Since the Coalition’s election in 2013, Australian government aid has changed significantly. AusAID, the government aid agency, has been fully integrated into the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) and there have been unprecedented cuts to the aid budget.

The 2015 Development Policy Centre Australian Aid Stakeholder Survey report, Australian aid: signs of risk [pdf], released today, shows the dramatic impact of these changes. The majority of aid stakeholders still think Australian government aid is effectively given, but they worry that the quality of Australian aid is getting worse. Our analysis points to particular areas of weakness and risk, and suggests policies that can be implemented to reverse the perceived decline.

We conducted the first ever Australian Aid Stakeholder Survey prior to the 2013 elections. The objective of the survey is to assess the state of Australian aid by gathering input from stakeholders – aid experts who work with it regularly and who have first-hand experience of its performance. The survey is run in two phases. The first targets senior managers from Australian aid NGOs and aid contracting companies. The second phase is publically accessible and open to a broader range of aid stakeholders.

In the second half of 2015 we repeated the survey, using the same methods and asking similar questions. This time, we attracted an even larger number of respondents: 461 in 2015 compared to 356 in 2013.

The 2015 survey contains some good news for the aid program. Foremost is that the majority of stakeholders — 61 per cent — believe that the aid program is effective or very effective. Nearly all those involved in implementing the Australian aid program still think their own aid projects are effective. Many stakeholders support the greater focus on the Asia-Pacific region, and most back the increased emphasis on aid for trade, although they suggest the government might have gone too far in this regard. Modest improvements in the area of aid management streamlining are suggested, and respondents also note that the problem of rapid turnover of aid program managers within AusAID/DFAT has eased slightly.

Foreign Minister Julie Bishop is widely seen as a champion for aid, and her emphasis on gender is clearly appreciated, though broader government support for aid is seen as lacking. Three-quarters of NGO stakeholders view political leadership as a weakness or a great weakness for the aid program, and over half of aid contractors feel the same way. The survey was almost entirely conducted prior to Steven Ciobo becoming Minister for International Development. His appointment is certainly a political positive for the aid program, but the treatment of aid in future budgets will probably be even more important in influencing further ratings of political leadership.

The survey also reveals some very worrying trends. Now it is 61 per cent, but two years ago 70 per cent of stakeholders rated the aid program as effective or very effective. Moreover, three-quarters of the aid experts we surveyed now think that its performance has become worse over the last two years. By stark contrast, in 2013, more than three-quarters thought the aid program had improved over the previous decade.

Figure notes: Responses from both phases of the survey were very similar, and both are covered in the survey report. For simplicity, graphs and numbers in this blog post relate to Phase I respondents (110 NGO and aid contractor staff).

This fall in perceived effectiveness is not surprising given the budget cuts. Respondents indicate clearly that the budget cuts have reduced effectiveness. We asked not only about overall effectiveness, but about things that matter for effectiveness – some 17 attributes in total, including funding predictability. It was viewed in 2013 as a strength of the aid program, but a lack of funding predictability is now viewed as the biggest weakness of the aid program out of all 17 attributes.

It would be a mistake to view this deterioration in perceived effectiveness as a temporary effect. Of course, for effective aid there shouldn’t be more budget cuts. (Worryingly, still more aid cuts are scheduled for the 2016–17 budget.) But most of the 17 aid program attributes showed declines rather than increases, and some declined a lot, turning from strengths into weaknesses. Reversing some of these steep declines will not be easy.

Figure notes: In both 2013 and 2015, respondents were asked to rate, as strengths or weaknesses, 17 attributes that are important for aid program effectiveness; 16 are shown in this figure (the 17th is ‘strength of political leadership’). The ratings are normalised from zero (great weakness) to one (great strength) with 0.5 being a neutral rating. If the dot lies below the blue line, the rating has worsened since 2013. Blue dots show an improvement, orange dots a moderate decline, and red dots a large decline (20 per cent or more than the average decline).

Three factors other than the budget cuts appear to have been particularly important in explaining the perception of reduced effectiveness. These are the attributes that declined the most and which were clearly associated with individuals’ responses to the question about changes in overall aid effectiveness.

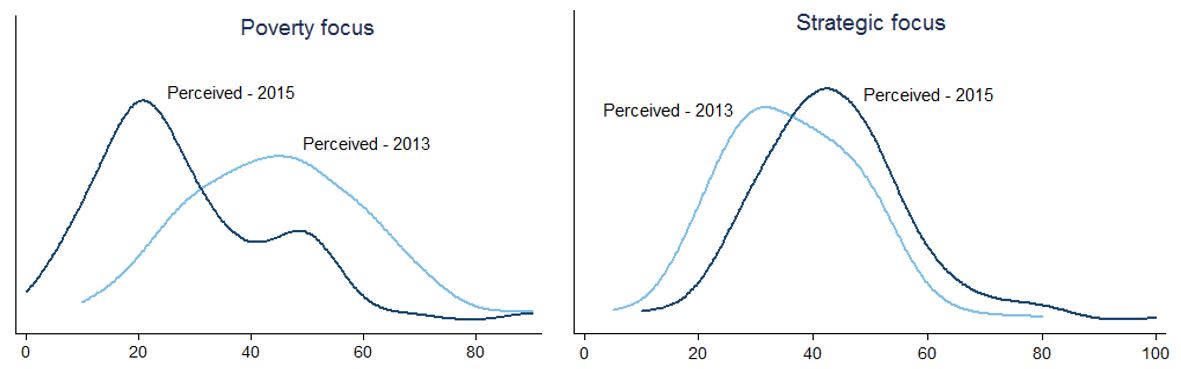

First, stakeholders perceive a loss of strategic clarity. They also express concern that helping poor people in developing countries has become a less important goal for Australian aid. Australia’s strategic and commercial interests are now seen to play a larger role in shaping the aid program. Relatedly, respondents are unhappy with the aid objective introduced by the Coalition in 2014, and the aid program is seen to have less realistic expectations than it used to.

Figure notes: These graphs show the distribution of responses in 2013 and 2015 to a question that asked respondents to allocate relative weights (out of 100) for various aid goals: poverty reduction, strategic interests, and commercial interests.

All this suggests that attempts to reposition the aid program under a “new paradigm” and as a form of “economic diplomacy” have not yet gained traction. The government has been making the case that aid is good for Australia. It needs to do more to communicate the message that the aid program is good for the world’s poor. And expectations need to be realistic, especially in a constrained aid budget environment, and difficult environments like the Pacific.

Second, a loss in aid expertise is viewed by the sector as a clear cost of the AusAID-DFAT merger. Nearly three quarters of 2015 respondents view staff expertise as a weakness or a great weakness of the aid program, up from half in 2013. More than three-quarters say that the merger has had a negative impact on aid staff effectiveness. A number suggest that the loss of staff expertise was not only a product of a large number of AusAID staff leaving after the merger, but also a consequence of an organisational culture within DFAT that fails to value development expertise. This is a problem that DFAT will have to address, or else it will grow over time as more former, senior AusAID staff and advisers leave, and as old projects end, requiring more new programming.

Third, transparency and community engagement have gone from being strengths of the aid program to weaknesses. The transparency score went down the most after funding predictability. In 2013 fewer than a quarter of respondents thought transparency was a weakness or a great weakness. In 2015 just over a quarter assess the aid program’s transparency positively. Respondents are clearly concerned about less information being available about the Australian aid program. DFAT has committed itself to aid transparency, and its coverage of aid on its website is improving, but clearly more is needed. Giving political backing to a detailed aid transparency commitment – in effect, a new transparency charter – and then reporting performance relative to this standard could quickly reverse the negative perceptions that have developed in this area.

Stakeholders also feel much less of an effort is being made to engage the community in relation to aid. This rating has gone from average to third lowest. This would be a natural area for the new Minister for International Development and the Pacific, Steven Ciobo, to lead on: communicating the successes and importance of the Australian aid program.

The aid budget cuts may not be reversed, but the decline in perceived effectiveness can be. Stakeholders are realistic about the prospects for future aid volumes, but they expect a more effective aid program. It is not as if our aid experts were fully satisfied with the state of Australian aid in 2013. Far from it. Now, though stakeholders still feel that they are delivering good aid, they give some clear indications that the quality of our aid is at risk. Listening to their voices will go a long way to minimising those risks, and putting Australian aid once again on an upward trajectory, if not in terms of volume, then at least, and just as importantly, in terms of quality.

Terence Wood is a Research Fellow, Camilla Burkot a Research Officer, and Stephen Howes the Director of the Development Policy Centre. The 2015 Australian aid stakeholder survey report, ‘Australian aid: signs of risk’, as well as a 4-page summary and all of the underlying survey data, are available for download here.

Leave a Comment