Papua New Guinea’s law and justice sector is set to receive a 22 per cent increase in the country’s 2019 budget. Treasurer Charles Abel says this demonstrates the government’s commitment to the sector, and to addressing crime and corruption (see this PDF). Look beyond this headline figure, however, and the rise is not so impressive. Indeed, it doesn’t even make up for recent years of budget cuts: economist Paul Flanagan shows that with the recent increase, the sector will still have suffered a funding cut of 17 per cent relative to 2015.

Focusing on the law and justice sector also overlooks organisations specifically tasked with addressing corruption. Most of the 13 organisations making up the sector – including the Department of Justice and Attorney General, Royal PNG Constabulary, Department of Defence, National Judiciary Services and Correctional Institute Services – are not primarily anti-corruption agencies, although they do help address corruption. In this blog, we home in on what the 2019 budget means for dedicated anti-corruption agencies. We follow up our previous analysis (see here and here) by examining the 2019 allocations for the Ombudsman Commission, the National Fraud and Anti-corruption Directorate, Taskforce Sweep (and its replacement: the proposed Independent Commission Against Corruption), the Auditor-General’s Office, and the Financial Analysis and Supervision Unit (previously known as the Financial Intelligence Unit). We also include funding for PNG’s relatively new Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI).

This blog draws from analysis that tracks budget allocations and spending for each of these organisations since 2008 (available here).

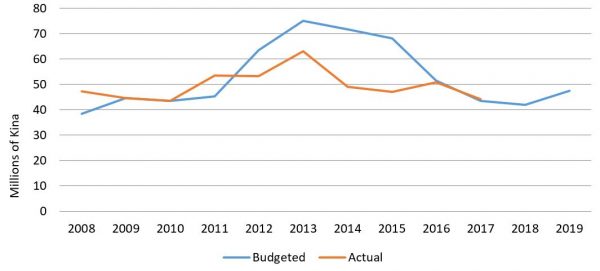

First, the good news. The government allocated the one anti-corruption organisation included in the 13 agencies that make up the law and justice sector, the Ombudsman Commission, an additional 23 per cent of funding compared to 2018. The Auditor General also received a small increase over last year — its funding increased 7 per cent: from 17.7 million to 18.9 million kina (in 2018 prices). These increases mean that combined funding for the six anti-corruption agencies we examine increased, in real terms (that is, allowing for inflation), from 42 to 48 million kina between 2018 and 2019. In addition, the funding gap between how much the government budgets for anti-corruption agencies and how much they received, remains closed. In fact, in 2017, anti-corruption agencies received two percent more than their allocations. As Figure 1 demonstrates, this is a vast improvement on years gone by, even though anti-corruption agencies are not faring as well as other areas of the budget.

Figure 1: Actual spending vs budgeted for whole budget and six anti-corruption organisations

That is where the good news ends.

Recent gains are not enough to make up for a history of cuts and underspending (see Figure 2). Between 2013 and 2019, the six anti-corruption organisations we examine saw their funding cut by 56 per cent: from 75 million to 48 million kina (in 2018 prices). Between 2008 and 2017, these organisations failed to receive 49 million kina that the government allocated for their operations.

Figure 2: Total anti-corruption allocations and spending 2008 – 2019 (2018 kina)

The bad news is compounded by the lack of funding for the much-anticipated Independent Commission Against Corruption (ICAC). It received only 400,000 kina, which is 100,000 kina less than last year. So don’t expect to see an ICAC in PNG anytime soon. While the Financial Analysis and Supervision Unit maintained funding of just under 300,000 kina between 2018 and 2019, it is well short of the almost 500,000 allocated in 2017. In addition, the EITI has had, in prices adjusted for inflation, its funding cut slightly from 2.7 million kina in 2018 to 2.6 million kina in 2019.

The most tragic anti-corruption agency has to be the Fraud Squad, which sits within the Royal PNG Constabulary (RPNGC), the country’s police force. While the RPNGC had a bump of 50 million kina – a 19 per cent increase – between 2018 and 2019, funding for the Fraud Squad will not make up for a history of significant cuts. Next year it is set to receive 640,000 kina (2018 prices), which is slightly less than 2018, and a full two-thirds lower than its 2016 allocation (see Figure 3). The agency that bravely but unsuccessfully led efforts to arrest Prime Minister Peter O’Neill over allegations of corruption has been reduced to a shadow of its former self.

Figure 3: Allocations and spending on Fraud Squad, 2008 – 2019 (2018 real kina)

With 1.3 million kina to spend on musicians and musical instruments, in 2019 the government allocated the police band more money than the Financial Analysis and Supervision Unit and the Fraud Squad combined. This continues a long-running trend: it was ABC journalist Liam Cochrane who in 2015 first pointed out that the PNG Government directed more funding to the police band than the Financial Analysis and Supervision Unit.

While it is a welcome relief that the government has tempered the savage cuts of previous budgets, the 2019 budget does not make up for years of shrinking anti-corruption budgets and underspending. Moreover, this budget leaves PNG’s most potent anti-corruption agencies under-funded and under-resourced, which is exactly what some of PNG’s political elites want.

Calculations for figures and graphs cited in this blog can be found here.

Thanks Amanda. The phones against corruption initiative is not captured in these figures as we focus on anti-corruption organisations funded by the national government. You are right, this initiative has had some wins, although there are challenges around scaling it up, as your and Colin Wiltshire’s fascinating discussion paper highlights.

Thank you Dr Grant Walton and Ms Husnia Hushang for a most interesting blog post, with clear analysis and helpful diagrams.

One very small project which has had some wins and which may not be captured in the budget figures you’ve analysed is the Phones against Corruption project.

For more information on Phones against Corruption, see here and here.

Amanda

Dr Amanda H A Watson

Lecturer

Australian National University