This blog is based on comments of the author at the October 27 Devpolicy Banking on Aid forum on the World Bank and the ADB.

The whole point of the World Bank and the International Development Association (IDA) in particular was to bring bilateral efforts together in a unified way. It has long been thought that the proliferation of trust funds in the Bank was undermining this goal. Now we have the data to show it.

IDA is the concessional arm of the World Bank, providing support to the world’s poorest countries. Every three years, bilateral donors agree how much they are going to give to IDA for the following replenishment period.

But donors also give money to the World Bank and IDA for specific projects and purposes – including technical assistance, debt relief and global funds – and these are managed through trust funds, which can focus on a country, a region or a global public good.

The World Bank’s AidFlows website opens up a whole statistical world of how aid is spent, including how much each donor gives to the Bank in the form of core contributions to IDA and how much is earmarked into trust funds. This blog will look at the questions of: who funds the World Bank? How much goes to core contributions and how much to trust funds? What are the implications of recent trends?

Patterns and trends in World Bank funding

1. Total funding – IDA plus trust funds – increased from $12 billion in FY2006 to almost $20 billion in FY2010. This is a two-thirds increase, but a declining proportion of global ODA.

2. Nearly all of the additional funds have gone to trust funds. IDA’s core contributions have remained flat since 2006 at about $7-8 billion. Meanwhile, earmarked payments to trust funds have almost tripled, from $4.4 billion in FY2006 to $11.4 billion in FY2010.

3. Only about half (49%) of funding is for core contributions, just over half is earmarked for trust funds. Overall between FY2006 and FY2010, the World Bank received $78 billion in funding from bilateral donors: $38 billion was for core contributions to IDA and $40 billion was for trust funds.

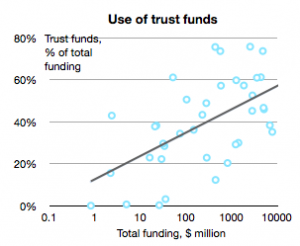

4. Bigger donors tend to earmark more than smaller donors, whereas the typical donor earmarks about 43% of their contributions to IDA. The two biggest donors – the UK and US, who account for 30% of World Bank funding – both earmark about 58% of their funding. The Netherlands, Norway, Russia and Saudia Arabia all earmark about 75% of their funding. Among the top ten donors, only Japan and Germany earmarked less than 40%.

4. Bigger donors tend to earmark more than smaller donors, whereas the typical donor earmarks about 43% of their contributions to IDA. The two biggest donors – the UK and US, who account for 30% of World Bank funding – both earmark about 58% of their funding. The Netherlands, Norway, Russia and Saudia Arabia all earmark about 75% of their funding. Among the top ten donors, only Japan and Germany earmarked less than 40%.

5. The number of donors has increased. But many of the World Bank’s contributors small donors, and top 10 account for 80% of contributions.

How does Australia fare?

Australia doesn’t make the top ten contributors: according to AidFlow data, Australia was the 14th largest donor to IDA over the period FY2006 to FY2010.

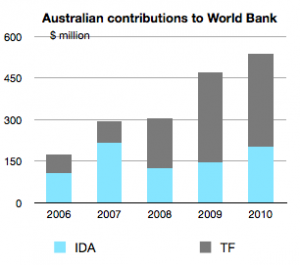

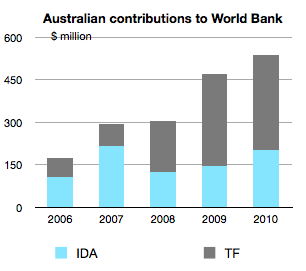

Despite being a smaller donor, Australia has a strong preference for trust funds over core contributions: more than half (57%) of Australia’s funding was earmarked, compared to 43% for the typical donor. We rank tenth when it comes to the proportion of earmarked funds to total contributions. Australia’s contributions to the World Bank have tripled since 2006, and nearly all of that increase has gone into earmarked trust funds.

Despite being a smaller donor, Australia has a strong preference for trust funds over core contributions: more than half (57%) of Australia’s funding was earmarked, compared to 43% for the typical donor. We rank tenth when it comes to the proportion of earmarked funds to total contributions. Australia’s contributions to the World Bank have tripled since 2006, and nearly all of that increase has gone into earmarked trust funds.

Australia’s ODA budget for multilateral agencies includes core contributions to IDA and a couple of trust funds: the Global Environment Facility and the World Bank Clean Technology Fund. But Australia’s multilateral numbers (about A$225m for FY2010) don’t tally with the World Bank data (over US$500m for FY2010), so presumably there are many more World Bank trust funds buried elsewhere in the Australian ODA budget.

1000 trust funds: A 2007 snapshot

The macro data from AidFlows doesn’t show what kinds of trust fund donors are supporting. But 2009 Trust Funds Annual Report provides a very interesting snapshot.

The WBG’s trust fund portfolio expanded rapidly between FY05 and FY08. The number of active trust funds increased from 839 to 1,020. Cash contributions to trust funds increased from $4.7 billion to $8.7 billion (an average of 23 percent) over the same period. Disbursements from trust funds grew from $4.1 billion to $6.7 billion (an average of 18 percent). Funds held in trust increased from $11.6 billion to $20.7 billion (an annual average of 21 percent) over FY05–FY08.

The trust fund portfolio continued to expand in FY09, albeit at a slower pace. The number of active trust funds increased to 1,045 at the end of FY09. In contrast with the upward trend recorded in preceding years, cash contributions declined by 3 percent in FY09 to $8.5 billion. Disbursements from trust funds amounted to $6.9 billion, up only 3 percent. A contributing factor to the moderate increase in overall disbursements was the decrease in Financial Intermediary Fund (FIF)* disbursements, from $3.5 billion in FY08 to $3.4 billion in FY09 (a 3 percent decline). Funds held in trust totaled $23.8 billion as of the end of FY09, up 15 percent compared to the end of FY08. New signed legal agreements amounted to $10.5 billion in FY09, bringing the total to $69.8 billion.

As in recent years, about two-thirds of the amount of funds held in trust and half of the trust fund disbursements in FY09 were accounted for by FIFs, for which the Bank acts as trustee but typically has no operational role. Some key FIFs established in FY09 include the Adaptation Fund, the Pilot Advanced Market Commitment and the Climate Investment Funds: the Clean Technology Fund and the Strategic Investment Fund.

As in FY08, the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (GFATM), the Global Environment Facility (GEF), and the Afghanistan Reconstruction Trust Fund (ARTF) occupied the top three spots in terms of cash contributions in FY09, receiving $3.1 billion, $696 million, and $525 million, respectively. Carbon Funds received the fourth-highest level of cash contributions, with $344 million. Together, these four funds received $4.7 billion, or 55 percent of all cash contributions to trust funds in FY09.

*Financial Intermediary Funds are typically multidonor initiatives to support global partnerships or programs.

The bilateralisation of the Bank?

Earmarking could also be thought of as bilateral aid delivered through a multilateral agency. Is this what is happening?

The picture is quite complex — some trust funds are more multilateral than others.

Some trust funds will always be there – like the Global Environment Facility — and if the Bank is funding international public goods then trust funds could be justified.

The issue is that there needs to be more scrutiny of World Bank trust funds — especially the Bank and recipient executed trust funds — given their large number and the huge volume of aid being channelled through them.

Firstly, there is a question of whether or not trust funds are the appropriate financing vehicle to address development challenges. One problem is that proliferation of trust funds isn’t costless. Trust funds fragment the Bank’s budget and operations, and undermine efficiency. They add to costs and stretch staff resources, because each requires special accounts and reporting that often duplicate the Bank’s core work.

Secondly, although this trend towards earmarking presumably reflects bilateral interests, it defeats the purpose of creating the Bank and IDA in the first place.

And thirdly, there are concerns about the accountability of trust funds both to the people they are supposed to help and to the citizens of those countries which are funding them. That there has been little awareness of the scale of the Bank’s trust funds until now highlights the value of aid transparency.

Meanwhile, IDA core funding is looking flat

After record rounds in IDA15 and IDA14, the World Bank may be struggling to get the big donors – US, UK, Japan, Germany, Greece and France – to open up their cheque books. The US and Japan have never been the most generous contributors to IDA, and other big benefactors face fiscal pressures and multilateral fatigue.

One of the reasons why donors aren’t digging deep, besides fiscal pressures, is that it is politically more difficult to make the case for multilateral aid. Not only are domestic stakeholders unfamiliar with the IFIs, it is also much more difficult to explain what happens to the money.

What can be done about it?

First, donors should move back to core funding, and this is particularly relevant for Australia.

Secondly, the Bank could improve the way that funds are earmarked. One option would be to create a virtual fund within IDA that would allow bilateral donors to allocate funds for specific themes, but without having to set up lots of parallel trust funds. Such approaches have worked well in developing country contexts. Virtual funds have been used to tag and track debt relief spending in both Uganda and Nigeria. This would significantly reduce the transaction costs associated with proliferating trust funds and ease the fragmentation problem. However, such an approach is not without risks. How much more earmarking might take place if the floodgates were opened?

Thirdly, this is the sort of analysis the G20 should be looking at, and encouraging increased funding for the IDA relative to trust funds. It should be part of the World Bank reform agenda, which hitherto has focused on reforming voting shares and board representation.

Fourthly, there is an opportunity at Busan later this month to have more discussion on the impact of different funding mechanisms on multilateral effectiveness.

While developing countries be getting more voice, for now bilateral money still talks. It’s time to have a proper debate on the best way to fund multilateral banks.

Matt Morris is the Deputy Director of the Development Policy Centre at ANU’s Crawford School.

Leave a Comment