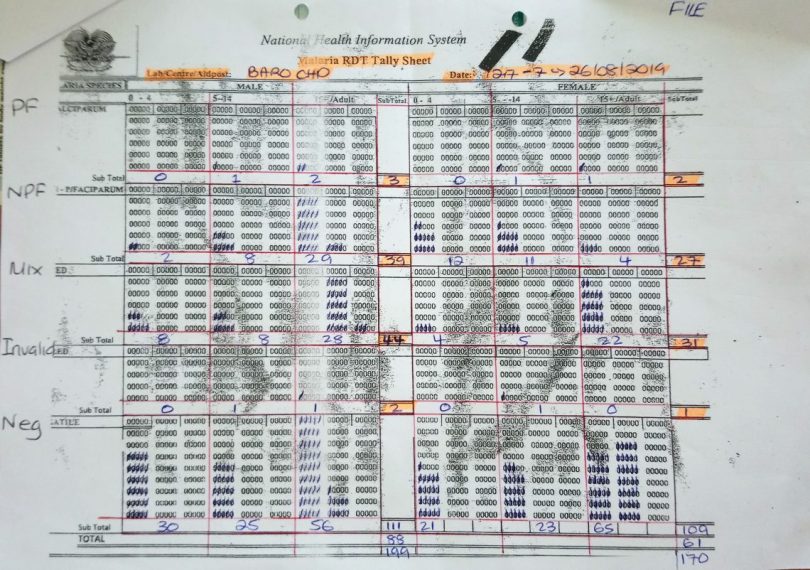

Further, there are valid concerns over the impact of the increased reporting burden on data quality. A review of ‘Monthly Report’ data shows, for example, that in the electronic NHIS database malaria indicators on page 1 often do not add up with the indicators on page 2 from which they were supposedly derived. As all indicators are digitised anyway, it is questionable why health workers have to add them up manually. Anecdotal evidence and personal experience suggest that health workers have in the past had quite different interpretations of how forms should be filled. Besides, the brunt of the work of collecting and reporting the data is borne by a health workforce that is understaffed, ageing, busy with managing patients in very challenging environments, and who – alongside the communities they serve – rarely benefit from all the data they collect. How likely is it that sufficient attention is then paid to reporting requirements when the forms become more and more complicated to fill? Of course, the concerns about quality reduce the likelihood of the data being used, creating a vicious cycle.

Merely satisfying a thirst for data – without prospect for tangible local benefit – does not justify burdening hundreds of health workers with additional data collection tasks. It is important to realise that changing reporting forms, and increasing the amount of information collected in the forms is far from costless. It requires resources to train and continuously supervise those expected to fill the forms, and it poses a growing burden on health workers, who are a very limited and precious resource (in PNG and elsewhere). The opportunity cost of collecting data that remains largely unused may include reduced time spent on clinical duties, outreach activities, or other essential administrative tasks such as drug stock management.

Why has the data system been designed to collect too much data?

So, if the ever-increasing amount of data collection by the PNG health information system may be doing more harm than good, why then is so much data collected?

The basic answer is that development partners and international organisations are fond of data. Data is generally seen as paramount to accountability. But the focus is too often on quantity, not quality.

Initiatives by the World Health Organization (WHO) have contributed to health data across the world becoming more standardised and hence more comparable. But WHO guidance on core indicators and their required disaggregation suggests a level of detail in routine data that is difficult to reconcile with the capacity of health information systems in many low- and middle-income countries.

The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, the major funder of malaria control in PNG and globally, uses specific malaria indicators to track progress, such as the “proportion of confirmed malaria cases that received first-line antimalarial treatment according to national policy at public sector health facilities”. This indicator, if assessed through the NHIS, requires recording treatment administration stratified by diagnostic method (i.e. diagnosed based on clinical signs and symptoms, or using a laboratory confirmation such as a rapid diagnostic test or microscopy). Since, in addition, cases are recorded separately by age group, sex and whether they are an outpatient or inpatient, recording the monthly number of administered treatments requires filling 28 fields in the ‘Monthly Report’ form. This is required every month at 800 health facilities. For one reporting indicator.

What can be done about it?

The way forward is tricky. It is comparably easy to add indicators and data collection mechanisms to a health information system, but more difficult to remove an indicator. To date, initiatives to strengthen the health information system in PNG have not managed to disentangle the complicated web of partly overlapping, partly complementary, data collection systems. Instead, some weaknesses are patched-up by adding new and independent data collection mechanisms, such as a mobile-phone-based system for reporting of disease outbreaks directly to the national level. While new and innovative tools may have clear advantages (such as increased timeliness and accuracy), they should be embedded in an overall coherent strategy and ideally be integrated into a single electronic platform that stakeholders at national and subnational levels can access.

The focus should be on collecting “minimal essential data”. Routine reporting systems should collect a limited set of key indicators and for each of them, there should be a solid justification. The indicator definition should be guided by the World Health Organization, and the selection must consider legal obligations under the International Health Regulations. But a country should consider carefully which information it requires for decision-making and which data has to be reported from every single health facility for every single month. Data that is not required at this frequency or resolution might rather be collected in sentinel surveillance sites (where adequate resourcing and data quality can be ensured), through surveys, or research studies. In the case of malaria data, one might, for example, consider abandoning age group stratification in the NHIS and collect age information in selected surveillance sites, such as the ones maintained by the Papua New Guinea Institute of Medical Research (PNGIMR). This way, the burden is shifted from the clinical health workforce to dedicated specialists tasked with informing the government.

The story of the collection and use of malaria and health data in PNG is far from unique. A disconnect between health data and certain public health decisions can be found in countries at all income levels. But particularly in over-stretched and underfunded health systems, donors need to step back, and governments need to rethink. Of course, data is crucially important – but with the right balance between quantity and quality. Most importantly, a health information system must be owned locally and designed in a way that is consistent with the country’s capacity to operate it and utilise the data for improved programmatic decision-making.

This blog is part of a series. You can find the first blog here.

Malaria data

I agree with the author that filling out the current NHIS malaria data sheets, elevating and collating that information into a useful management tool for use at any level is fraught with issues. Elevating aid post records, sometimes months after the event to the NHIS begs the question as to what use it is at that stage.

What are the issues that impact upon the quality of the data collected? Firstly, not all aid post workers have malaria data folios issued to them on which to record presentations. Secondly, there is a real question mark over accuracy of the diagnosis for those who do.

If the standard issue rapid diagnostic kits are not available, the health worker may have to make a clinical assessment based on the symptoms of the patient. Assessments of clinical diagnosis versus gold the standard of microscopy reveals that workers who have to rely upon clinical diagnosis tend to record a positivity rate up to thirty percent higher than it actually is.

Further clinical diagnosis is unable to delineate between a purely blood stage malaria or one with liver dormancy. The usual outcome is to assume the latter and record a mixed species infection which inflates that metric.

When RDTs are used there is a tendency by workers pressed for time to shortcut the correct development time and misread the test strip.

In reality very few of the 8,000 contributing sites have access to a functional microscope or a WHO accredited level a 1 or 2 microscopist.

Less experienced lab techs have a tendency to miss P. vivax altogether or misread the ring stage as P. falciparum, resulting in data in either case being erroneously skewed towards the latter species. Under these circumstances RDTs have been shown to give more accurate results than inexperienced microscopists.

There is a need to ensure that workers at every level are constantly supplied with RDTs and that community health workers in particular are provided with in service refresher courses to ensure they continue to read RDTs correctly.

Then there is the issue of how best to utilise the data that is recorded. Let’s be clear, depending upon the local geography malaria incidence can vary markedly between communities along a 20 km stretch of coastline.

Those close to creeks with still water lagoons may suffer incidence in the order of 100 (100 positive presentations per 1,000 in the population per annum) while communities located in drier locations might see incidence of less than 20 over the same period.

Then there is the question of speciation. Does a community have the normal distribution of parasitic infections or is it skewed towards vivax or falciparum and which age group in family is presenting with symptoms?

From the perspective of a local level government or district health manager this information is important and should inform the type of response, particularly in relation to community awareness and the vector control measures he or she recommends. The question then is do they get this information and if yes, do they act on it?

In my experience visiting aid post workers in different locations throughout the country the answer is more likely to be once data sheets are collected, they never hear about them again.

As for how the raw data is used at the level of the NHIS, I have yet to meet a district or LLG level worker who has received feedback courtesy of the NHIS.

I agree with the notion of sentinel sites, but unless PNGIMR is properly funded it is doubtful their staff could monitor a sufficiently large sample to adequately to provide the level of national data coverage needed.

If there is to be greater value obtained at the local level, I would suggest the focus be placed upon district level collection, analysis and appropriate action in accordance with the results.

A useful discussion on the collection, relevance and application of health data, which can also apply in principle to the routine or survey collection of other demographic, social & economic ( incl agricultural) data. Largely, PNG is highly deficient on routine and reliable data, although, as with basic population data, there are multiple partial, or partially completed, data collection vehicles rolled out by different institutions. Two principles need to be applied: firstly, restricting and agreeing to the relevant information required, both from routine collection, and specific surveys, and, second ensuring that the information, other than any patient- confidential material, is accessible openly and freely, to enable the national sector authorities, including Health and IMR, have access, but also wider institutions, researchers, and civil society organisations can also access it, both for analysis and accountability purposes.

One shouldn’t bring the bar to low, and assume deficient health sector institutions for ever, but provide what should be competent, if uncoordinated institutions to access priority and timely data, in parallel with seeking to restoring and upgrading that capacity. There are certainly many capable individuals working in the sector who both provide and demand sound information … like the impressive team who’ve been working on TB out of the Kaugere sub- hospital, etc … so making the data, and analysis of it, both widely available, but also in a relevant and accessible format are also crucial, and, as stated, this also applies in other sectors, where routine and extensive data is not being kept, nor has been for many years …

I just found some spare time to read these two blogs. I do agree that the Global Fund might not be the most “easy” donor when it comes to data collection and indicator reporting. However, I am opening a debate on the potential cleanup of data collected-what are the things we can potentially remove from the current data sets? What are the domestic needs in terms of data and then the ones that are donor driven? How to align?

maybe a valid discussion as we might enter into malaria elimination investment soon and we will need to add elimination specific indicators:-)

Thanks to everyone supporting this amazing country!

Too much focus on data collection can sometimes be to the detriment of actual service delivery in fragile health systems. In Nigeria, donors come with their own data tools and incentivize health workers to fill them to the detriment of the National tools. The cost of printing and dispatching mountains of paper tools to the thousands of health facilities is not often discussed. Because of cost, several health facilities have no tools with which to report to the national Health Management Information system.

Apart from the greed for more data, let us also mention the incompetence/inexperience of those who respond to this hunger by designing, heavy, complicated instruments. An instrument is not just a list of questions…it’s meant to be a tool and can only be as good as the operator’s capacity to understand and use it. As you rightly pointed out, our health workers are under-skilled, under-equipped and overworked. The data from the NHMIS reflects this..

Dear Liz,

interesting to read your insights from the other side of the world. Evidently, the issue is one of global proportions.

While it has become easier in recent years to handle large amounts of data and automate data presentation (e.g. on dashboards), it is sometimes forgotten that i) someone needs to collect the data and ii) preparing a nice graph should not be the end of the procedure but the beginning of a process of interpretation and translation into public health action.

These are two interesting and thought-provoking blogs. The case for focusing on “minimal essential data” is well made. While I agree there is a need for streamlining the data collection on health outcomes, I think there is also a case for increasing the collection – and use – of some of the basic costs of health service delivery. It is quite noticeable in a number of countries that there is little, if any, useful data collected on the actual cost of delivering a particular health service. As a result, there is no real basis, or incentive, for exploring more affordable or cost-effective alternatives. The lack of relevant data on costs is particularly noticeable in some “pilot programs” and / or when tracking how unit costs change – for example increase or decrease – as a particular new program scales up. Including some “minimum essential” data on relevant costs could therefore be part of the mix when considering how to make key health data more useful, and used.

Dear Ian, you are making a very good and important point! There are certainly areas in which we lack sufficient data, such as the cost of service delivery you mention, but also the effective coverage of interventions and determinants of health outcomes, to name just a few. The two key questions to ask ourselves would then be: i) what are ways of collecting such data without overburdening the system, particularly service delivery, and without generating unnecessary parallel systems, and ii) how can we ensure the data is useful and used for decision making for the benefit of the people in PNG (or any other country). Part of the answer to question ii) I see in the development of strong local capacity, including leadership capacity, which is a long-term undertaking, rather than a quick fix.