In November 2022 I wrote a blog predicting that Alatoi Ishmael Kalsakau’s reign was not guaranteed to last and that his government’s longevity would depend very much on how well he managed the interests of his eight coalition partners in government. This is a follow-up to that piece.

First, it is probably fair to say that Kalsakau’s government exceeded most people’s expectations. Not that he navigated all the pitfalls successfully, but he cleverly pulled at the people’s heartstrings with his pragmatic approach. Judging by the general atmosphere leading up to the Court of Appeal decision that effectively deposed his government, even today some feel he should be returned to power.

On the surface he appears to have done well by striking a chord with the people. I recount below why this might be so.

Immediately after assuming power in early November 2022, Kalsakau and Sato Kilman (who has now taken over as Vanuatu’s prime minister) took on the task of tackling one of the most important issues that had clearly undermined the national budget – a decision by the European Union (EU) to put a partial ban on Vanuatu citizens from entering Europe visa-free.

Since 2015, the EU had been concerned about the robustness of Vanuatu’s Citizenship by Investment Program (CIP), which it believed presented a significant security risk for EU member states. In February, Kalsakau himself travelled to Europe where he managed to obtain the EU’s agreement for Vanuatu to be granted an extra 18 months to properly address EU concerns over the visa waver agreement. To the ordinary eye, this was the work of a true leader.

In addition, whereas in the previous government that involved Kalsakau there had been serious allegations of maladministration and corruption, this Kalsakau regime provided a certain level of respite and confidence – thanks to the close watch of his coalition partners. There was also a noticeable improvement in the performance of ministers and their cronies.

Then in July, Vanuatu hosted one of the most successful and colourful Melanesian arts and culture festivals (MACFEST), the 7th such event to be organised in the region. MACFEST culminated in the celebration of the country’s 43rd anniversary of independence. Amidst all the fanfare, Kalsakau received one of the highest dignitaries from the wealthy G7 group, French President Emmanuel Macron. The last visit by a French president was General Charles de Gaulle 67 years ago.

While Macron had geopolitical ambitions spurred by a growing Chinese presence, Kalsakau grabbed the opportunity to raise formally for the first time one of the most delicate issues – the unresolved territorial boundary dispute between Vanuatu and France over two rocky outcrops in the southern part of the archipelago. It was later reported Kalsakau received immediate assurances that the question of Matthew and Hunter Islands would be resolved before the end of the year.

These milestone breakthroughs enhanced Kalsakau’s public image and his popularity, winning him praise from a broad cross section of people, not least from his own Union of Moderate Parties (UMP) diehards.

Meanwhile in June, a populist policy to raise minimum wages from 220 to 300 vatu per hour came into force. This was part of an election promise that had not been fulfilled in the previous government where Kalsakau was deputy prime minister. But the increase was received with mixed feelings, with the business community up in arms against the rise. They felt Kalsakau’s government could have sat down with them and heard them out first so that a more balanced approach could have been taken.

The then opposition felt the increase was not justified, although at times it felt they were simply toeing the private sector line, without saying anything new. At that stage both sides of the argument were genuinely true, in that while the government needed to help workers with rising costs of living, the private sector was the only golden goose, so to speak, given the EU ban on citizenship sales.

Positivity aside, deep within the UMP party ranks there was disaffection and dissatisfaction right from the start. Some time after the formation of government, two of Kalsakau’s own UMP party MPs gradually distanced themselves by hanging out more with the opposition. Port Vila’s rookie UMP politician Anthony Harry – now the new Minister for Internal Affairs – and member for Efate Rural Samuel Kalpoilep – appointed new Agriculture Minister – fell out of favour with their own government over internal party disputes. Surprisingly no one, not even Kalsakau, did anything to try and bring them back into the fold. Perhaps he should have read the early warning signs.

To rub salt into the injury, in May (barely six months in) when then Deputy PM and Lands Minister Sato Kilman was sacked over reports he was flirting with the opposition, Kalsakau pulled no punches and brought in Vanua’aku Pati (VP) member for Shepherds Outer Islands John William Timakata, himself a lawyer by profession, to fill the Lands portfolio. This angered VP, but also raised a few eyebrows from within UMP ranks – further exposing the cracks.

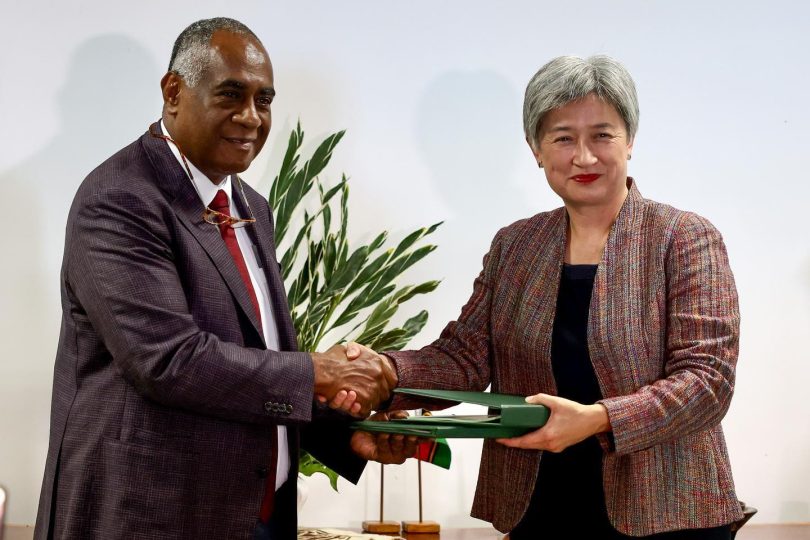

But one of the main reasons for Kalsakau’s downfall could be this. Very early in his reign, Australia sent its foreign minister Penny Wong on a Pacific tour in an effort to boost its Pacific ties, amidst a growing geopolitical rivalry for influence in the Pacific. The tour resulted in the signing of a security pact that did not go down well with either the opposition or the government.

For the opposition, such a security pact with Australia undermined the country’s long-standing position in the region of non-alignment, with all partners including China always accorded the same treatment.

To put it mildly, some felt Kalsakau lacked consensus building skills. For him to unilaterally decide on something so significant to Vanuatu’s foreign policy and long-term economic interests, without consultation with coalition partners, was unacceptable. This is something the incoming government has already indicated they will revisit.

It is not easy to predict what will happen next but with Kilman’s government having even more fragmented groupings, there are still no guarantees for success. Vanuatu might even return for an early poll if instabilities continue and the president dissolves parliament once again.

Well synthesized

A good piece, tankyu tumas Kiery for this analysis.