The direct distribution of natural resource wealth through cash transfers has been recommended to avoid the political and institutional curses that natural resources can bring. By removing resource rents from government, putting them in the hands of the people, and then claiming some of the revenue back through tax, incentives to undermine public institutions will be removed, corruption can be avoided, accountability and transparency will grow, and the benefits of natural resources will be more equitably shared. Or so the argument runs.

But what about the actual experience with so-called ‘resources-to-cash’ transfers (often referred to as ‘oil-to-cash’)? The Center for Global Development (CGD), a leading advocate of the proposal, has put the call out for countries to learn from the successes and mistakes of those who have experimented with it. There is virtually no literature on such transfers in developing countries.

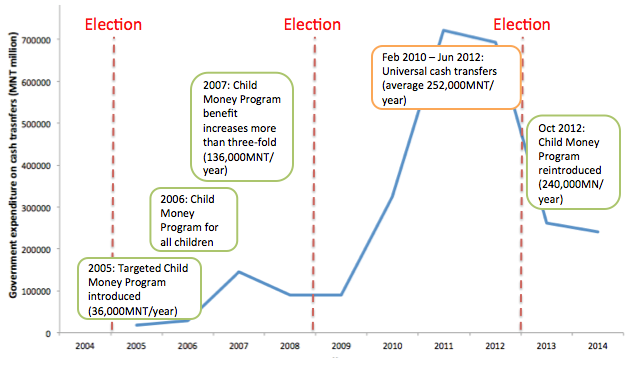

The paper we have just written on Mongolia aims to fill that gap. Resource-rich Mongolia is perhaps the only developing country that has actually introduced a resources-to-cash scheme. As the figure below shows, in 2006, Mongolia introduced resource-financed payments for all children, and in 2010 the scheme was expanded, with larger payments to be provided to all citizens. In 2012, the scheme reverted to being one for children only.

Figure 1: Mongolia’s resources-to-cash history

Although Mongolia retains universal child transfers, it has effectively moved away from the resources-to-cash model by announcing that it will delink their payment from resources revenue. The new resources (or sovereign wealth) fund that it is establishing will not be even partially earmarked for cash transfers.

How did Mongolia’s resources-to-cash experiment fare and why is it being abandoned? The new transfer payments significantly reduced poverty and inequality. But the scheme was poorly designed and implemented. The link in practice, as against in intent, to resource revenues, was weak. Payments were based on election promises, rather than actual resource earnings. This meant that, at some points, cash transfers actually exceeded mineral revenue, and the gap had to be met by borrowing. Thus resources-to-cash increased debt and may have added to inflation.

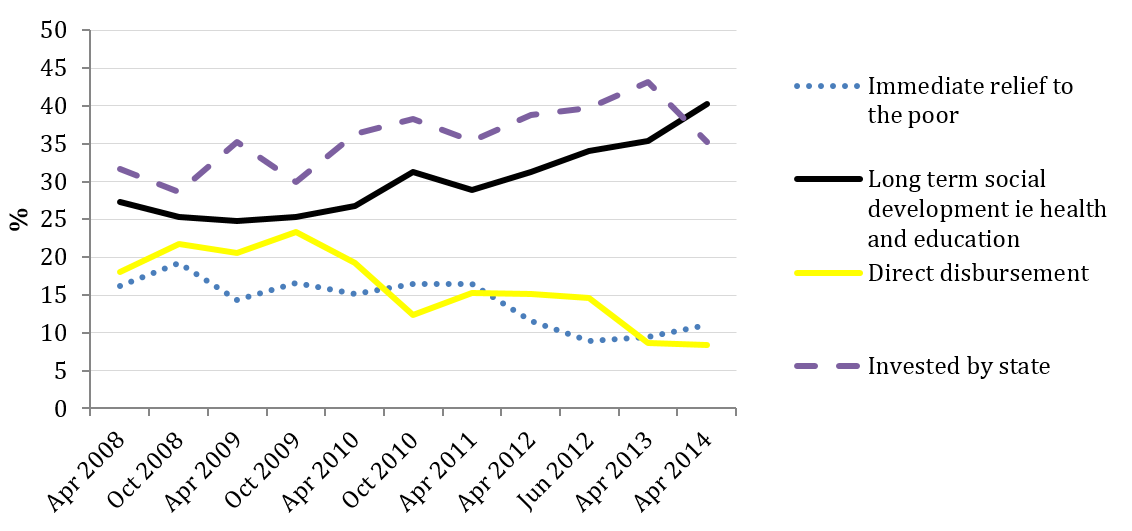

These design and implementation flaws also led to the scheme losing political support. The Sant Maral Foundation conducts a biannual opinion poll of political and social issues in Mongolia. Figure 2 shows the responses from 2008 to 2014 to the question: “Through recent development of the mining sector Mongolia has gained considerable wealth. How should this money be used?” “Direct disbursement” was never a particularly popular answer to this question, but its popularity has declined from a peak of 25 per cent when the idea was first publicised to under 10 per cent most recently. From interviews we learnt that Mongolia’s resources-to-cash experiment came to be seen as wasteful and irresponsible, and even as an abuse of the political process. (The child payments were introduced in the course of the 2004 election campaigns. In 2008, parties competed over the size of the transfers they would authorise. By 2011, the Election Law was amended to remove this practice.)

Figure 2: Public support for different uses of mineral wealth in Mongolia, 2008-2014

Source: Sant Maral Foundation (2008-2014)

What lessons can be drawn from the Mongolia experience?

Todd Moss and his co-authors in their just published book Oil-to-cash: fighting the resource curse through cash transfers don’t say much about Mongolia, but do write that the country’s experience “demonstrates the potential popularity of Oil-to-Cash and its political feasibility under a competitive electoral system.” While this is a fair reading of the 2004 and 2008 elections, one might also say that subsequent experience demonstrates the ultimate political unpopularity and unfeasibility of resources-to-cash. Such a conclusion would be too strong, but Mongolia’s experience certainly points to the risk of support for resources-to-cash being undermined by poor design and implementation.

Our findings provide backing for Alexandra Gillies, who, writing about resources-to-cash in 2010, cautioned: “policy mechanisms tend to reflect the environment from which they emerge. Direct distribution [resources-to-cash] may offer the greatest expenditure efficiency gains in countries where governments fail in providing public goods[;] however, its implementation will be the most difficult in these same contexts.” As a young democracy, Mongolia has fledging, weak institutions and a political environment prone to short-term decision-making. These weaknesses pervaded and undermined, probably fatally, many aspects of its resources-to-cash scheme.

We are sceptical of the idea that resources-to-cash schemes will strengthen accountability by enhancing taxation. We are only aware of two resources-to-cash schemes: Alaska’s and Mongolia’s. In neither are the transfers taxed, nor have their tax regimes changed as a result of introducing the payments. In any case, in developing countries, systems of direct taxation are very weak, and typically applicable only to the formal sector. Even if transfers were taxable, most recipients would not pay that tax.

Various mechanisms have been put forward to solve the resources curse: investment in infrastructure and human capital; sovereign wealth funds; and now, resources-to-cash. If implemented well, these mechanisms should all help avoid the resource curse. But there is no reason to think it is easier to implement resources-to-cash than the other proposed mechanisms. Perhaps it is easier to give away cash than to build infrastructure, but, as Mongolia shows, the very ease of handing money out also makes it easier for this option to blow the budget.

Overall, Mongolia is a cautionary tale. One should certainly not dismiss the potential benefits of resources-to-cash on the basis of one, poorly designed and implemented instance. Rather the lesson of the Mongolia experience is that resources-to-cash needs to take its place alongside, rather than be favoured over, other policy instruments that have been recommended for resource-dependent economies.

Ying Yeung is currently an Overseas Development Institute Fellow at the Ministry of Education and Vocational Training, Zanzibar. She undertook the research for this paper when working with Devpolicy. Stephen Howes is Devpolicy Director. Thanks to the International Mining for Development Centre for their funding support.

Thanks for the analysis. Interesting that it happened this way. It seems some recovery is underway now though and hopefully the government and more importantly the civil service that survives political change have taken on lessons from the past. To keep up to date I usually use the business council’s website as well as http://www.resources.mn for specific mining in Mongolia news due the their quick coverage of legal and regulatory environment.

Very good post. The analysis of the Mongolia experience has high relevance for Papua New Guinea. My understanding is that your analysis clearly shows the limits of the ‘resources to cash policy’ and particularly the need to pay more attention to building national institutions for the longer-term, I agree with this. I would add however that it is vital to get the balance right during this phase of a country’s development between institution strengthening/building and practical ways in which the majority of citizens, especially the most vulnerable, can begin to feel the practical value of this strategy through improvements in their well-being. This is important for generating and maintaining political support for the policy.