On July 11th, the London Summit announced it had raised enough money to meet the family planning needs of an additional 120 million women in the world’s poorest 69 countries. The Summit hosts – the UK government and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation – should be very happy with this accomplishment. Despite targets being set by a range of high level international commitments, including the International Conference on Population and Development and the Millennium Development Goals, the percent of official development assistance allocated to family planning has been spiraling downwards for more than a decade – falling from 55% of all donor funding for population and development activities[1] in 1995 to just 7% by 2009.

What has proven to be one of the most politically sensitive development topics now appears to be making a comeback, and if the plethora of international research is anything to go by, this will have very real benefits for women, children, families, communities, economies and the environment.

Whilst this achievement should be celebrated, it is disappointing to note that a majority of Pacific Island Countries (PICs) have missed out. This appears to be the result of the methodology used to determine which countries would be targeted by the Summit. Using World Bank data, those countries falling on or under a per capita gross national income (GNI) threshold of USD $2,500 in 2010 were included. Most PICs either fall just above this threshold, or the World Bank lacked data on their GNI per capita – a painful consequence and reminder of the need for increased availability of data and funding for Pacific research.

Of the 69 countries that fall under this threshold and are therefore deemed to be the ‘world’s poorest’, only two are from the Pacific – Papua New Guinea and Solomon Islands. From a purely numbers based perspective, the inclusion of these two countries is good news as together they likely account for around 90% of the region’s unmet need for family planning.

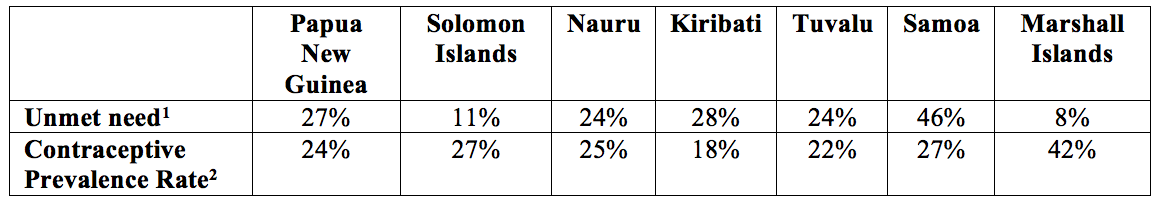

However, as has been said repeatedly by so many before, family planning is not about numbers, it is about human rights. In particular, the right of all women and couples to choose the number, timing and spacing of their children. Unfortunately, the available data tells us that the realisation of this right is not just a challenge in Papua New Guinea and Solomon Islands, but right across the region (table 1).

Unmet need for family planning and modern contraceptive prevalence rates in selected Pacific Island Countries

Source: statistics extracted from various demographic and health surveys available here.

Source: statistics extracted from various demographic and health surveys available here.

1: A women is described as having an unmet need for family planning if she is between the ages of 15-49, married or in a union and wants to avoid a pregnancy but is not using a modern form of contraception.

2: The contraceptive prevalence rate is the percent of all women aged 15-49 who are married or in union and who are using a modern form of contraception. The average CPR for less developed countries is estimated at 57%

Whilst most PICs missed out being explicitly targeted, the Summit does nevertheless provide the region as a whole with a unique and rare opportunity to capitalise on family planning’s sudden and dramatic return to visibility on the global development agenda. In the wake of the Summit, now is the time for regional advocates to step up calls for Pacific Island Governments and regional donors to be more accountable to the sexual and reproductive health and rights of the region’s peoples.

The timing is good for other reasons too. The Burnet Institute in cooperation with Family Planning International, have just released the preliminary findings of two cost benefit analyses of meeting the unmet need for family planning in Vanuatu and Solomon Islands. The results present regional donors and governments with a strong reaffirmation of family planning’s value as a highly effective and cost efficient development intervention. Better yet, for the first time they do so within the unique context of the Pacific, reducing the need for policy makers to rely on cost benefit data from overseas and building the region’s own evidence base for supporting family planning.

For too long, political sensitivities, a lack of quality family planning data, high transaction costs and the relative invisibility of the region have led to the severe neglect of Pacific family planning programmes – receiving just 0.03% of all the region’s aid over the last decade. If the region’s leaders and donors are truly committed to advancing development in the Pacific, they can no longer ignore the evidence of family planning’s value.

In particular, Australia and New Zealand, as two of the Pacific’s most important donors will need to play a key role in transferring the Summit’s momentum into reviving family planning programs in the region. Having been a strong supporter of the Summit and having increased its financial commitment to family planning, Australia appears to be leading the way. However, as of yet there is no clear indication that a reasonable portion of this new commitment will make its way to the provision of commodities, information, services and building of capacity in the Pacific. Across the ditch increased efforts are needed to pull New Zealand into engaging with the international push for improved financing of family planning in the Pacific and globally. New Zealand – usually a strong advocate of human rights – had no representation at the Summit and has so far made no financial commitment to the Summit.

There is much more work still to be done if universal access to family planning is to be achieved across the region. The Summit’s spotlight on family planning has created a rare opportunity, one that may not last long and one that the Pacific and the rest of the world can ill afford to let slip away.

Sean Mackesy-Buckley is a researcher for Family Planning International, a NGO based in New Zealand that is focused on advancing SRHR in the Pacific

[1] Under the International Conference on Population and Development’s Program of Action, developed countries agreed to meet up to one third of the cost of delivering a package of sexual and reproductive health services by 2015. This package included services for: 1) family planning, 2) sexually transmissible infections (including HIV), 3) reproductive health, and 4) related research.

Leave a Comment