The 2016-17 budget was described last night by Ross Gittins, the economics editor for the Sydney Morning Herald, as a “plan to get Malcolm Turnbull re-elected”, “neither agile nor innovative”, but “a cautious budget, with little to which many people will take great exception”.

The description is apt when applied to the aid budget.

The government has done an excellent job of minimising the political damage associated with a (not unexpected) 6 percent cut to the aid budget (or 7.5 percent in real terms).

There is minimal change, in nominal terms, to the DFAT country program allocations. Strictly, that means that everyone is a loser, due to inflation. But that’s not something people tend to notice, and nor is the cut a big one.

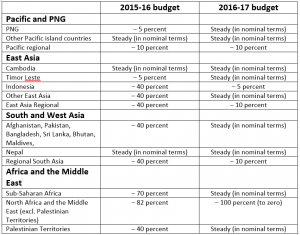

Indonesia is one exception – at least among country programs. It has had its aid budget cut by 5 percent (in nominal terms), although this is really only a product of an accounting exercise, which sees Indonesia’s debt-to-health-swap reclassified as a global program. The other country program to change is Fiji, which has seen its allocation increase from $35m to $51m as a result of Tropical Cyclone Winston. Cambodia’s allocation remains the same on paper, but this incorporates a $10 million increase included in the revised estimates published a few months ago.

Table: Summary of changes to country allocations, 2015-16 and 2016-17

So, where are the cuts? How has the government reduced the aid budget by 6 percent in nominal terms without cutting country allocations?

This is where Gittins’ description is less on the mark. The changes to the aid budget are clever, at least in an accounting sense. The big changes to the aid budget relate to cash payments to multilaterals, which have been timed in such a way as to reduce their impact on the 2016-17 budget (thereby keeping good on the cuts forecast by the government). Allocations to the UN, Commonwealth and Other International Organisations in 2016-17 decline from $334 to $199 million as a result. Payments to multilateral development banks similarly decline by $55 million.

Regional program allocations have also declined across the board. DFAT stressed in the lockup that this was simply “re-profiling”, and that in the forward estimates funding for regional programs remained unchanged. Of course, those forward estimates aren’t available, and they could change in the future, so it’s hard to verify whether these cuts are in fact simply another clever accounting exercise, or whether they’ll have a real impact on the aid program.

One very obvious feature of the country allocations is that they bear no relation to the performance of aid in those countries. How could they after all, unless all country programs have performed equally, with the exception of Fiji and Indonesia?

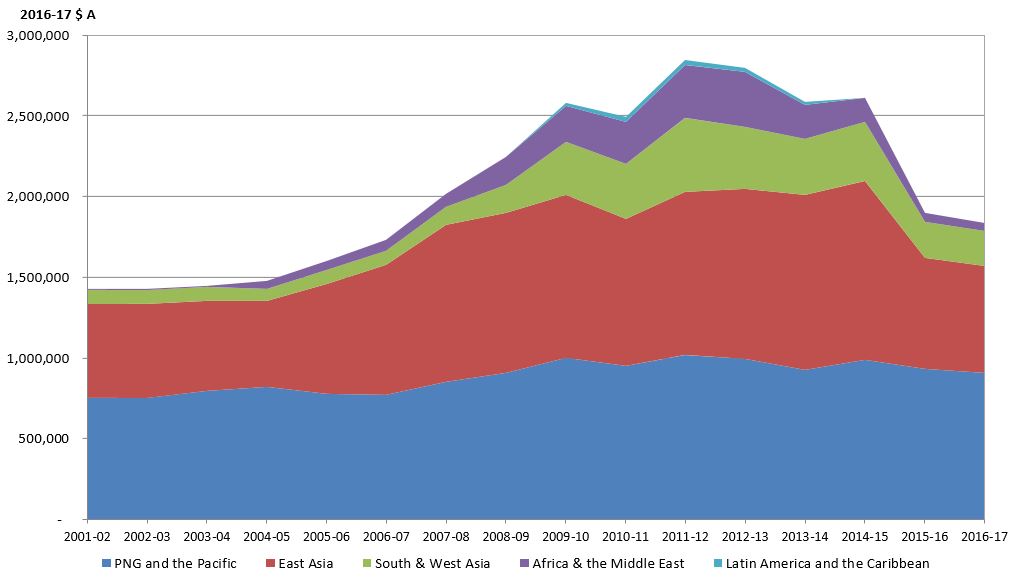

This was a point I made last year in relation to the ‘maintain aid to the Pacific, cut everything else’ strategy adopted in the 2015-16 aid budget. It was also something that Jacqui De Lacy pointed to in her presentation at last year’s aid budget breakfast. If we were to take the government’s performance framework at its word – that “the Australian aid program … links performance with funding” – we would see cuts to programs in PNG and the Pacific, which remains the worst performing region despite some improvement in the last year. But we don’t see that. For a number of good reasons, mind you (some of which were raised by Secretary Varghese in his speech at the aid conference) – but it’s an observation that looks odd in light of the aid program’s performance framework, and one that highlights the limits to concepts such as ‘value-for-money’.

Figure 1: DFAT country and regional allocations (constant prices)

A final point concerns innovation, and beyond that, change in the aid program. Innovation is a word that has been highlighted again and again in relation to the aid program. It’s something that the Foreign Minister has stressed. It forms part of the official aid policy. And Secretary Varghese mentioned it earlier this year in his speech on aid (“innovation needs to become core to our business”). That rhetoric is not strongly reflected in the budget figures, notwithstanding the increase in funding for the Innovation Fund, which rises from $20 to $50 million (still small change in an aid program worth $3,827.8 million). In the 2015-16 budget, the aid program reverted to the way it was before the scale-up, both in terms of overall aid volumes, and country/regional focus (see Figure 1). This year country allocations largely remain unchanged. ‘Continuity with change’ is the way Julia Louis-Dreyfus might describe the situation. Despite obvious changes, there remains a lot that is consistent about the aid program – from the focus on the ‘Indo-Pacific region’, to results (reflecting value for money), control of corruption, and even aid-for-trade (which involves the re-branding of many activities that have always been undertaken by the aid program, and importantly, has not led to the re-tying of aid). That continuity may not be innovative, and it is often downplayed or concealed by a government eager to differentiate itself from its predecessors. But it is positive, bearing in mind the disruptions caused by the integration of AusAID into DFAT, and the unprecedented cuts to the aid program.

Matthew Dornan is Deputy Director of the Development Policy Centre.

Leave a Comment