Labour mobility in the Pacific region has been recognised in recent years as a vital component of effective development in the Pacific. Yet little analysis has been conducted on those Pacific Islanders that have already made the leap to Australia. (By contrast there have been two major pieces of government funded research into the New Zealand context.)

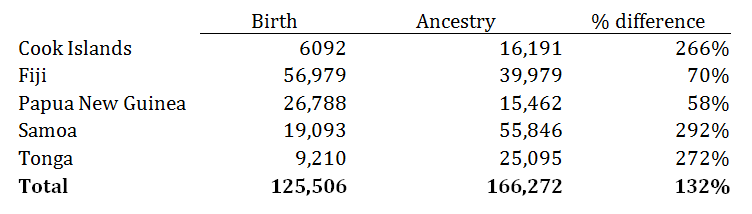

A natural starting point for analysis of this kind is the census. For my analysis I have opted to use the variable of ancestry as opposed to place of birth. Place of birth is the better indicator if you are interested in tracing individuals who are themselves migrants. Ancestry is a better indicator to assess overall stock of ethnic Pacific Islanders in Australia. It matters a lot because place of birth excludes the New Zealand migration pathway to Australia (see Samoa and Tonga), and includes a lot of people born in Pacific Island countries (e.g. Australians born in PNG) who do not identify as Pacific Islanders.

Pacific Islanders in Australia: ancestry vs. birth

Source: 2011 Australian Census.

Source: 2011 Australian Census.

Using this definition, Pacific Islanders in Australia still account for less than 1% of Australia’s total population. By contrast, New Zealand’s 2013 census shows people with Pacific Islander ancestry (not including Maori) made up 6.9% of the population.

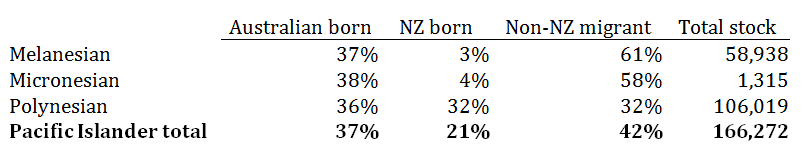

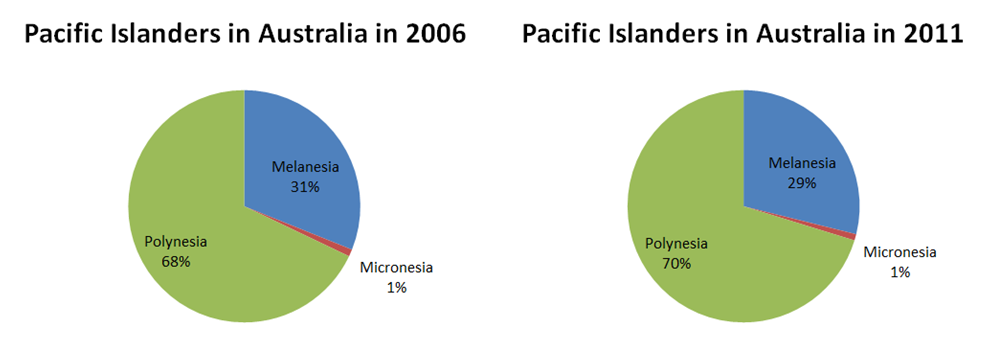

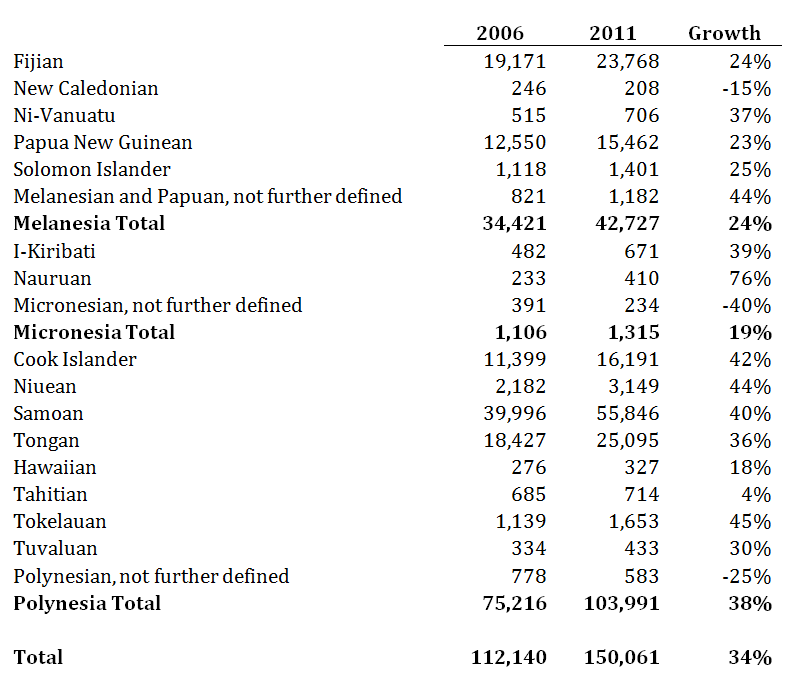

While the Pacific is not an important source of migrants to Australia, Australia is still an important migration destination for some Pacific Islands. Of the 166,272 Pacific Islanders in Australia, 35% are from Melanesia, 64% from Polynesia and 1% from Micronesia. (A detailed table with the number of people from each Pacific state can be found at the end of this post.) We can compare these numbers with those of the populations of these three regions. The ratio of Melanesians in Australia to Melanesians in Melanesia is 0.7%; the equivalent ratio for Polynesia is 15.9%; and for Micronesia 0.2%.

Why? Why are there more Cook Islanders in Australia than Papua New Guineans, when the latter has more than 430 times the population of the former and is our former colony? Why more Nieuans than Solomon Islanders, when the latter has more than 360 times the population of the former, and has far closer links with Australia.

The explanation is simple: the New Zealand route. As the table below shows, one third of Australian Pacific Islanders who identify as Polynesian were born in New Zealand. This is because many Polynesian countries have migration access to New Zealand, and thus Australia via our open border policy with New Zealand.

Sub-regional breakdown of Pacific Islander migrants

Source: 2011 Australian Census.

Source: 2011 Australian Census.

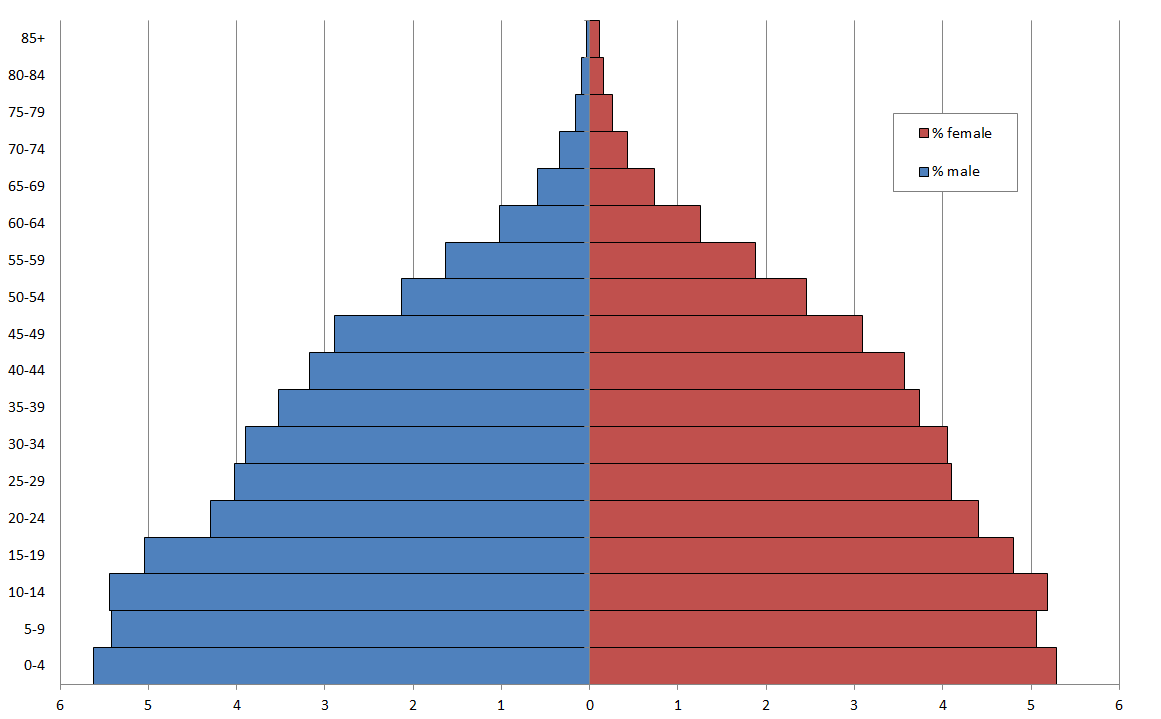

Another component of the story of Pacific Islanders in Australia is the young age structure of the Pacific population here. 42% of all people in Australia with Pacific ancestry are under 20 years old.

Population pyramid for people in Australia with Pacific ancestry

Source: 2011 Australian Census.

Source: 2011 Australian Census.

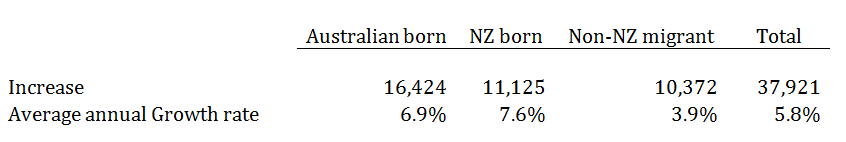

How is the population of Pacific migrants changing over time? The total growth of Pacific Islanders in Australia reflects an annual average growth rate of close to 6%. This is more than three times faster than the total Australian population growth rate of 1.6% in 2012. If this growth continued for 30 years, the Pacific population would be close to 3% of Australia’s total population, compared to under 1% today.

This rapid growth is mainly due to growth in the number of Australian-born and NZ-born Pacific Islanders. The number of Pacific Islanders directly migrating to Australia from anywhere but New Zealand is growing at half the rate.

Growth rate of Pacific Islanders by place of birth, 2006-2011

Note: Growth rate analysis in this post does not include ‘Fijian Indians’ (who accounted for about 10% of the Pacific Island population in Australia as of 2011) as they were not included as an ancestry category in the 2006 census.

Note: Growth rate analysis in this post does not include ‘Fijian Indians’ (who accounted for about 10% of the Pacific Island population in Australia as of 2011) as they were not included as an ancestry category in the 2006 census.

Source: 2006 Australian Census and 2011 Australian Census.

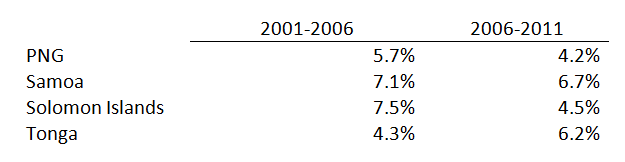

It is also interesting to look back over a longer period, though we can only do this for some countries.

Average annual growth rates from 2001 for select Pacific Islanders in Australia

Source: Appleyard and Stahl 2007, 2006 Australian Census and 2011 Australian Census.

Source: Appleyard and Stahl 2007, 2006 Australian Census and 2011 Australian Census.

As can be seen, the growth rate for migrants from both PNG and the Solomon Islands has fallen over the past ten years, while Tonga’s has increased and Samoa’s has remained the highest in the region. The increase in the number of Samoans living in Australia over the last decade (almost 28,000) is almost twice the total number of Papua New Guineans living in Australia (15,500). As a result, the proportion of Polynesians among all Pacific Islanders is actually growing, and the proportion of Melanesians is shrinking.

Source: 2006 Australian Census and 2011 Australian Census.

Source: 2006 Australian Census and 2011 Australian Census.

PNG, Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, Kiribati, Nauru and Tuvalu. These are the six countries in the Pacific that have the fewest labour mobility opportunities, and are generally the poorest as well. Their share of the Pacific population in Australia has fallen over the last five years from 13.6% to 12.7%. The increase in the stock of migrants from these six countries over the last five years has been 770 a year on average. That’s a drop in the ocean.

We need to get serious about offering labour mobility opportunities to those parts of the Pacific that most need it. New Zealand has been doing this for its former colony, Samoa, and other Polynesian countries over the last half-century. We have a long way to go to catch up.

Jonathan Pryke is a Research Officer at the Development Policy Centre. This post is based on his presentation at the 2014 Pacific Update. Presentation slides are available here. Read the second post in this two part series here.

Growth in Pacific Islanders in Australia

Notes and sources: 2006 Australian Census and 2011 Australian Census. This table and the pie chart do not include ‘Fijian Indians’ as they were not included as a demographic category in the 2006 census.

Notes and sources: 2006 Australian Census and 2011 Australian Census. This table and the pie chart do not include ‘Fijian Indians’ as they were not included as a demographic category in the 2006 census.

See here for an updated blog with 2016 census data.

Hi Jonathan,

Thankyou for a most informative and timely phenomenon. I was thinking about that in the context of the changing environments in the Pacific Islands and within the economies of these countries, and thought to myself that these changes in climate changes, the challenges in relationships domestically, the socio-economic woes of lack of health and education services and etc., are leading to little to nil productivity and employment opportunity.

Labour mobility is a sure way of helping many island countries with their people sending money back home which will end in time when communities as you have mentioned will grow in New Zealand and Australia.

It is interesting that you mention Melanesia, initially, laboour mobility to Australia from PNG happens where employment is secured. Where people have no land (where I come from) on the southern part of PNG, the young will opt for employment even in NZ and Australia. The seasonal fruit picking programme in New Zealand is one with those who worked in mining companies now working overseas. Not all of them, but it is the beginning of a trend which will grow because of the opportunities that exist there.

Land is abundant in Melanesia and thus opportunities are many however the Government needs to support more in terms of helping more with buy and sell, even markets in Australia and NZ and USA be more accommodating simply because if they are not, then China, India etc., will come to Melanesia to stay irrespective of ideology, political bias, religion, cultural affinities etc.. A man needs food and money to look after their families. If China can bring health services straight to the village, who is to ask what?

My thoughts…

Regards,

Alurigo

Hi Jonathan,

I’m Papua New Guinean and I’d have to agree with Del Ken. Moving back home after working abroad is the preference for us. With more experience gained abroad PNGeans can come back to the Corporate sector, the government or NGOs.

In addition, and that’s if you own land, traditionally, you are expected to come back and settle and claim it or else your descendents will have no inheritance and therefore be considered outsiders. Maintaining a connection to his land and culture is significant.

Hi Jonathan,

Coming from the Cook Islands, it’s striking the number of Cook Islanders living in Australia and New Zealand (around 60,000 in the latter alone). A key reason for this accessing better opportunity and wages through use of the New Zealand passport – the ultimate in Australasian labour mobility.

From my own research, the trend towards Australia has been a relatively recent one, with increasing numbers of Cook Islanders born in New Zealand now moving to Australia as part of a broader ‘go west’ drift. I suspect the growing income gap between Australia and New Zealand is to blame, as well as labour shortages in some industries, but I haven’t looked into the matter in any real detail*. For Cook Islanders anyway, community is of the utmost cultural importance, and the integrity of the family unit is highly valued (as it is in almost any culture). The NZ passport means that whole family units can move, and where a community forms others will follow in greater numbers. I therefore suspect that migration to Australia (for Cook Islanders anyway) will accelerate as the Australian-based communities grow. I also suspect that our Polynesian neighbours (Samoa and Tonga) have similar aspects to their culture, as demostrated in the large Polynesian communities living in Auckland and Hamilton.

James

*As an aside: this has significant ramifications for the tiny Cook Islands population (around 15,000), which is likely to continue to suffer drain across all labour types, not to mention the intergenerational issues of cultural degradation (for example: only a fraction of Cook Islanders born overseas (myself included) can speak Cook Island Maori).

Very useful to have this statistical analysis of Pacific Islanders in Australia. For the ancestry data, how are ASSI descendants from Vanuatu and Sols counted?

Hi Anna,

It is up to each respondent of the census to identify their own ancestry. ‘Australian South Sea Islanders’ is not identified as a variable in the census data so they may have identified as either Australian or ni-Vanuatu/Solomon Islander. Unfortunately it’s impossible to be more precise.

Regards,

Jonathan

Many thanks for sharing these stats on the status and trend of Pacific Islanders in Australia. This information is very important to people like me providing advices to government in terms of policy options for economic development.

Much appreciated

Mose

CTA, Office of the Prime Minister & Cabinet

Honiara

Hi Mose,

I’m glad my research is of use to you! And I hope it continues to be in the future, along with all of Devpolicy’s Pacific focused work.

Regards,

Jonathan

What about the cultural factor, for instance the melanesian culture is quite distinct from the polynesian, melanesians have the tendency to return to their country after living abroad for a number of years, this might influence the pattern of migration

Hi Del,

Ron Duncan actually raised the same point when I delivered my findings at the 2014 Pacific Update. Unfortunately this can’t be captured in census data, but would be an excellent topic for future (possibly survey based) research.

Jonathan