Police in Papua New Guinea (PNG) generally cop a fair share of criticism. This is particularly true in my area of research, sorcery accusation related violence (SARV), where police are often unwilling or unable to intervene – and sometimes even the instigators of violence.

Yet, during my research, I regularly came across cases where – miraculously given the lack of resources – police officers had made a positive impact in the fight against SARV. There were police officers who turned up at a remote torture scene and, through sheer determination and oral dexterity, talked down a whole village from perpetrating more violence. There were police officers who sheltered victims of SARV in their own homes. There were police officers who, for years, worked hand in hand with local human rights defenders intervening to save dozens of lives. There were police officers who set up anti-SARV measures in their own communities to attempt to ward off the evils they saw happening around them.

Intrigued by these examples, I set about trying to work out how they did this, and what we can learn from these cases about policing in Melanesia more generally.

I found that it was very often the relationships and networks of individual police officers that both motivated and enabled them to carry out their policing duties in the face of daunting obstacles.

Four strategies enabled effective policing of SARV:

- police forming coalitions with local powerbrokers and community members, to both engage in preventing and intervening to stop violence, and to rescue those being accused

- police supporting the informal mediation of sorcery cases

- police offering the accused refuge inside the police station and remand cells

- police offering personal support and their own resources to care for victims of SARV.

How the police chose to use these strategies, and what motivated them to do so, varied considerably and was highly localised. But four clusters of motivations were dominant:

- perceptions of their obligations to provide security for those seeking their support (“They came to me for help. I was the only one”)

- religious (Christian) convictions (“That’s the role we have. God has given me the wisdom to talk”)

- desire to maintain peace in their own communities

- compassion for the victims, arising from a shared sense of humanity (“I had no choice. I could see she needed help”).

These responses highlight the role played by the ethics of kindness, integrity and concern for the wellbeing of other humans – factors not often at the forefront of discussions about policing in PNG.

So what do these findings suggest about policing in Melanesia? Critically, they make it apparent that policing occurs within a complex system comprised of a multiplicity of actors and structures – state resources, private security, church networks, aid and development programs, and so on. Police officers, like many other state actors, exist within a relational state as well as a bureaucratic state, as my colleague Gordon Peake and I have suggested elsewhere.

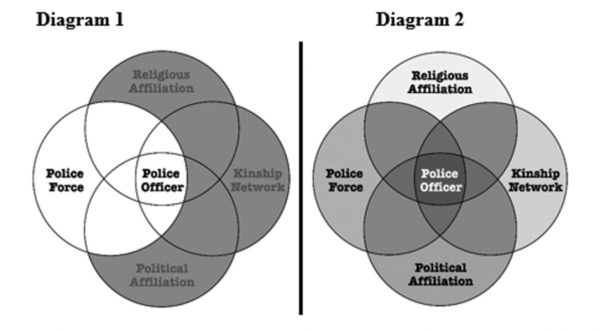

As such, it helps if we can understand the police as adaptive actors within the system, embedded within a range of relationships that all have importance for performing policing. This framing requires a different view of police officers to the more usual conceptualisation of them, shown in Diagram 1, where their identity as police officer is paramount and other relationships are in the background. In Diagram 2 we see a police officer in a relational framing. Here, the police officer’s identity is kaleidoscopic, with a range of different relationships foregrounded, all or some of which may influence the policing role – for better and for worse – in particular contexts.

This insight in turn suggests a range of approaches to policing that challenge the existing emphasis on vertical authority structures and tight discipline – the type of policing often emphasised in foreign assistance training programs.

One possible analytical approach for utilising such a model involves the following steps:

- What relationships are operative, and how do they operate in particular contexts?

- What barriers prevent certain types of relationships leading towards negative policing outcomes?

- What conditions stimulate relationships to be oriented towards positive policing outcomes?

I’ve explored how such a model can be utilised in regard to policing SARV in a recent article. The key insight is that, rather than trying to ignore or minimise emotions and relationships in policing for fear of corruption or nepotism, we do better to view them in a clear-eyed fashion for both their strengths and their weaknesses. Only then can we truly understand the range of accountability, resources, authority and legitimacy that police in a relational state really possess.

Read the article Policing in a relational state: the case of sorcery accusation-related violence in Papua New Guinea.

Thank you for the reflection and insights Professor.

Thank you for this insight, RPNGC is not given enough credit and publicity for their positive work in rural areas to ensure community harmony. In collaboration with village courts representatives, RPNGC are seen by many as the representatives of government in the absence of other formal state institutions. They give confidence to a community where leadership, confidence, trust and consensus is so important.