The challenge for growers in Australian horticulture is to find sufficient labour for the months of September 2020 to January 2021 to harvest the fruit and vegetables they have produced. The total estimated seasonal workforce needed for horticulture for the spring and summer harvest season ahead could be up to 40,000 workers, based on the previous demand for seasonal workers over that period. This overall estimate of demand is at the lower end because we do not know how many other casual workers were employed, or the number of Working Holiday Makers (WHM, or backpackers) who worked in horticulture but did not complete 88 days of specified work in regional Australia to obtain a second-year visa.

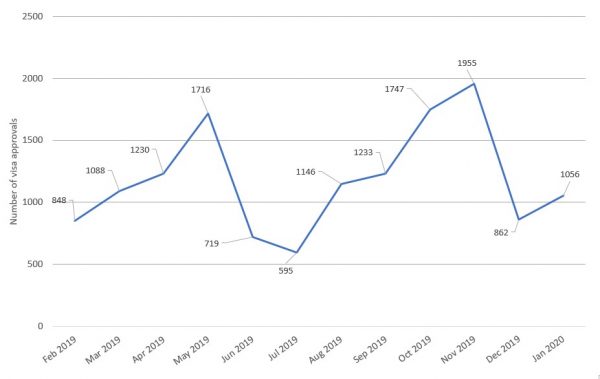

This estimate of demand is based on visa approvals for backpackers and Seasonal Worker Programme (SWP) workers from the Pacific and Timor-Leste. In the 12 months to the end of March 2020, just under 32,000 backpackers were granted a second-year visa after working for 88 days in agriculture. In addition, 7,999 SWP workers were granted visas to work in the period August 2019 to January 2020. As the figure below shows, the peak month for engaging SWP workers is November but their number increases from August.

Figure 1: SWP visa approvals February 2019 to January 2020

Where will this year’s seasonal workers come from? Department of Home Affairs data show that 6,761 SWP workers were in Australia at the end of January 2020. Some workers returned home once notice of border closures was made known. When international borders open again, many SWP workers now in Australia may well decide not to stay on, despite being happy to work under current conditions (and able to do so with the new visas they have been issued).

The visa statistics also suggest that the number of backpackers available to work in horticulture will be lower. The number of WHM visa holders in Australia at the end of March 2020 was 119,226, far below the 141,142 at the end of December 2019. Data on WHM visas granted show a drop from 50,566 to 36,841, comparing the third quarter for 2020 with the third quarter for 2019. The same trend is evident for the number of second visas granted, with 2,067 fewer visas approved in the first quarter of 2020 compared with the first quarter for the previous year.

Many backpackers may also decide to return home, with far fewer, if any, backpackers in a post-COVID world willing and able to come to replace them this year. On the other hand, some backpackers (and possibly some Australian citizens) will be ready to work on farms in the absence of city jobs. While there is a great deal of uncertainty, the best estimate is that, without fresh labour being imported, we will see major labour shortages on farms over the summer.

One way to assess the availability of local labour is for Harvest Trail to launch a public campaign to encourage domestic jobseekers willing to work in the forthcoming harvest season to register their interest. Jobseekers will need to prove that they are already resident in a designated regional local government area, have previous relevant work experience, and are willing to commit to the work and the hours required.

This prospect of an imminent major labour shortage in horticulture should also be encouraging the federal department responsible for employment to plan to ensure that a reliable supply of seasonal workers is available. However, little progress is being made, at least in terms of one reliable source of workers, namely those engaged through the SWP. The Department of Education, Skills and Employment (DESE) has told Approved Employers that they are not to submit recruitment plans until after international borders open again. This approach is guaranteed to ensure that new SWP workers are not in Australia for the start of the peak season. It takes time for up to 160 Approved Employers to develop and submit separate plans for recruitment, accommodation, and welfare and wellbeing, and for the seven SWP contract managers to approve them. There is also another at least six-week lag at best, due to the process of recruiting, vetting, briefing and sending workers to Australia.

A better approach would be for DESE to encourage Approved Employers to develop and submit recruitment plans as soon as possible, not least because this process will reveal critical information about growers’ own assessment of their demand for seasonal workers. Approved Employers are carrying the risk, so their assessment has to be taken as the best available. Plans can be approved subject to the resumption of travel.

The extended process required to navigate the managed pathway needs to commence now to ensure seasonal workers are on the farm for an August or September start.

Correction 18 June 2020: In the 12 months to the end of March 2020, the 32,000-odd backpackers who were granted a second-year visa, were granted the visa after working for 88 days in agriculture.

This post is part of the #COVID-19 and the Pacific series.

Definitely get unemployed to work there. Some say they will not enjoy the work, neither do half of australians going to work. Why should they sit on their backside and take taxpayers money for doing nothing. The government pay you until you find work not to find something you really like

I help my partner in Vanuatu who is an agent doing the recruitment, vetting and briefing mentioned in your excellent post. We are baffled by the lack of communication and planning that the situation warrants as we can see from both sides – the Approved Employers really need to plan their labour supplies and be equipped for all contingencies – and we know the workers are hanging on every word, every chance that they may be required in an instant to be work ready and leave. Vanuatu is one of the few countries in the world to be declared Covid-19 free and this could be a great positive for the farmers and the workers wanting to travel to Australia under the SWP. Especially as the SWP is under the umbrella of Australia’s aid to the Pacific and this particular country had relied on tourism, which is now of course completely in tatters due to border closures. The SWP is the perfect win-win for Vanuatu people and the Approved Employers who need this planning done now. I would hope maybe talks government to government may be the first step? Perhaps the planes going to collect the repatriating workers in the next couple of months can also deliver fresh workers at the same time….

I am samuel Toroitich from hardwork 32 years of age married with two twins and looking for work. I have a bit of an idea on farming – plz help get a job there.

The well documented attempts to use job seekers or youths in detention will not work. You are saddling farmers with mainly unwilling workers.

Thanks for this timely post Richard. All of us will pay a price in terms of increased cost of fruits and vegetables if farmers are unable to bring their produce to market. Of many great things about Australia is the steady supply of fresh produce – thanks to our farmers, retailers, and their workers. If the labour shortages on farms is not addressed soon then we will be paying higher prices for our green groceries; not just this year, but also next year.

Why can’t the Govt and horticulture industry associations get the unemployed people registered through Centrelink, for this work. Work and get paid, maybe incentivise with stay arrangements for the workers. There would be some farmers out there, who have innovated, to use labour at similar costs compared to WHMs. Any learnings from them could be used by the industry.

Great blog post Richard. I think you’re bang on.

In relation to WHM movements, new figures show by end of April 2020, the number was down to 98,000. This shows a quick downward trend from the start of 2020, indicating the shortage through until January 2021 could be very substantial.

This is a great time to move the youths in detention out to farms and work. They would learn about farming and also help out our farmers at the same time.

Just an idea for the shortage of staff.