Do Australians support their government giving foreign aid? And if so, how much do they want given, and what do they want it given for? These seem like simple questions, but getting good answers to them is surprisingly complex. In the latest Devpolicy Discussion Paper we’ve drawn on findings from a range of opinion polls and surveys conducted between 2011 and 2015 in an attempt to answer them. The aggregate results offer both good news and bad, and plenty of scope for future investigation.

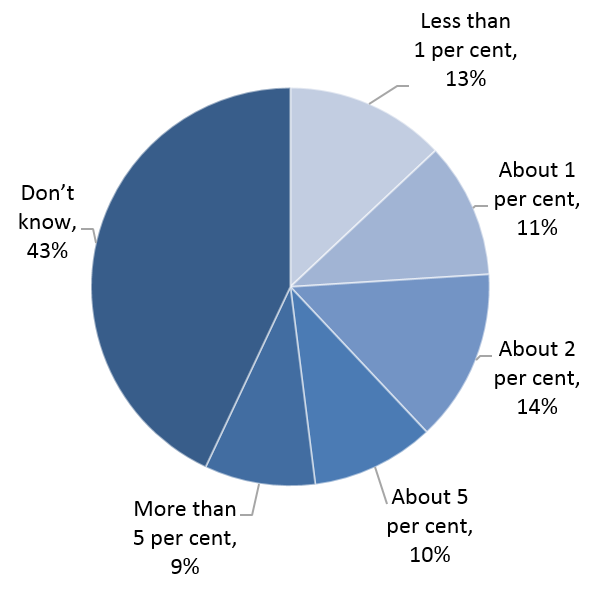

In good news, some of the survey data suggest that Australians are altruistic and generous when it comes to aid. When surveyed by an ANUpoll in 2014, 75 per cent of Australians approved or strongly approved of the government giving foreign aid to poorer countries around the world.

Support for foreign aid (May 2014)

Discussion Paper (DP) Figure 1. Source: ANUpoll, 12–25 May 2014

In addition, the majority of Australians believe that government aid should be given primarily on a humanitarian basis (in the sense of prioritising the needs and interests of the recipient country, as opposed to aid driven by domestic commercial and political interests). And most believe that it is important to give aid to countries in the Pacific and southeast Asia. As discussed in a previous post, this sense of regional responsibility largely aligns with how DFAT currently distributes the aid budget.

However, despite supporting foreign aid in principle, when it comes to the bottom line Australians’ enthusiasm tends to wane. For example, when asked in May 2014 about their support for a range of decisions made across the 2014/15 Federal Budget, 64 per cent of respondents expressed support for freezing foreign aid – the highest level of support for any decision listed, and 11 percentage points higher than the next most-supported decision.

Support for decisions in 2014/15 Federal Budget (May 2014)

DP Figure 5. Source: EMC, 20 May 2014

Note: results above omit responses in the categories ‘neither support nor oppose’ and ‘don’t know’

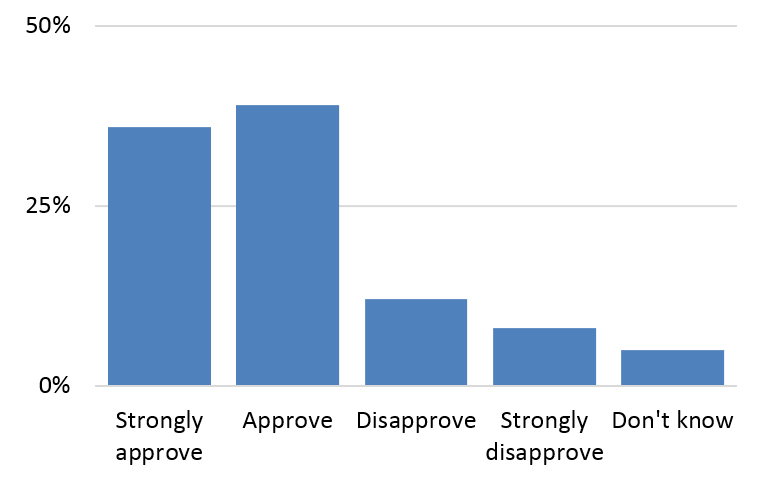

However, those sets of results that suggest most Australians want aid to be cut should come with an important caveat: only a small proportion of Australians actually know how much foreign aid Australia gives in the first place. Polls that asked respondents to identify the size of the aid budget consistently found that around 40 per cent of respondents simply ‘don’t know’. In the most recent of these polls, conducted in June 2015, only 13 per cent of respondents selected the correct answer (less than 1 per cent).

Knowledge of aid budget size (June 2015)

DP Figure 8. Source: EMC, 2 June 2015

Importantly, two polls from 2011 and 2015 reveal a general correlation between knowledge about the size of the aid budget, and opinions on whether it should be increased or reduced: both respondents who confessed to not knowing the size of the aid budget and those that thought the aid budget was larger than it actually was were, on average, more likely to respond that Australia spends ‘too much’ on aid.

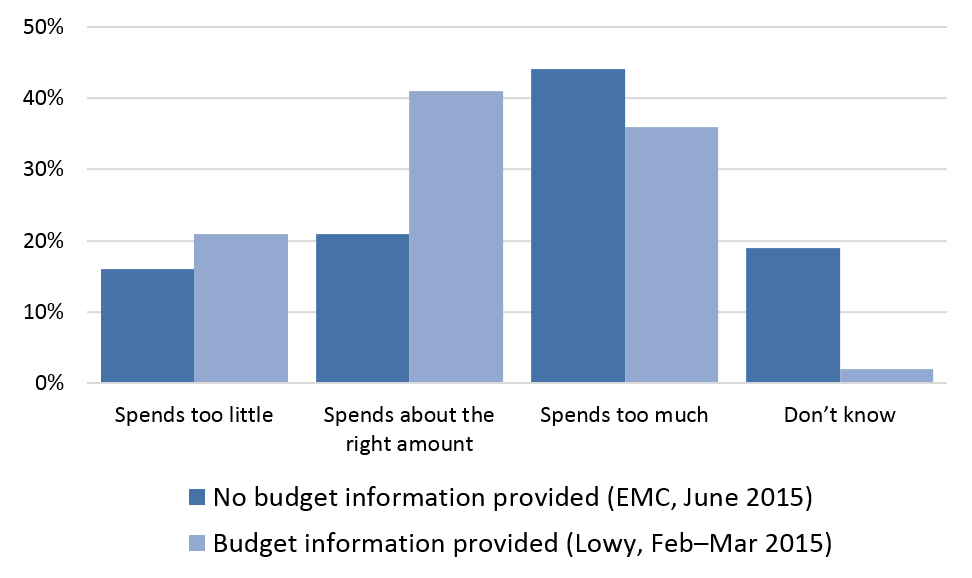

This finding raises the question of whether opinions of aid volume change in light of accurate information. Unfortunately, the jury is still out on this. The figure below compares the results from two poll questions on opinions of aid volume, one that did not provide any information about the size of the aid budget and one that provided specific information about the budget. Respondents to the former question are significantly more likely to believe that Australia spends the right amount on aid or that Australia spends too little, and less likely to believe that Australia spends too much.

Opinions on aid volume, when aid budget information is and is not provided

DP Figure 11. Sources: Lowy Poll, 20 Feb–8 Mar 2015 and EMC, 2 June 2015

However, other polls suggest that, when asked about aid in the context of government debt, Australians on average remain in favour of reducing the aid budget. This is particularly the case when they are asked about potential economic policy alternatives to cutting the aid budget – such as raising taxes, allowing the deficit to increase, or cutting other government expenditure, something that suggests that domestic concerns tend to trump positive feelings towards aid, even when people are better informed about the size of the aid budget.

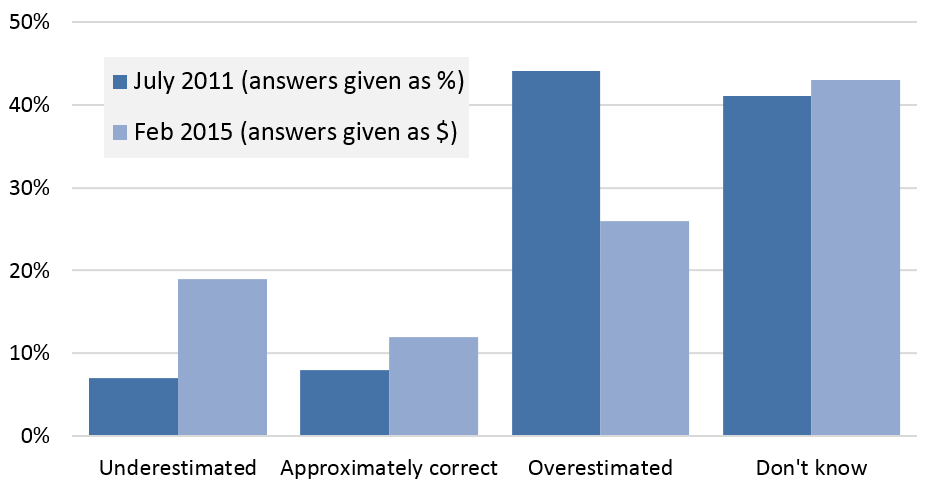

Although combining polls from different sources and time periods diminishes our ability to make concrete conclusions, the exercise of doing so also offers some insights into how question design may influence how people respond to questions about aid. For example, questions that ask respondents to estimate the size of the foreign aid budget yield different responses when they are phrased to seek responses about aid’s size as a percentage of the federal budget versus a simple dollar amount.

Estimates of foreign aid budget (2011 and 2015)

DP Figure 16. Sources: EMC, 11 Jul 2011 and Campaign for Australian Aid, 10-12 Feb 2015

These and other comparisons between polls suggest that the way questions are posed and framed may affect how people respond and may have a significant impact on reported levels of support for aid. At our end, as researchers, experimental work in this area is the next phase we plan to embark on in our program of research on public opinion on aid. Further analysis of the correlates of support for aid, following on from a previous Devpolicy Discussion Paper, is also underway. By developing a more nuanced understanding of what the public know about aid, what factors predict their support, and how survey design can influence professed support, we hope to be able to shed some much-needed light on the factors that shape public opinion and debate around foreign aid in Australia.

Camilla Burkot is a Research Officer at the Development Policy Centre. Terence Wood is a Research Fellow at the Development Policy Centre.

To anyone who has watched ‘Yes Minister’ and Yes, Prime Minister’ the subject of public surveys is very clearly explained when Sir Humphrey Appleby takes staffer Bernard aside and explains the process to him.

The results of any survey depend on what questions are asked and in what sequence.

Let’s go back to over half a century to the origins of the ‘Colombo Plan’ that began as a concept in 1949. What was the aim of the Colombo Plan? What obvious and lasting effects Australia’s continuous overseas aid program has really achieved? Was that due to the phenomenon of what’s known as ‘boomerang aid’ or was it due to the ephemeral effects of something similar to a short term ‘sugar high’? Was our aid to promote ourselves with our neighbours or to influence them politically? Was it to get a warm and fuzzy feeling that we as a so called lucky country could willingly share our good fortune?

If the answer is all these objectives and more then perhaps the real problem is that any process with a multitude of spoken or unspoken objectives often ends up being the proverbial ‘dog’s breakfast’ or a multi cobbled together animal built like ‘topsy’. If the huge amount of aid monies have achieved no long term advantage for Australia but in some cases only caused resentment then maybe we need to revise the concept completely? If our tax money goes to governments who then are able to use their own money to salt away funds in tax havens or even shall we guess, Australian banks, what practical benefits for the people at the grass roots are we really achieving? There’s no way we could or should get into a ‘bidding war’ with other and far larger economies. New Zealand seems to achieve far more with far less than Australia? Why is it someone at the decision making level isn’t logically starting to wonder?

The Australian economy is currently not the most robust with an exponentially growing deficit. Successive governments together with union pressure have allowed our manufacturing capacity to become unviable and shipped overseas due to unsustainable wage rises that keep trying to keep pace with inflation caused by previous wage rises. Can we therefore still keep funding overseas aid at the current level when ‘charity begins at home’?

Younger generations referred to as ‘X’ and ‘Y’ are reputedly now blaming us Baby Boomers for all the problems of the world and for impossibly expensive housing when they have enjoyed all the benefits we achieved with hard work and very little wealth and now seem unable to pass these onto the younger generation. Of course that is after the X’s and Y’s have demanded political change and more of everything without worrying about what that resulted in achieving. Responsibility? What’s that in political terms? ‘A week’s a long time in politics’ is a quotation attributed to Britain’s former PM Harold Wilson.

If there is someone who might possibly answer to the title of ‘the average Australian’ they aught surely to start questioning what we are actually doing in reality by allocating scare resources and funding to a ‘pie in the sky’ at a time we can least afford it. However the old obfuscation of ‘bread and circuses’ or today’s ‘football and welfare’ equivalent will surely be able to assuage any concerns within a few nanoseconds even if they appear at all in a proverbial and momentary ‘thought bubble’.

The real issue that is constantly obfuscated in the aid debate is hidden in the word ‘percentage’. Many claim Australia should give more when told what percentage of our budget is devoted to overseas aid. Yet how many actually take the time and effort to find out how much of our national cake is already spoken for with Health, Education, Social Security (pensions, etc.), taking up the vast majority of what is or might become available. Our Defence spending has woefully been allowed to subside in a time of increased world tension and where successive PM’s want to strut their stuff on the world stage with the US (here we are bro’) and try to get some glimmer of kudos to turn attention away from their dismal inability to manage our economy and provide true leadership.

The last factor that must be recognised is the inevitable legion of consultants, academics and so called ‘experts’ who glean a rich living from pontificating over whether we (i.e. ‘us’ others) should increase our foreign aid and by how much? How much of their salaries are the highly paid prepared to contribute to a non-focussed objective in a foreign and virtually ungoverned country where the money ends up be corruptly syphoned off into tax havens and personal bank accounts without ever achieving any real progress for those it was intended to help?

Have those that seek to influence our collective national aid program taken a constructive look and detailed investigation of what long term benefits of our long term aid programs have actually achieved? An example of what I’m referring to are the projects that purchase machines without any ongoing maintenance program. These are just like giving a useless plastic toy that gives a brief illusion of benefit but in fact only further increases the feeling of despondency of those who really are looking for help when it breaks and falls apart.

So what’s the answer? Start educating those who are giving the aid to understand what works and what doesn’t. Mere graphs and manipulated surveys that convey a false impression are only helping to perpetuate the problem. Start educating both those who contribute and those who are supposed to provide effective leadership about the realities of overseas aid. What’s that I hear you say? No votes or stipends in that…..

Thank heavens I haven’t become cynical in my senior years……..

Given the thunderous silence to my last observations on this subject I am persuaded by a recent article that has just appeared in the PNG media to add a few more suggestions.

It has just been announced by the Oz High Commission in PNG that 100 million Australian ‘aid’ dollars has been allocated to send Australian university students to spend short periods of time in PNG to ‘deepen their academic and life experiences through study and work placements in Papua New Guinea.’

These placements will be for periods of up to 4 weeks and apparently the students are to work alongside operational positions in PNG.

Who ever dreamed this idea up has surely got to be an under experienced denizen of an ivory tower in Canberra and no doubt in close contact with those who lurk behind the razor wire in the Oz HC.

What on earth can some young student gain by working for a short time (2 to 4 weeks) in PNG when they need to know and be well prepared to understand the customs, language and social conditions of the work area they are going to supposedly obtain some experience in. Apart from the distinct possibility that there may well be some very negative, short term culture clashes, exactly what will this ‘experience’ give Australia in terms of value for money or to PNG for that matter?

2 weeks to study ‘Leadership’ by walking the Kokoda track can no doubt give a great experience to whoever has been lucky enough to be given this opportunity and good luck to whoever it is. But on a broader scale, exactly what is Australia and PNG getting out of the $Aus100 million of taxpayer’s dollars that could not be better obtained by using these scarce funds to create a comprehensive training facility for both those who might be sent to PNG and those from PNG who are sent to Australia for training and experience?

If Australian taxpayers were actually told about the reality of how their taxes are being spent and these programs effectively audited on pre set and transparent benchmarks on long term, clearly definable benefits for both our nations, there might be some real value achieved.

Failing that obvious and non reported deficiency, I would be very interested to hear some concrete views on whether this exercise in spending 100 million dollars is of any long term benefit to either nation apart from perhaps creating some short term, personal e mail or facebook contacts that can’t possibly convey more than a brief impression of the disparate working conditions and a subsequent lack of any comprehension as to why this is so.

Hi Paul,

Thank you for your thoughts on this subject. On the whole, I don’t think we’re as much in disagreement as you seem to think we are. I’d like to respond to just a few points from your extensive commentary.

On your first, fundamental point, “The results of any survey depend on what questions are asked and in what sequence” – absolutely yes. Perhaps this is not adequately emphasized in the blog post, but this observation drives a large section of the Discussion Paper to which the post refers. As we note, this is also an area in which we hope to conduct more research, to understand better the ways in which surveys and polls may be used and manipulated by those on both sides of the aid debate.

Similarly, we also highlight in the paper (and in the blog) that, as you note, many Australians do not know how much of the national budget is spoken for by different areas, and how much funding might be saved. Yes, Australia is facing an increasingly negative economic outlook, and yes this means that there may not be as much funding to go around. But you seem to imply that there is waste and room to spare in the aid budget, and not in other sectoral areas; I would push back on that. For example, while there has recently been some media attention granted to fraud in the aid program, available data shows that the levels of fraud recorded by DFAT (and AusAID before it) have been significantly lower than fraud in a number of domestic programs and departments, including Defence.

On this basis too I would respond to your question, “Can we therefore still keep funding overseas aid at the current level when ‘charity begins at home’?” with an emphatic yes. It’s a false dichotomy to suggest that we can only do one or the other. But certainly we could, and should, seek to do both much better.

I also agree wholeheartedly that there is much to be gained by doing as much as possible to educate those involved with giving aid about what works and what doesn’t. You ask, ‘Have those that seek to influence our collective national aid program taken a constructive look and detailed investigation of what long term benefits of our long term aid programs have actually achieved?’ The answer is: not as much as we would like, but we are trying. Aid effectiveness has been a long-standing focus of this blog and of our Centre’s work more generally. But working to improve the evidence base and the effectiveness of the personnel and strategies within the Australian aid program does not necessitate ignoring public opinion altogether. I would suggest these can be parallel, not competing, activities.

For accuracy, I don’t think anyone is implying that we should “get into a ‘bidding war’ with other and far larger economies”. Of course it would be ludicrous to argue that, for example, ‘The US will give $33.7 billion in FY2016; why won’t Australia step up?!?” Generosity in giving ODA is typically measured as a percentage of GNI, precisely because it means we can make meaningful relative comparisons with other, much larger economies.

In sum: yes, public opinion is not the be all and end all. Yes, surveys can be misleading (and/or produce misleading results) and respondents may not be adequately informed to respond to them. These are all points we readily acknowledge in the paper, and aim to learn more about. And you certainly won’t find any objection from our corner that aid effectiveness could and should be improved. But I don’t think it’s particularly helpful — or accurate — to make blanket statements describing the aid program as a ‘multi cobbled together animal’, to insinuate that taxpayer dollars are more often than not ‘corruptly syphoned off into tax havens and personal bank accounts’, or to suggest that aid program personnel, consultants, academics, and other ‘so called experts’ are either oblivious to or don’t care about the problems and challenges inherent in giving aid, or are indifferent to the very real needs of aid’s intended recipients. No one is saying running an aid program is easy. It’s a messy, complex business. That’s precisely why we are interested in pursuing this research.

Camilla

Thanks Camilla for your detailed response. Yes, it is easy for someone on the outside to critcise however as you say, more should be being done. I guess it depends on one’s perspective and experience as to what one believes. I grant you that my perspective is far more focused on PNG than the rest of the world and in that aspect, I do have a modicum of experience.

The recent decision by Julie Bishop to cancel an obviously corrupt {NG Departmental decision over the aid funded PNG pharmaceutical contract is an excellent example of what needs to be done to stop ongoing corrupt use of our overseas aid money. This debacle was after two years of funding an excellent scheme that actually delivered the pharmaceuticals to where they were needed at K70 less than what the PNG government adopted outside of the official tender process. The pharmaceutical delivery process in PNG is now back to where it was prior to our aid funded program.

Naturally, nobody in Australia heard, knew or really cared about it because no one is educating the public in ‘how to connect the dots’. The public relies on the government to manage our economy (yeah right!) yet complains when they have to pay more tax or their savings disappear due to inflation or fund overseas aid.

I agree that we need to do more and especially more for PNG our closest neighbour. What is required is a national, overall managed approach to our overseas aid rather than the current scatter gun methodology. Individual programs need to be put to the acid test as to whether they are constructively helping those who need help or merely lining pockets on either side of the Torres Strait. Every project and program should first have set benchmarks that can transparently be seen as defining whether or not a program or project is helpful and sustainable and providing value for our aid money.

An clear example of the problem is the huge amount of funding devoted to sending Australian police to PNG, based on a previous PM to PM discussion. This has only resulted in those officers receiving huge financial incentives while PNG’s law and order problems just get worse and worse. At the end of the day, the PNG PM and the Police Commissioner have called the program of no use whatsoever and it will be terminated at the end of this year without any benefit from the overseas funding except perhaps a new police mess in Moresby etc.

Local anecdotal reports suggest those police being sent to PNG have no real cross cultural training or appropriate language skills and are virtually kept apart from their local equivalents due to their being unable to take part in any operational capacity. Exactly who is being helped here?

Hand out mentality never produces anything more than a desire for more handouts.

What is desperately required is an international training establishment that both those going to PNG and those coming from PNG can acquire language skills, cross cultural training and be assessed as to their suitability for the transfer or placement. We used to have just such an establishment in Mosman, Sydney however it was closed due to obvious conflicts with the ‘establishment’ at the time.

I think Julie Bishop is doing a great job and should be congratulated with what she is achieving given the obvious difficulties she faces at home not to those mention overseas.

Again, thanks for your comments.

It’s great to see continuing attention to this area of public opinion Camilla and Terence. It is clear from all the surveys carried out to date that there is a high proportion (70-80%) of Australians who support the Government providing aid but that this support is not strong when it is presented as against competing domestic expenditures.

This should not come as a surprise given humans’ strong focus on our own needs and those of our family and neighbourhood and the many close-to-home struggles that every family must deal with.

Surveys such as Eurobarometer show that the difference between those countries with high levels of aid and those without is not in the level of public support for aid but in the actions of a small number of political leaders who make decisions about budget allocations. Given that the 0.5% of GNI aid target would only require 2% of the federal budget, and therefore cannot greatly impact budget balances, it is clear that whether we have a generous or a miserly aid program is the outcome of decisions made by a few in executive government.

What the public thinks about these decisions is shaped by whether they are told “We can’t afford more aid, we have a budget crisis, it doesn’t work anyway and its often lost to corruption” or “We are a wealthy nation, we can afford to give more aid, we know that aid has saved and improved millions of lives despite the risk of corruption and we could help millions more people if we increased our level of aid”.

One day, hopefully, we will elect political leaders in Australia who have more generous hearts and consistently send the second, more factual, message to the Australian public.

Thanks, Garth. You’re absolutely right that there is not a direct correlation between levels of public support and political support for aid (or, at least, budget allocations to aid). It’s a topic that was beyond the scope of this discussion paper, but certainly something we are interested in exploring further. Ben Day also touches on it in this blog post.

I would suggest there’s also something of a ‘chicken-or-egg’ argument here — if budget allocations are ultimately dependent on who is elected to office, might raising public awareness and support for aid contribute to the election of more representatives who support that message too? We certainly can’t expect that raising public support will automatically translate into increased aid budgets, but I think it is reasonable to consider whether doing so could be an effective means of shifting the political discourse to one that is more amenable to aid.

Thanks again for your comment,

Camilla

Yes the chicken and the egg are both involved! I just wanted to emphasise that political leaders are in a powerful position to influence public perceptions about complex issues such as international development and what our nation can and cannot afford to do – these are not things that most people are very knowledgable about. If the public is told almost every day that we have a budget crisis and that we are living beyond our means it is not surprising that many people will think that we need to cut back on our “generous” levels of aid.

Paul, accuracy is important. The $100 million is for the entire reverse Colombo plan, over 5 years (and not just to PNG). It is not aid-funded.

Hi Stephen. I guess it depends on your perspective. If the Australian government (i.e. the Australian taxpayer) is funding this plan and the plan is involving our relationship with PNG then why is this not anything to do with ‘Australian Aid’? Aren’t we actually guilty ‘splitting hairs’? Exactly who is benefiting here?

If we are paying Australian students to gain experience in PNG, then maybe PNG should be asking the Australian government to pay them for providing ‘the PNG experience’?

The essential issue here is not whether this expenditure is either labelled ‘overseas aid’ or merely just part of our Foreign Affairs budget involving another nation. The issue is whether this is a waste of scarce resources and could and should the money be better spent actually helping our next door neighbour, who has been kind enough to offer this opportunity to Australian students when overseas aid has actually been reduced except for PNG.

Secondly, and most importantly, exactly how will 2 or 4 weeks experience with ‘PNG operational or line positions’ actually help Australian students without any substantial preparation for such a large cultural gap to cope with or any real language and appropriate cross cultural training to help them understand what they are in effect experiencing.

Then there is apparently no stated and pre set benchmarks or transparent assessment methodology of the program by either Australia or PNG. It will however undoubtedly help justify the legion of consultants and officials who will be tasked with managing the process but only have obfuscated responsibility should any ‘difficulties’ be experienced.

So if this isn’t ‘overseas aid money’ or apparently benefiting our Foreign Affairs, then why isn’t this part of the program funded through the Education budget? Isn’t the money merely just another ‘boomerang aid’ project that is intended to slip under the Australian public’s radar?

The New Colombo Plan also sends students to developed countries in Asia, like Singapore and Japan. We wouldn’t consider that ‘aid’. Why should it be any different for PNG? It’s a student mobility program, with no development objectives. The objectives are to build a base for longer-term engagement in the region by young Australians. The students that go on the short-term mobility placements are largely participating in a supervised ‘field school’ type credit, usually coordinated by their home university in Australia, or a semester of language training or something similar. They aren’t in-line or in operational positions at all.

It’s not aid, so it can’t be boomerang aid. Whether one thinks it is a worthy investment in regional engagement is another matter entirely.

Thank you Ashlee and Stephen for your responses. You are quite correct in that the New Colombo Plan initiative should not be labelled direct overseas aid.

I have now received and am studying a comprehensive policy statement from DFAT. The original PNG media release was perforce rather lacking in any real detail. I agree ‘Overseas Engagement’ might be a better and more appropriate terminology. The results of this initiative may well prove beneficial to Australia’s national interest. The extensive requirements for students who apply to join may select those attending tertiary institutions most suited to engage in this program.

My concerns as to whether they as representatives of Australia, are uniformly trained, prepared and transparently reported on is however another matter and I reserve my thoughts until I have thoroughly perused the official policy.

Notwithstanding, my original observations about surveys on whether Australians per se even think let alone know anything at all about ‘overseas aid’ still stand and are apparently unchallenged.