It’s been a challenging year for Pacific labour mobility. With the onset of COVID-19, borders in the region were quick to shut. And, have largely remained so. Migrant flows ground to a halt with closure of the Australian border in March 2020. While closures have helped to curb the spread of COVID-19 in the region, they have wrought havoc on Australia’s labour market. Balancing the health impacts of the pandemic with the economic implications of the response (border closures, restrictions on domestic mobility) has been a tricky business.

News headlines have been littered for months with stories of labour shortages or challenges in meeting labour demand. Throughput production in the meat processing industry is down, horticultural production is forecast to drop by up to as much as 17 per cent, and hospitality and tourism sectors have had to limit capacity or reduce opening hours [$]. Recovery, following significant strain for much of 2020, is being hindered.

Temporary migrants who often fill workforce gaps (working holiday makers, international students) have left the country or have not been able to come. Labour demand is unmet in a range of industries, despite government incentives (of a scale unseen before) to get Australians into work. Domestic unemployment dropped to 5.6 per cent in March. Beyond domestic incentives, the government has positioned Pacific labour mobility front and centre as a way of addressing unmet labour demand. With few COVID-19 cases in the region, yet significant economic cost, the restart of labour mobility has been critical for both Australia and its Pacific neighbours.

The Pacific Labour Scheme (PLS) is the Australian government’s extended temporary migration scheme for the Pacific and is explicitly designed to support labour shortages in rural and regional areas in Australia, in any industry. Along with the complementary Seasonal Worker Programme (SWP), the PLS is one of the few options through which employers can currently source migrant labour. The Australian government announced a restart to the SWP and PLS in August 2020 and by early November, all ten participating PLS countries had opted back into the scheme.

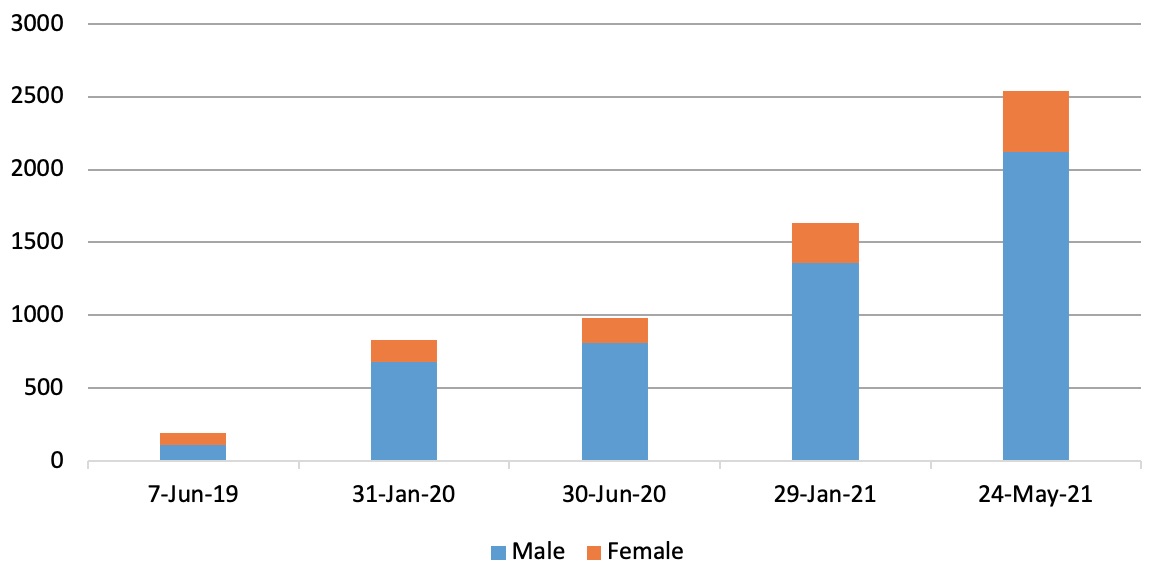

At the end of January 2021, a total of 1,633 were employed in Australia on the PLS (along with 98 in quarantine in Australia awaiting clearance). In the 12 months to end January 2021, the PLS almost doubled in size (96.7 per cent growth) on the previous 12-month period, with 80.8 per cent of growth in the period June 2020 to January 2021. Not bad, considering international borders were closed and the scheme was suspended for half of the year. This growth has continued too, with 2,537 reported on the scheme at 24 May 2021.

Figure 1: Total PLS workers

Despite what appears to be steady growth, it has not been business-as-usual for the PLS during COVID-19.

Participants on the scheme who were in Australia when lockdowns came into effect have had their stays (and visas) extended, and were unable to return home due to ongoing border closures in the Pacific, quarantine capacity constraints or a lack of flights. Longer stays and COVID-19 impacts on business have seen changes to participants’ hours and earnings, work arrangements, and even employer. For those new arrivals, specific quarantine arrangements have been established, ranging from on-farm quarantine to pre-travel quarantine (see the Victoria-Tasmania deal [$], South Australia’s Paringa facility, pre-travel quarantine pilot).

The way in which the scheme operates, and its oversight, has had to change as a result as well. Concessions allowing greater worker portability have been made. Stand down of workers due to industry down turns, seasonal changes (particularly in meat), or reduced hours (workers are guaranteed minimum hours on the scheme) have resulted in redeployment of workers across employers and industries (facilitated by the Pacific Labour Facility (PLF)). Introduction of a new Deed of Agreement for participating employers in January 2020 was well-timed in retrospect too, pushing greater responsibility for pastoral care of workers to employers. Arguably a necessary step, given questions around scalability of the approach, and particularly when coupled with the added challenges posed by COVID-19.

Growth (and resumption of recruitment under the scheme) has been limited to select industries. There may be a number of reasons for this. The PLF issued a temporary hold on assessment and acceptance of new employers into the scheme, with existing applications and employers prioritised. And then, there are all of those challenges the Australian public are well versed in – flight availability, quarantine capacity, and different rules and arrangements by state/territory (and the resultant state-federal tussles and delays).

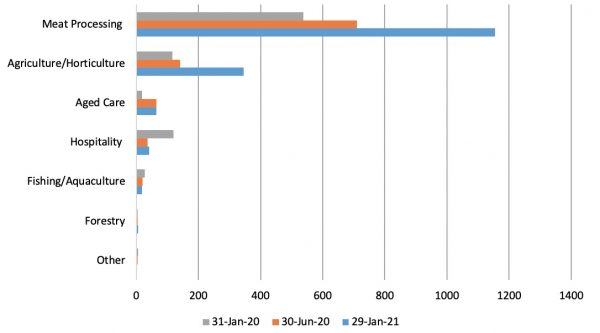

The meat processing industry continues to dominate the scheme, employing 71 per cent of all scheme participants (at end January 2021). Interestingly however, the twelve months to 29 January 2021, saw a 196 per cent growth in agriculture/horticulture participation, to overtake the hospitality industry (previously equal second) as the scheme’s second largest industry (with a 21 per cent share).

The growth in the meat processing industry is perhaps to be expected. Growth in agriculture/horticulture industry participation is telling. According to information released by the PLF (no longer available online), 68 per cent of businesses that showed interest in engaging with the scheme since March 2020 have been in the agriculture and horticulture sectors.

Comparisons with participation in the SWP over the same period could be instructive. Labour shortage woes in the horticulture industry have been well publicised and persist, and the warning bells for the longer-term impacts of a lack of grower confidence in securing labour are being sounded. Growers have been reported to be cutting back production, planting less, or leaving the land. A large selling point of the PLS has been the stability it affords employers. With fewer backpackers and diversification in the industry, can we expect to see more non-seasonal opportunities for Pacific Islanders in this sector? These early figures certainly suggest so.

Figure 2: PLS workers by industry, over time

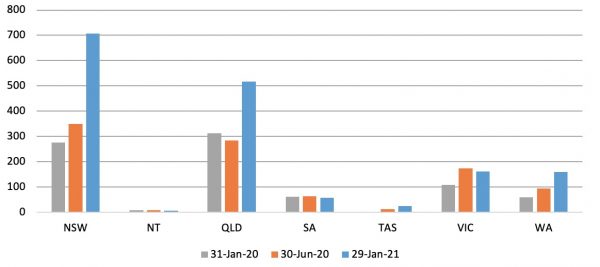

Participation in the scheme jumped by more than 40 per cent in New South Wales, Queensland, Tasmania and Western Australia in the seven months to end January 2021.

Figure 3: PLS workers by state, over time

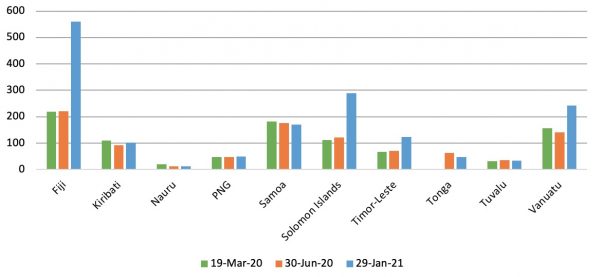

Just as state/territory PLS participation reflects, to a large degree, management arrangements, capacity to respond to COVID-19 and its impacts, and perceptions of risk, so too does country participation. Two thirds of all scheme participants, at the end of January 2021, were from Fiji (561), Solomon Islands (290) or Vanuatu (243). Pre-COVID-19, Fiji, Samoa and Vanuatu were the dominant three sending countries, with a 59 per cent share (19 March 2020).

Growth in Fiji’s and Solomon Islands’ participation is particularly strong. Fiji’s participation in the scheme has jumped from a 23 per cent share pre-COVID-19 to a third of all PLS workers (34 per cent) at 29 January 2021. Samoa’s share has dropped from 18 to 10 per cent, while Solomon Islands’ share has grown from 12 to 18 per cent.

Figure 4: PLS workers by country

Despite being a late comer to the scheme, joining in April 2019, Fiji now dominates. The first PLS workers to mobilise following suspension of the schemes arrived on 24 November from Fiji, for work in a meat processing plant in New South Wales.

A newly announced pre-travel quarantine pilot that allows workers to quarantine in the Pacific, where resourcing and quarantine capacity permit, before travelling to Australia has the potential to see more rapid growth over the coming months, particularly from Fiji (although the current outbreak does raise concerns) and Vanuatu. States/territories need to opt in though and so far only South Australia has.

The scheme’s poor gender balance is one of the few constants. Female participation in the scheme continues to drop as a proportion of total worker numbers. After a promising blip in March 2020, where female participation hit 20 per cent, it dropped again to 16.6 per cent at end of January 2021 where it remains. With the meat processing industry dominating the scheme, this is unsurprising – only 9 per cent of industry participants are female (at January 2021).

Whether these trends hold over time remains to be seen. With no significant changes to Australia’s border closures forecast until mid-2022, it will be interesting to see how participation in the scheme develops.

NB: Data are from the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. Data quoted for 30 June 2020 and 29 January 2021 are for participants ‘currently employed in Australia’. Data for January 2021 are for ‘visas issued/currently in Australia’ and may not be strictly comparable.

Why are workers from PNG so under- represented in the Pacific Labour Scheme?

Hi John,

While there are some additional aspects of the PLS that might impact thinking about this question, the main reasons are generally similar to why PNG is also not particularly well represented in the SWP. Richard and Stephen look at this in their big SWP governance report here

https://devpolicy.org/publications/reports/Governance_SWP_2020_WEB.pdf

You might also be interested to join this presentation this month

https://devpolicy.org/events/event/8000-seasonal-workers-by-2025-from-png-20211117/

I understand both PNG and Australia are working hard to increase PNG participation in both schemes.

Best wishes,

Ryan

Hi Holly how long does it take for the recruitment process to take ?

Thank you Holly. I really enjoyed this article. John

Primarily the Meat Processing Industry clearly has identified and addressed the labour shortage and good on them for opting into the excellent PLS program.

However, somewhat surprising is that a number of SWP absconders are finding themselves in that industry, and as photos that I have reveal, even those who have absconded and have no work rights in Australia.

The lure of advertisements for anyone on a raft of visas, including the 408, where offers of relocation fees and bonuses are attractive, even though technically an SWP (or PLS) worker on the 408 or 403 cannot abscond and be employed anywhere other than by the sponsoring employer, without that sponsor’s and DESE’s approval.

The concept of in-country quarantining is commendable, but one still wonders why covid-free countries like Vanuatu, Solomons (? maybe one or two cases) and Samoa even need to have quarantining in the first place, given that NZ and AU have a “bubble” and even interstate travellers can still cross the VIC border currently with their outbreak that far exceeds the total number of any of those countries cases, ever.