There’s a worrying cavity at the core of Australia’s aid program. Certain uses of aid are more ‘core’ than others, in that they generate benefits far beyond specific social groups or sectors of the economy. Few uses of aid are so core as investments in water and sanitation. Yet there is too little recognition of this in Australia’s current aid policy and allocations.

Water and sanitation programs have borne more than their share of the pain inflicted on the Australian aid program as a result of the major cuts implemented since 2013-14 (Figure 1). The average level of spending in 2014 and 2015 was about 50% lower than it had been over the previous four years. The share of aid devoted to water and sanitation is now much smaller than it was four or five years ago.[1]

Fig. 1: Bilateral aid for water and sanitation, Australia, 2002-15

Source: OECD aid statistics

While a sharp reduction in Australia’s aid budget was bound to reduce the absolute level of investment in water and sanitation programs, it need not have reduced the relative level as it did. Given the effect of the spike in expenditure in 2010 and 2011, perhaps it is too early to extrapolate from the downward trend in absolute and relative investment levels since 2013. However, this is something that bears watching.

Regardless of what might happen in the future, we take the view that steps toward a restoration of something like the average funding levels seen in the 2010-13 period would be justified. There are at least two important reasons to give water and sanitation a higher priority than it is now receiving, not only in budgetary but also in policy terms.

Water for women and girls

The first reason is that, in addition to its fundamental importance to agriculture and every aspect of a country’s economy, water is at the heart of one of the government’s declared priorities: gender equality and women’s empowerment.

Long ago, in 1992, the Dublin Statement on Water and Sustainable Development recognised the interdependence between, on the one hand, women’s wellbeing and empowerment, and, on the other hand, access to water, sanitation and hygiene infrastructure and services.[2] This has been reaffirmed in Sustainable Development Goal 6.

We’ve both had various opportunities to experience the benefits of water and sanitation assistance at first hand in neighbouring countries. For example, here’s Bob on a 2008 visit to Kiribati in his capacity as Parliamentary Secretary for International Development:

Probably because I was always heard ‘rabbiting on’ about water and sanitation I was invited to open a toilet block at a local school! I was pleased to do it, but found that it was even more important than I had thought.

School attendance amongst girls was lower than it should have been because of the lack of secure toilet facilities. Parents were genuinely in fear of girls being attacked as they visited the pre-existing toilets.

With the provision of the new, safer toilets there was confidence that the attendance of girls would be restored to its desired level.

Whether the issue is school attendance, safety while travelling distances to fetch water or maternal health, adequate, clean and accessible water is critical. For that reason alone, it deserves higher priority in the Australian aid budget and in Australia’s aid policy framework.

There is no doubt about the commitment of the Minister for Foreign Affairs to improving the circumstances of women and girls in developing countries. But without adequate funding for safe, secure and accessible water and sanitation the commitment will not translate as fully as it might into opportunities for the women and girls she is concerned about.

Water scarcity and conflict

A second important reason for giving greater policy and budgetary priority to water and sanitation, aside from its direct benefits for economic and social development in general, and its specific benefits for women and girls, is that investments in this area have the potential to avert or mitigate conflicts associated with water scarcity.

In the World Economic Forum’s 2016 Global Risks report, as in previous such reports, water scarcity was ranked as one of the world’s highest risks in terms of both impact and likelihood. The same report highlighted the strong link between water scarcity, climate change, food insecurity and extreme social instability. It also identified Asia as one of the two prime risk areas for water scarcity.

The other at-risk region, unsurprisingly, was Africa and the Middle East—and we have already seen five years of drought contribute to the commencement of the Syrian uprising which is still playing out. Somalia is an extreme case in terms of the length and intensity of its civil war and drought, but many of the countries of the Sahel have also experienced increasing civil conflicts in parallel with droughts.

Even where drought is not an issue, cross-border conflicts over the use of river water have the potential to arise in connection with the Mekong river, the Nile and other rivers of the Indian sub-continent and the Middle East.

Australia, it is reasonable to assert, has much to offer in terms of expertise in urban and rural water management and efficient water supply. There is an argument, in fact, for developing specific institutional arrangements to make that expertise available to developing countries, as we do in the area of agricultural research through the Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR).

More investment, on a stronger policy foundation

We have to wonder whether the recent falling away of investment in water and sanitation might be symptomatic of a strategic failure—a failure to appreciate the core developmental role played by such investment.

That speculation is certainly encouraged by an examination of the government’s current aid policy framework. The general significance of water and sanitation for economic and social development is registered there. Its fundamental importance for gender equality and conflict prevention is not. The government’s health for development strategy touches only lightly on the gender equality aspect.

We do not suggest that the government has obliterated funding for water and sanitation. Despite recent falls in spending, Australia’s multi-year portfolio of active water and sanitation projects is still worth some $800 million in total, with indicative forward commitments of $157 million.[3]

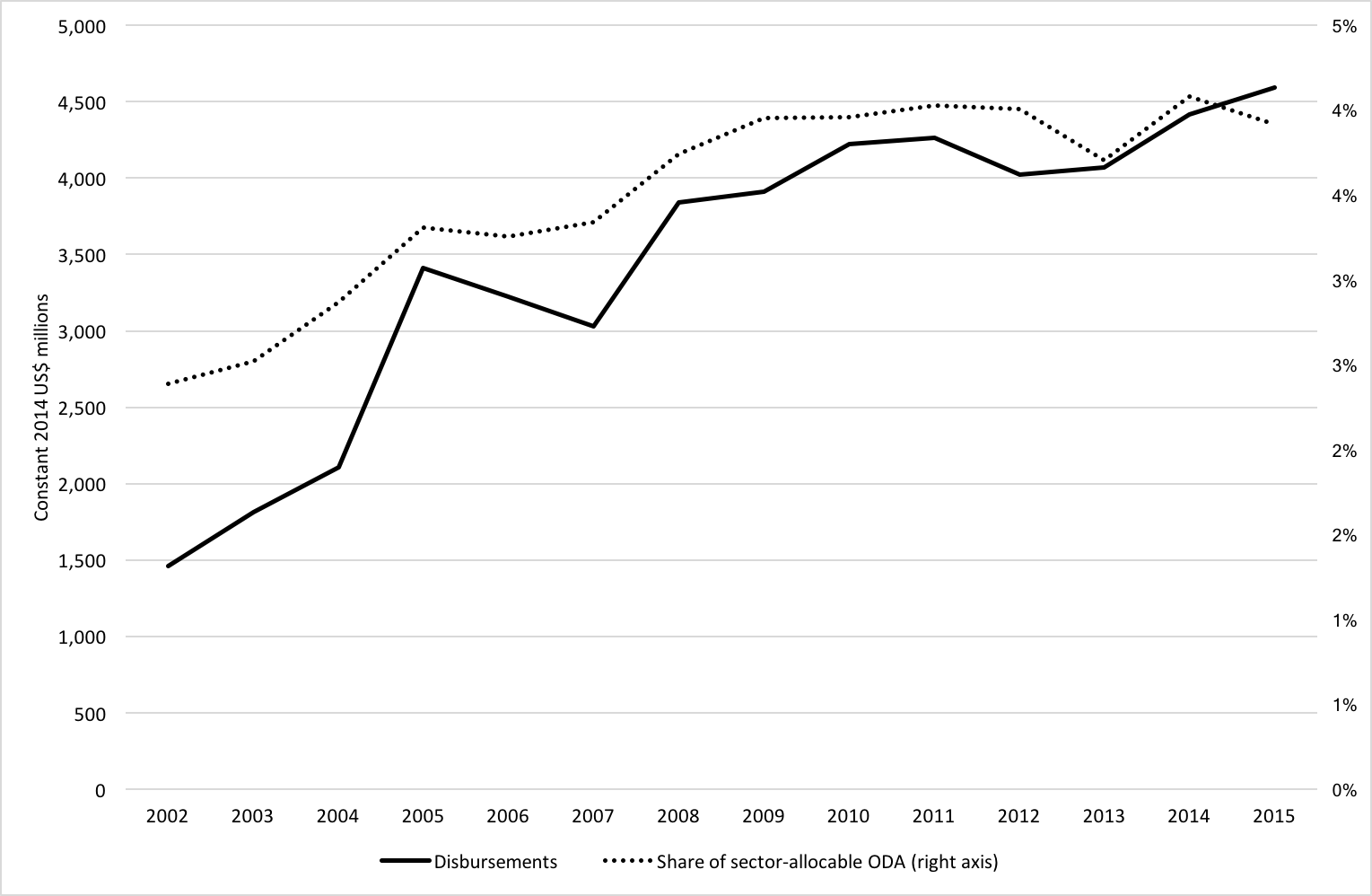

And, as at the end of 2015, Australia had not yet fallen very far below its OECD counterparts in terms of the percentage of bilateral aid allocated to water and sanitation—3.4% for Australia as compared with 3.9% for all OECD donors (Figure 2).

Fig. 2: Bilateral aid for water and sanitation, all OECD donors, 2002-15

Source: OECD aid statistics

Nor do we suggest that the government has been completely blind to the specific importance of water and sanitation for women and girls, or to opportunities to capitalise on Australia’s special expertise in this area.

For example, the government has decided that the existing Civil Society Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Fund will be succeeded by a $100 million, five-year ‘Water for Women’ initiative to be designed this year. And it has established an Australian Water Partnership—whose offices, as it happens, are a stone’s throw away from ACIAR.

However, there is no guarantee that that the $157 million that is yet to be spent on the existing portfolio will be spent in full, and the new water partnership is very modestly funded at $20 million over four years. While funding for the Water for Women initiative is more respectable, matching that allocated to the Civil Society Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Fund, it’s to be spread over five years and many countries.[4]

The present water and sanitation portfolio is not negligible. But nor is it as significant as it should be within the overall aid budget. The new measures described above might well be designed along the right lines but they are limited in scale.

What is really needed is a serious and long-term financial commitment to water and sanitation as a core, binding investment priority for Australian aid, grounded in a clear and central policy commitment. If nothing else, such a policy commitment should help drive any future restoration of Australia’s aid budget to more respectable levels.

Bob McMullan is a Visiting Fellow at the Development Policy Centre and was Parliamentary Secretary for International Development Assistance from 2007 to 2010. Robin Davies is the Associate Director of the Development Policy Centre.

[1] Expenditure on such programs, while guided by a dedicated policy document of the Howard government, had been running at a very low annual average of US$35 million, in constant 2014 prices, over the period 2002-09. This attracted some adverse comment at the time. Expenditure climbed steeply as a result of the Rudd government’s $300 million Water and Sanitation Initiative to US$175 million per annum over the four years 2010 to 2013. After the cuts, the average annual expenditure over the two years 2014 and 2015 fell to US$115 million.

[2] Closer to home, back in 2009, the evaluators of Australian-funded water and sanitation programs in Indonesia and East Timor observed in connection with both countries:

Women form the most active community group in the water and sanitation sector (because their roles include collecting water, using water to cook and instilling healthy and hygienic behaviours in children), yet women tend to have comparatively little influence on sector management.

[3] The largest ongoing commitments are in Indonesia ($200 million), Vietnam ($100 million) and Timor Leste ($60 million). The figures cited here are based on Australian government reporting to the data registry of the International Aid Transparency Initiative, which can be accessed via this ‘query builder’. This information, cleaned up a little, can be viewed in spreadsheet form here.

[4] In addition, it’s a cautionary fact that, halfway through the fifth year of a seven-year project, the Civil Society Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Fund has consumed only two-thirds of its budget.

For more information on gender and water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) and water resources management, please see the short summary report developed by the Institute for Sustainable Futures, University of Technology Sydney and WaterAid titled – Gender SDG6: The Critical Connection. This report was commissioned by the Australian Water Partnership/DFAT for the United Nations High Level Panel on Water, which Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull is a member of, and can be accessed at: https://waterpartnership.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/HLPW-Gender-SDG6.pdf