What has the G20 done for low-income countries lately? Qua collective, awkwardly little.

From a global development perspective, the G20’s Brisbane summit was notable for two main things. First, it drew praise for adding some momentum to the multilateral climate change negotiations, thanks in large part to announcements by the United States and China, even if this outcome was unexpected and unwanted by the summit’s host government. Second, although the summit’s various outputs are replete with ritual references to “inclusive growth”, it disappointed civil society groups by trumpeting growth targeting while eschewing equity targeting.

The first of the above outcomes might prove positive for low-income countries, if momentum does in fact build over the year leading to the watershed Paris climate conference in December 2015. (Post-summit developments are encouraging.) The second might prove negative, if one thinks that equity targeting inside the G20 would have influenced policy outside it—perhaps by giving a benediction to something like the inequality reduction goal proposed [pdf] by the UN’s Open Working Group on Sustainable Development Goals. But what outcomes were delivered for low-income countries in the areas in which outcomes had actually been promised?

The G20 has been running a ‘development agenda’ [pdf] for four years now, supported by a Development Working Group of senior officials. This agenda aims, as leaders said at their Pittsburgh summit, to ‘reduce the development gap’ between G20 members and low-income countries. Framed initially by the Seoul Development Consensus (2010) and subsequently by the Saint Petersburg Development Outlook [pdf] (2013), the agenda has changed shape over time. For example, social protection, a founding priority, was dropped in 2013. The development agenda currently involves various ‘actions’ in five topic areas: food security, financial inclusion (including migrants’ remittances), infrastructure, human resource development and domestic resource mobilisation.

Under Australia’s presidency, priority was accorded [pdf] to three of the five topics above, namely infrastructure, domestic resource mobilisation and financial inclusion. (In practice, the line was, ‘we have three priorities, and two other priorities’.) These three topics were preferred on the basis that the G20 wanted to be in a position to ‘integrate’ development considerations into its wider concerns. Those wider concerns include inadequate long-term financing for infrastructure and tax-base erosion but not in fact, for a majority of members, access to financial services for their own poorer citizens. The latter topic was simply difficult to downgrade in priority.

So, in Brisbane, what happened in these three ‘mainstream’ areas?

First, the world will now be equipped with an ‘infrastructure hub’, which reportedly will operate in Sydney for a fixed period of four years with US$10‑15 million in annual funding provided mostly by Australia. This mechanism essentially aims [pdf] to link investors with projects, including by centralising information on project pipelines. While not pitched as an international development facility, it looks likely to operate as one. The need for it appears to have been entirely undemonstrated, no matter that it was politely welcomed by the international financial institutions who are already quite busy in this field.

Second, the G20 made a general commitment [pdf] to help low-income countries participate in and benefit from its efforts to address tax-base erosion within the G20 area—while also noting advice from the OECD that one of the biggest revenue-killers for low-income countries, not actually prevalent within the G20, is the practice of granting tax holidays willy-nilly to foreign firms. The G20’s actions in support of this commitment tend to the dull, comprising studies, the preparation of policy ‘toolkits’ and the provision of technical assistance in tax administration.

And third, the G20 re-affirmed [pdf] its 2010 target of reducing the global average cost of sending remittances to five per cent, but with no deadline specified. The deadline had previously been 2014. This target is still a stretch: the global average was 10 per cent in 2009 and is now at about eight per cent, meaning that around US$35 billion will line the pockets of money-sending agents this year. But at the same time it’s less ambitious than the target now proposed by the UN’s Open Working Group: a reduction to three per cent across the board with a maximum of five per cent for individual remittance corridors.

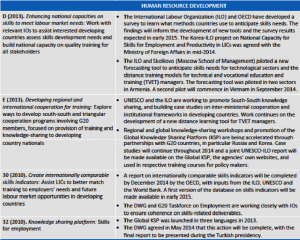

What of the two other priorities, namely food security and human resource development? The outcomes in connection with these ‘sidestream’ elements of the development agenda were particularly modest. The food security outcome was effectively that food security was not removed from G20 consideration. This followed an elaborate review [pdf] process and the development of a food security and nutrition ‘framework’ [pdf] that involves little more than keeping an eye on the previously-established Agricultural Market Information System (AMIS) and continuing annual meetings of G20 agricultural chief scientists. The outcomes on human resource development (under no circumstances should anybody read the verbiage reproduced above) were painfully process-oriented. It has never been clear what development business the G20 has in this area, and the results suggest none.

What of the two other priorities, namely food security and human resource development? The outcomes in connection with these ‘sidestream’ elements of the development agenda were particularly modest. The food security outcome was effectively that food security was not removed from G20 consideration. This followed an elaborate review [pdf] process and the development of a food security and nutrition ‘framework’ [pdf] that involves little more than keeping an eye on the previously-established Agricultural Market Information System (AMIS) and continuing annual meetings of G20 agricultural chief scientists. The outcomes on human resource development (under no circumstances should anybody read the verbiage reproduced above) were painfully process-oriented. It has never been clear what development business the G20 has in this area, and the results suggest none.

Nor was the G20’s pre-Brisbane form on development especially strong. The most concrete results for low-income countries had mainly been achieved in the area of food security. The G20 did set up AMIS. It had a go at piloting a regional emergency food reserve pilot in West Africa, though this fizzled. It lent general support to the AgResults initiative, a results-based financing pilot funded by a few of its members. It promised not to impose taxes or limitations on food aid exports. Beyond food security, it brought about the establishment of a ‘social protection inter-agency cooperation board’ for the multilateral system, span off the Global Partnership for Financial Inclusion and, as above, took over a remittance cost reduction target adopted by the G8 in 2009. In short, it provided a grab-bag of slightly random results which, in most cases, could and probably would have been achieved in a G20-less world.

Should we conclude that the creation of the G20’s development agenda was a misconceived and ultimately self-defeating bid for institutional legitimacy? There is some truth in that proposition, and the Lowy Institute’s Mike Callaghan has argued that it was a mistake to create a separate development work-stream. On this view, development in low-income countries, while an important concern for the G20, should have been, and should now be, mainstreamed in its agenda. Indeed, this was a view that the Australian presidency took on board in a half-hearted way with its ‘3+2’ approach to priority-setting.

To mainstream a development agenda in the G20’s work would be to confine it to G20-internal policy concerns, asking in each case, ‘By the way, what’s the development angle?’ That will in many cases be an important question to answer in the interests of both G20 and low-income countries. But the G20 should not confine itself to questions conforming to this narrow template. Part 2 of this post, next Monday, will argue that there was a case for creating, and that there is one for maintaining, a distinct development agenda for the G20—with certain characteristics and priorities.

Robin Davies is the Associate Director of the Development Policy Centre.