Last Thursday, September 19th, we released preliminary results from the 2012 PEPE (Promoting Effective Public Expenditure) survey of schools and health clinics undertaken by the National Research Institute (NRI) and the Australian National University’s Development Policy Centre. The survey included randomly selected schools and health clinics (but not hospitals) from eight provinces in a nationally representative sample. The provinces covered were Gulf, West Sepik, Morobe, Enga, Eastern Highlands, National Capital District and East and West New Britain.

Our 2012 survey included the same 166 schools and 63 clinics surveyed ten years ago by the NRI, in 2002. (In total we visited 214 schools and 141 health facilities.) By comparing the results from 2012 with those from 2002, we are able to address, for the first time, the pressing question of whether PNG has so far been able to translate its booming mineral wealth into services for ordinary people.

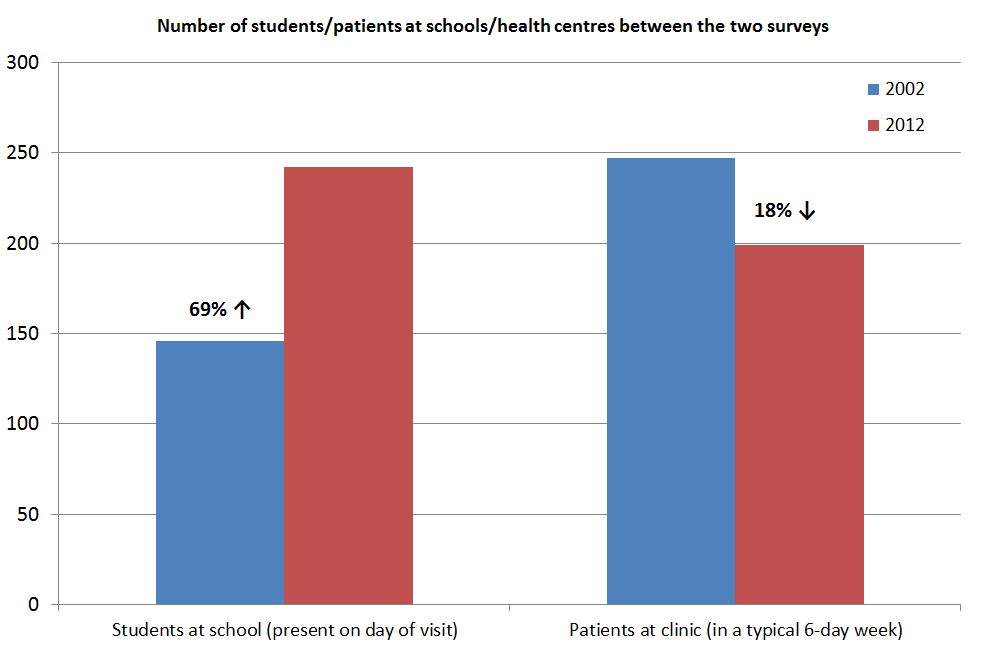

The results are revealing. The most striking difference is that the number of children recorded as being present at school increased by 69%, whereas the average number of patients utilizing a health clinic fell by 18%. We also know that the population grew over the last decade by about 30%, and that the number of schools increased slightly, whereas the number of health clinics fell. Putting all this together, we can conclude that the proportion of kids attending primary school increased by more than 40%, whereas the proportion of the population utilizing a health clinic fell by more than 50%.

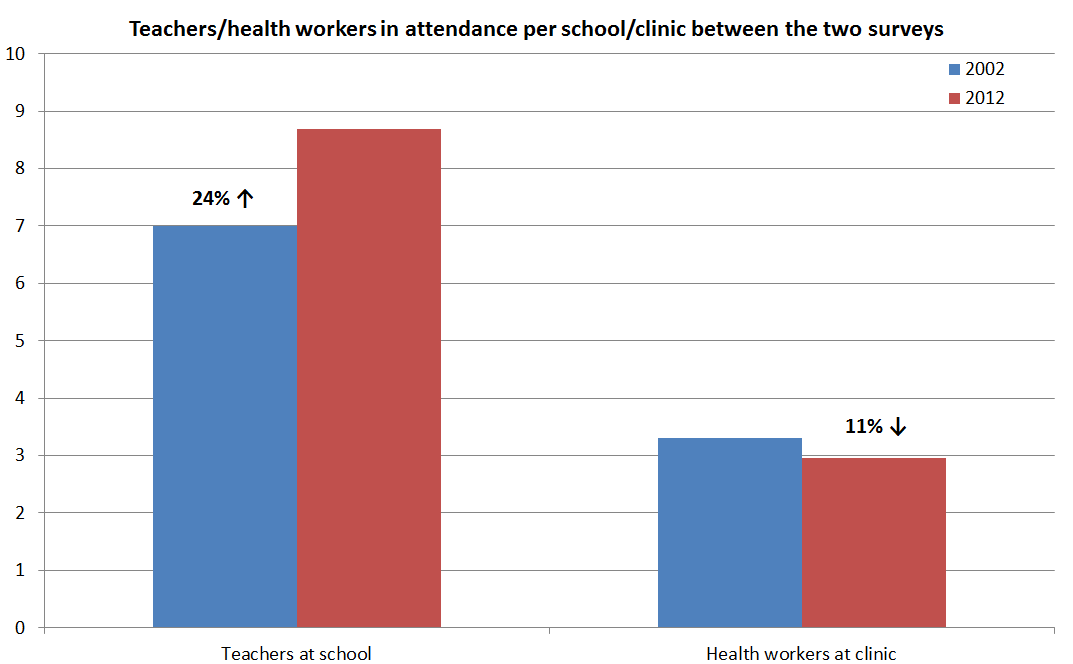

There are other indicators that the education sector has done much better than health. The number of teachers and classrooms increased over the last decade, the quality of classrooms also improved, and teachers reported greater adequacy of school supplies, such as textbooks.

There are other indicators that the education sector has done much better than health. The number of teachers and classrooms increased over the last decade, the quality of classrooms also improved, and teachers reported greater adequacy of school supplies, such as textbooks.

The performance of health clinics unfortunately went in the opposite direction over the last decade. There was a decline in the availability of some key drugs and medical supplies. While many health staff are clearly very dedicated (three-quarters contribute from their own salary to running costs), the number of health staff working at clinics fell by around 10%, as the graph below shows.

This is not to say that there are not problems in education. To the contrary, the results show schools face some of the same problems which hinder health clinics. For example, about 40% of staff homes for both teachers and health workers and 25% of class rooms and clinics require rebuilding due to a lack of maintenance.

Nevertheless, these clear differences in the direction of performance between the education and health sector over the last decade demand an explanation.

The policy of abolishing school fees has boosted school attendance, but the number of clinics charging fees has also fallen. The new policy of free health care will not be enough to turn around performance, and indeed may exacerbate existing problems as health centres are starved of cash.

The analysis undertaken so far suggests four reasons for these differences. First, more teachers have been hired than health workers. The inability to replenish the health labour force is a critical problem which will require both funding and training to address.

Second, primary schools have benefited from funding direct to schools from the national government (85% reported receiving both their 2012 subsidies). By contrast, health centres are reliant on the health function grants, and in most provinces these funds are not reaching the health centres (whether directly or in-kind). As a result, they are unable to carry out basic functions such as patrols and drug collection or distribution.

Third, primary schools seem to be better connected to their communities. Nearly all have boards of management with community representation and a parent and citizens (P&C) committee. Health clinics don’t have a board of management and only 60% have a village health committee. School P&C committees are also more active than village health committees, meeting almost twice as often on average.

Fourth and finally, primary schools are more likely to receive a visit from their supervisor than rural health clinics are.

These initial results illustrate the sort of analysis now possible with this unique longitudinal data set. Other results presented and discussed last week show that there is enormous variation in performance across provinces. A lot can be learnt from looking at the better-performing provinces. There is also some evidence that church-run health facilities perform better than government ones. We will be releasing further results and analysis in the coming months. We will be also undertaking much more detailed analysis at the facility level to better understand the determinants of performance over the last decade. We look forward to sharing more detailed findings from the survey as they become available.

The fact that we can now look at these questions shows just what a huge gap this new data set fills in our knowledge about service delivery in PNG. For the first time we actually have data on what is working and what is not, what has improved and what has gone backwards in service delivery in PNG.

While data and analysis are essential, so too are engagement and dialogue. The point of this exercise is not to lay blame or to point fingers. Over the last month, we have gone back to seven of the eight provinces from which we collected our data last year, presented our preliminary results, and sought their feedback. All have welcomed the availability of this new data and expressed their desire to use it to improve service delivery.

And last week we had the Acting Secretaries of both the Education and Health Departments there for the entire forum. Both talked about the value of this data, and the way they want to respond to its findings.

Was the last decade a lost one for PNG? As often happens, the answer is more complex than the question suggests. The last ten years have not been good ones for the health sector, and it is hard to see evidence of the additional money allocated to the sector on the ground. But for education, while many challenges remain, there are also important indicators of significant progress.

This variable performance has much to teach us. Free education or free health is not enough to guarantee expanded and improved provision of service. Getting frontline staff in place, getting funds and/or resources to the facility level, and strengthening community engagement and supervisory arrangements all seem to be important for improving service delivery in PNG.

Thomas Webster is Director of the PNG National Research Institute, and Andrew Anton Mako is a Research Fellow and PEPE Manager at the NRI. Stephen Howes is Director of the Development Policy Centre at the Australian National University. Anthony Swan and Grant Walton are Research Fellows at the Centre, and Colin Wiltshire is the PEPE Manager at the Centre.

Presentations made at the September 2013 PNG Budget Forum are available here. More information about the PNG PEPE project is available here.

Hi Grant & Jane,

Firstly, thank you so much for the very informative comments. I accessed this link by chance and by reading your commentary, it has opened my eyes and mind to two of the biggest social indicators that require a lot of budget funding and application in the right areas (priorities). I come from the Gulf Province and would love to see your full report – PNG’s lost decade? Understanding the differences between health and education for the Gulf Province, including the other 7 provinces. I have been a teach for 6 years, and my spouse is now in her 28th years of secondary school teaching hence, the data you have compiled in your research will be very useful to me as a citizen of this beautiful country and from Gulf. My contact details are stated below: Looking forward to your response. Thank you

Hi Thomas – I will leave it to Grant to respond as he has the data. Congratulations on your many years of service to PNG. It is the dedication of you and your wife and the many like you that give cause for optimism about the future.

Thanks Thomas.

Great to hear from you.

The Lost Decade report can be downloaded here. Email me if you have trouble downloading it – grant.walton@anu.edu.au. We’ve been conducting follow up research into the performance of schools and health facilities in both Gulf (Kikori and Kerema) and East New Britain. We visited both these provinces earlier this year. I’ll send you a recent presentation on our preliminary findings. We’ll also be presenting on our recent findings at the upcoming PNG update in Port Moresby on 4 November at UPNG.

Wishing you and your wife all the best.

Thanks for the reference Jane, we’ll be sure to check it out.

Hi Grant,

An understanding of history teaches us about the present – the table below is in the reference I cited – it helps understand the precedents of the “lost decade.”

Table 1: Key contextual factors which have shaped the health system

Pre-Independence (Pre 1975)

• Significant gains made in the health status of the population, with improvements directly attributed to the provision of health services (2).

• Centralised organisation and administration of health services, with highly-defined vertical public health programmes designed and implemented with emphasis at the district level.

• Highly centralised control ensured effective management of resources by a functioning bureaucracy that closely supported delivery and management of health services.

• Provincial hospitals provided technical and logistical support whenever required.

• Significant numbers of international contract officers in line management and service roles at national, provincial and district levels.

Early 1980s

• Australia provided direct budget support after Independence.

• No bilateral donors in the health sector (only the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and the World Health Organisation (WHO); and ADB funds flowed through the government budget).

• Coordinated process in place for planning the development budget, and clear separation of the recurrent and development budgets.

• Organic Law on Provincial Government (OLPG) – Rural health services were transferred to provinces; hospital services were delegated to provinces. (See also Day in this volume).

• National Department of Health (NDoH) left with no effective mechanism to maintain standards and ensure health policy implementation in hospitals and rural health services.

• Provincial governments saw the decentralisation as a chance to ignore the NDoH.

• Appointment of provincial health officers became politicised.

• Mobility of the health workforce declined as staff became part of provincial establishments.

• Functional roles and responsibilities were poorly defined; leading poor resource allocation, lack of coordination and inefficient management of health services, and the deterioration in quantity, quality and coverage of basic health services.

• Wingti Government redirected resources to economic sectors, resulting in a progressive decline in the available resources for the operation of health services.

Late 1980s

• 1986 – Australia began discussions about moving from budget support to programmed aid.

• PNG reacted by turning to other donors. In a very short period, the following donors became active in the health sector: United States Agency for International Development (USAID; Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA); People Republic of China and the European Union (EU). The net effect of multiple bilateral donors created a huge management burden on the NDoH. Much of the funds were extra budgetary funds and not reflected in official budgets.

• 1983–1988: real per capita expenditure for health fell by 9%.

• Capital expenditure on hospitals fell from about 14% in 1978 to 4.5 % in 1987.

• Projected a shortfall of K24.7 million in 1995 to grow to K40 million by the year 2000 (19).

• Aid post orderlies became public servants.

• Rural patrol allowances were more than doubled in a single decision, but were not budgeted for, with the effect that patrols were significantly reduced.

1990s

• Major revenue shocks.

• Bougainville crisis – Bougainville contributed approximately 16% of national revenue.

• 1990 – 10% devaluation of kina.

• 1994- further devaluation of 12 % and floating of kina resulting in further devaluation.

• Progressive reduction in Australian budget support from 24% of total revenue in 1984.

• Staffing shortfall estimated to be 1,440 nurses and 1,655 community health workers (3).

• Public Hospitals Act (1994) makes hospitals quasi-statutory authorities, responsible to an independent board of management reporting to the national Minister for Health—largely causing hospitals to stop supporting the rural health care system.

• Economic crisis point in 1994–1995, with several branches of government unable to meet debts or salary commitments.

• Structural adjustment programme and a programme of microeconomic reforms including to reduce public servants— aid post orderlies, now public servants were shed in large numbers by provinces as part of the reforms.

• By 1999, the Australian Agency for International Development (AusAID) had 16 separate projects and programmes operating in the health sector.

• In 1999 the Secretary for Health reported he spent 70% of his time servicing donors.

• In 1999, the NDoH requested that AusAID support a move towards a Sector Wide Approach (SWAp) in the health sector.

It is disappointing to see that in the presentation of the results from the survey on the changes in Education over the past decade in PNG that there was no measurement of the learning outcomes from the increased expenditure. There are many other measures of outputs shown, such as enrolments, student attendance, and teacher behaviour. But there is no measurement of the most important outcome–whether students improved in the Three Rs. In his latest book, “Schoolin Ain’t Learnin”, Lant Pritchett reports that enrolments, attendance, and such have been increasing across the developing world. But reading levels have not improved at all!!

I would have thought that the main lesson from studies on the effectiveness of aid–that we have to measure outcomes–would have been learnt by now.

Hi Ron,

Thanks for the comments. The blog highlights some of the preliminary results from the PEPE survey. We’re still in the early stages of data analysis, which has been focused on outputs (we’ve got at least another year of analysis still to come). Over the next few months we’ll be examining how the schools we visited faired in terms of student performance, and we’ll look at some of the drivers of education outcomes.

Having said this, the preliminary results do augment our understanding about the condition of schools and health facilities, and how this has changed over the past decade. Policy makers are finding these results useful. Our findings have informed debate around the new free health policy, and the Acting Education Secretary has said he’ll use the results to argue for a prioritisation of education funding. You can hear the Acting Education Secretary talk about the findings of the PEPE study here: http://www.radioaustralia.net.au/international/radio/program/pacific-beat/png-government-tackling-shortage-of-thousands-of-teachers/1203380

Cheers,

Grant

The findings of this report are sadly unsurprising.

In the Papua New Guinea Medical Journal Volume 52, Number 3-4, September-December 2009, Focus Issue on Health Systems Strengthening, edited by Professor Maxine Whittaker and me – we review the achievements and lessons from the past decade and provide some leads on where, investments should be made to improve the outcomes of the health system. We emphasise the need to focus on five basic elements:

1. Effective interventions for main causes of morbidity and mortality; where and when required (these are well articulated in the national health plan)

2. Skilled health workers at the point of service who are able to provide those interventions (this is an issue that was identied in the 1980’s and has received insufficient attention)

3. Essential logistical elements to enable the health worker to provide the effective intervention (drugs, medical supplies, equipment, transport, treatment guidelines etc)

4. Information, education and communications, and other health promotion initiatives andefforts directed at communities—to obtain their cooperation and acceptance of the interventions; and to support and empower their engagement in healthy behaviours

5. Population coverage.

These remain the priority needs of the PNG health system.