The news recently broke that Antonio Guterres, former prime minister of Portugal and head of the UN’s refugee agency, will be the next Secretary-General of the United Nations, after a UN leadership race that was starting to feel as long as the US presidential race (though the UN race was thankfully, at least most of the time, rather less acerbic).

Another high-profile human resources announcement came hot on the heels of Guterres’ appointment. Last Friday the UN officially launched a new honorary ambassador to champion the cause of women’s empowerment. She’s a globally recognised feminist and queer figure with considerable star power.

Her name? Wonder Woman.

Yes, the 75-year-old comic book character. Yes, the one who was created by a man. Yes, the one who came from an all-female nation (what happened to #HeforShe?) designed “to allegorise the safety and security of the home where women thrived”. The fictional character.

The irony of this pick was clearly not lost on The New York Times, whose initial article on the appointment was headlined ‘U.N. picks powerful feminist (Wonder Woman) for visible job (mascot)’. The appointment spurred a barrage of think pieces and op-eds, and has certainly raised the ire of some UN staff, who started an online petition against the appointment and staged a silent protest at the launch.

According to the UN outreach director quoted by the Times, Wonder Woman will appear on the UN’s various social media platforms to spread messages about women’s empowerment, gender-based violence, and other global development issues predominantly affecting women and girls.

All very worthy causes, of course. But the choice of a fictional character to promote them strikes as laughably quirky at best, and downright patronising at worst.

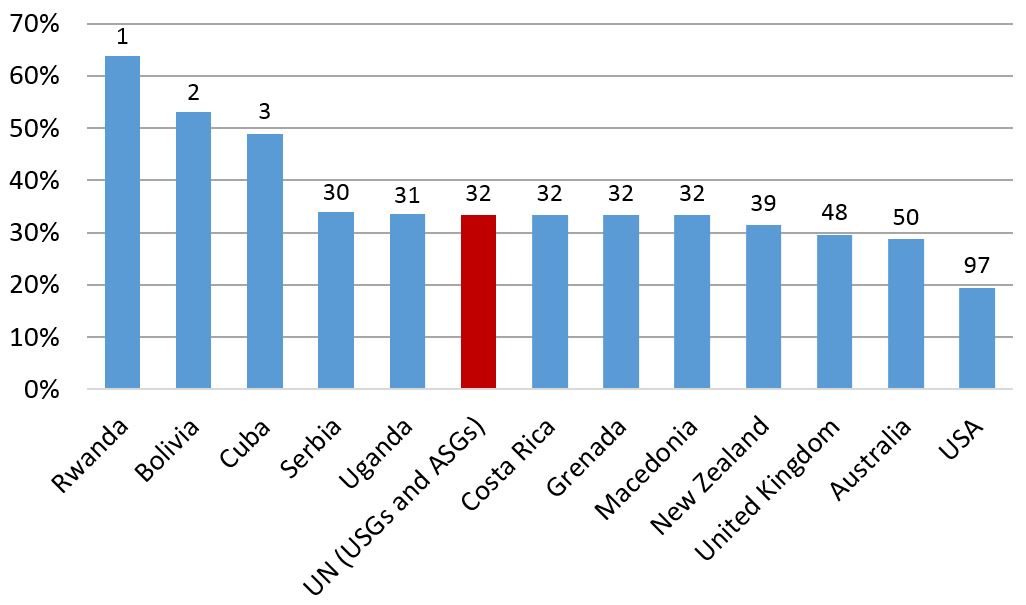

As has previously been noted on this blog and elsewhere, the UN system continues to face very real gender inequality problems. No woman has ever led the UN – despite there being seven impressive female candidates vying for the top job ahead of the most recent appointment – and women remain underrepresented in UN leadership roles. Though it committed to achieving gender parity in senior roles two decades ago, according to a July 2016 staff list just 26% of the UN’s 96 under-secretaries-general were female; at the next level down, 39% (36 of 128) of assistant-secretaries-general were female. In 2015 92% of staff appointed at the most senior (under-secretary-general) level within the UN were men.

If the combined staff in these two senior levels made up a parliament, the UN would rank in 32nd place globally on women’s representation, alongside Costa Rica, Grenada, and Macedonia (Figure 1). Not bad, and ahead of Australia (28.7%) and the US (a dismal 19.4%), but not exactly leading by example. So beyond appointing honorary standard-bearers for the cause of women’s empowerment, the UN could first and foremost focus on empowering more women within its own bureaucracy.

Figure 1: Percent female representatives in lower or single house (selected countries)

Source: Inter-Parliamentary Union (current 1 Sept 2016). Data labels show each country’s global ranking.

This is not to say that honorary standard-bearers can’t be a valuable tool in the UN’s advocacy arsenal. Celebrity or ‘goodwill ambassadors’, for example, are generally regarded as a useful way of reaching people who are not normally engaged with global development issues. Pop culture and anniversaries can also create good communication products – a successful example from earlier this year was a remake of the Spice Girls’ ‘Wannabe’ on the song’s 20th anniversary to promote SDG5. But the effectiveness of honorary ambassadors depends a lot on a) who they are and b) how they are deployed. Will Wonder Woman’s presence be limited to social media? And how will the messaging tie in with her ethos and story? A new blockbuster Wonder Woman film is set to be released in 2017 – will the actress who portrays her, Gal Gadot, make appearances or advocate on behalf of women and girls? Will there be calls for public participation and engagement, like we saw in the Spice Girls campaign?

This is also not the first time that the UN has turned to fictional characters to raise awareness. Presumably, if the UN is spending time and effort promoting such honorary ambassadorships, any formal evaluations of the impact of Winnie the Pooh, Tinker Bell, or the Red the Angry Bird’s tenures must have been favourable. But equally, the causes that these prior fictional ambassadors represented – International Day of Friendship, children’s environmental awareness, and the International Day of Happiness – seem rather lightweight relative to the issues of women’s empowerment and gender-based violence. If, as has been suggested, the use of celebrity ambassadors can lead to a ‘trivialisation’ of the cause they seek to promote, what effect does employing fictional celebrities as ambassadors have?

Even if deployed effectively, there will always be limits to what celebrity ambassadors, fictional or not, can do and who they can reach. To that end, the choice of a cartoon character as honorary ambassador neglects the many real life ‘wonder women’ and girls who have taken the floor at the UN, taken world leaders to task, and passionately argued for tangible and real change.

At the 1992 Rio Earth Summit, then 12-year-old Severn Cullis-Suzuki of Canada, who had started an environmental organisation with her friends at the age of nine and fundraised to attend the Summit, delivered an impassioned and highly memorable plea to leaders to act on issues of environmental degradation.

In 1995, the hopefully soon-to-be first female president of the United States spoke at the Beijing Conference on Women about the need for gender equality to be something that we must progress together, both women and men.

In recent years, we’ve of course had the inspirational Malala Yousafzai and famous faces like Emma Watson championing gender equality and access to education for girls. (Real life celebrity ambassadors, such as Watson and Angelina Jolie, can speak to the causes they are passionate about and the inequalities that they themselves see – fictional ambassadors perhaps do not have this same power).

And there’s also a growing number of emerging feminist voices from countries around the world finding a platform, such as Aya Chebbi, who spoke at CSW59 last year, and Marshallese poet Kathy Jetnil-Kijiner, who spoke at the 2014 Climate Leaders Summit.

There are also the many, many other women who are yet to have their voices and stories heard on an international stage, but who continue to push for change and make massive contributions to their countries, communities and families – and who may, therefore, have greater reach and more immediate tangibility within their countries and cultures than Wonder Woman will. Unlike Wonder Woman, they’ve also come from the real world where men and women co-exist, and where structural gender inequalities persist.

Why celebrate a cartoon character when there are so many real life women heroes (or, should we say, sheroes)? And why resort to tokenism via an online mascot when there are so many avenues for real and meaningful change left for the UN to pursue, both within its own halls and in the wider world?

It’s 2016. Gender equality shouldn’t need to draw on fictional characters to find a message. If Wonder Woman can attract some attention to gender equality among the noise (and abuse) online, perhaps that’s OK, but the real women of the real world need real power — not just a superhuman mascot to cheer for them.

Camilla Burkot and Ashlee Betteridge are Research Officers at the Development Policy Centre.

When Camilla and I were Googling for this post we also found some miscellaneous Wonder Woman facts and analysis that others might find interesting.

We didn’t want to go on a tangent so I’m just sharing some of them here in the comments.

Wonder Woman: Feminist Icon, Feminist Failure, or Both? – this is an interesting article with some of the history and different perspectives, particularly on the worldview of Wonder Woman’s creator

“[Comic book historian] Hanley’s curiosity over Wonder Woman’s curious career begins with her curious creator, writer and psychologist William Moulton Marston. Marston “wanted to impart to his readers a specific message about female superiority,” Hanley writes. Marston’s feminism didn’t hold that men and women were equal. Instead, he believed that women were superior and could bring about a more just and peaceful society than what men had achieved so far, especially in the midst of World War II. Wonder Woman’s women-only homeland of Themyscira thus became a utopian ideal. In the context of wartime America, Wonder Woman became “a superpowered Rosie the Riveter, constantly encouraging women to join the auxiliary forces or get a wartime job,” Hanley argues. While Wonder Woman inspired women to realize their full potential, she also prepared young boys reading the comics for the coming matriarchy, which Marston was devoutly believed would come after the war.”

But…

“Marston’s worldview came with complications, particularly a connoisseur’s eye for bondage, which went far beyond just the heroine’s “golden lasso of truth.” “For Marston,” Hanley defends, “bondage was about submission, not just sexually but in every aspect of life.” For the female utopia to happen, men must submit control, but everyone must submit individual desires to the greater goals of society.”

Also, if you like vintage comic book artwork, there’s some selected feminist panels from Wonder Woman cartoons in these posts here and here, and some arguments backing up her feminist status.

And it’s interesting how the UN has glossed over her being a LGBTI icon, in typical UN style. There’s a lot online about that as well.

The suitability or otherwise of Wonder Woman is only part of the issue. International celebrity ambassadors were novel once, but not any more. Barely a day goes by without some famous person in logo cap and t-shirt weeping into their cornflakes about the cause they have just embraced. Although they are billed as having international reach, many are barely known outside the western world.

Regional and national celebrities may provide a more authentic voice for their cause. Here’s a long list from UNICEF of their ambassadors in various places.

This article from 2011 looks at the wider debate about ambassadors.

While this 2006 UN report [pdf] makes recommendations about the future of use of goodwill ambassadors — it is unclear what suggestions, if any, were acted on.

Thanks Wendy (and sorry for the delay in getting your comment up, our spam filter is sometimes a little overzealous).

I’m not entirely opposed to hijacking pop culture/celebrity to help communicate a socially beneficial message, as long as it doesn’t compromise the message or come at a big cost. And as long as it is done really well and effectively, which as those reports show, is often not the case.

From a comms standpoint, I think the Wonder Woman appointment comes with a risk of confusing the UN’s already kind of fuzzy gender equality messaging – recently it was all #HeforShe, which I always found a bit patronising and vague but I at least kind of understood what they were trying to do with it (even if the execution was off). Now it’s about a woman who comes from an all woman planet and who has been both sexualised and objectified by men throughout history but on the other hand has at times espoused a very hardline feminist message that could be seen by the overly sensitive as ‘anti-male’. It’s all just really confusing from a messaging point of view. Who are they trying to communicate with and mobilise with this campaign? Which version of Wonder Woman is their ambassador (she’s had many iterations throughout history)? Is empowerment about equality and partnership between men and women, or is it about women becoming dominant? Such messy messaging.

So I oppose this one, but not all. But a big communications question for me in using celebrity/icons would be – whose pop culture do they represent? I think you are spot on about needing to look at regional and national celebrities if you are going to get messages to have traction in particular countries or regions. There is a real dominance of American/Western celebrities on the books as ambassadors and Wonder Woman is no exception. Yes, some of these celebs are truly global, but I completely agree that there is a real need to look at how they play with certain audiences.

I’m not convinced of the need to call these people ‘ambassadors’ though. I think that’s where this really sunk. Sure, if there is a good comms and messaging strategy, give some Wonder Woman related tweets a go and tie it in to the anniversary and the movie. But don’t call her an ‘honorary ambassador for women’s empowerment’ – that’s going to annoy real women who are tired of living up to impossible standards and pressures, let alone fictional superhero ones.

It does seem really trivial to appoint someone who has superhuman powers to be an ambassador for an issue that includes gender violence. What, are women supposed to just get superpowers and kapow bang whoosh their way out of violent situations? It’s like the UN think that women just need more inspiration to be powerful, instead of actual structural change.

Ashlee, Camilla

It is so good you wrote this yet what a shame it ever needed to be written!

While I observe your comment in other media as this being a “rant” I think otherwise…it is an articulate expression of your frustration (on behalf of others, the many) of the idiocy of an organisation that should know better.

Maybe there is a method in their madness as you observe that raising the vibration on conversations is good – but I agree that of all the ways in which this important global issue could be prioritised, this seems polar from the better options.

I also comment, with some embarrassment, that as a male my voice was slow to condemn – no excuse, just slow.

Thank you for not being silent.

M