If you’re going to ignore international norms, it’s always easier if someone else is ignoring them with you. Once, New Zealand helpfully provided Australia cover when it came to being a miserly aid donor. This is no longer the case. As Australia’s inflation-adjusted aid spend continues to slide, something odd has happened over the Tasman.

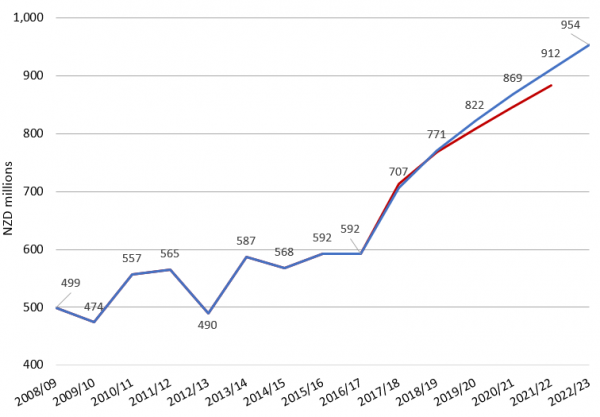

For a long time New Zealand’s aid budget moped around looking unimpressive. That’s all starting to change though. First, aid spending lurched up in 2016/17 as the aid program rushed accumulated under-spends out the door at the end of a three-year budget allocation. Then, in last year’s budget, thanks to the tenacious efforts of Foreign Minister Winston Peters, the aid budget was put on an ongoing upward trajectory. (Peters is leader of a smaller conservative/populist party that is part of New Zealand’s current centre-left governing coalition. Unfortunately, I don’t have an answer for Australian readers wondering why the leader of a nationalist party called New Zealand First would be willing to fight Treasury to get the aid budget increased.)

I have to confess I was part expecting to be disappointed by this year’s budget (New Zealand’s budget day is 30 May). I thought the aid program would be failing to spend the additional aid, or that the promised future increases of the last budget would have been rescinded somehow. I was wrong. Indeed, I actually was more than wrong. Not only does the aid program appear to be keeping up with spending increases, but the rate of budgeted increases in New Zealand aid has actually gone up since the last budget. Not massively, but an increase nevertheless.

The chart below compares promised aid spends from last year’s budget with promised aid spends in this year’s budget.

The 2018/19 and 2019/20 aid budgets compared (nominal)

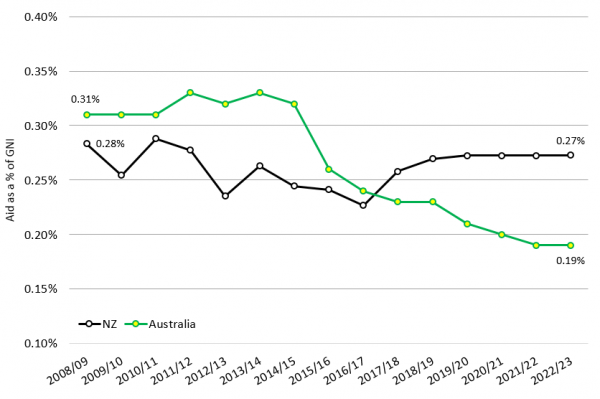

New Zealand’s economy is also growing. This means increases in aid as a share of GNI don’t look as impressive. But that brings me back to Australia. The following chart compares Australia and New Zealand. (Australian data come from Devpolicy’s Aid Tracker.)

Aid/GNI Australia and New Zealand compared

(Note: the aid budget is often talked of as being at, or soon to be at, 0.28% of GNI in New Zealand. I don’t know why my numbers differ from this claim. It may be because a very small share of New Zealand aid spending falls outside of “Vote ODA”, the central budget line for aid. Regardless, the difference is very small. A spreadsheet of my source data and calculations can be found here.)

New Zealand could be doing better, but it’s turned around years of decline. What’s more, Peters has talked about his desire to see the aid budget “closer to 0.35%” of GNI in coming years. Australia, on the other hand, is tumbling down into what Stephen Howes has called the “0.2 club”, a group of unimpressive OECD aid donors that are mostly much poorer than Australia. When I looked at this in-depth in 2017, I found the only countries wealthier than Australia that had lower aid/GNI ratios were the United States and Iceland. I also found that debt provided Australia with no excuse for giving so little, despite political rhetoric. Public debt in Australia is actually very low by OECD standards. All of the countries with worse aid/GNI ratios than Australia in 2017 were more indebted than Australia. (The only exception in 2017 was New Zealand, but obviously that’s no longer true.)

I’m not telling you any of this as a gloating New Zealander. For a start, I live in Australia, I own a home here and I pay taxes here. I feel part of the policy decisions Australia makes. What’s more, New Zealand is hardly immune to bad foreign policy. The same budget that saw the New Zealand government increase aid also saw it decide to waste $25 million (NZD) on preventing asylum seekers from arriving on boats. (I say waste because — unsurprisingly — the large, stormy Tasman Sea already serves as an effective impediment.) Also, as Jo Spratt has written, New Zealand needs to do more to improve aid quality.

Rather, I’m making the obvious point that if New Zealand can afford to increase its aid budget, Australia can too. And if Australia doesn’t, it’s going to start looking more and more like an outlier in coming years — a country that fails to conform with international norms of giving, even when it could easily afford to.

Thanks Croz, I hope all’s well with you. Terence

Hi Terence,

Great blog. I’ll be using some of your posts on mine, acknowledging the source, of course.

Best wishes,

Croz Walsh