If you want, there is a glass half full way of looking at the last six years of New Zealand aid giving. Sure, aid has ceased to rise as a share of GNI, sure NGO funding has been broken, sure serving New Zealand’s commercial and geostrategic interests is now an explicit function of our aid. And sure, we now fund cows without borders and training for businessmen who don’t need training. Yet these examples are not the whole story. There has been change, but there has also been a continuity of sorts.

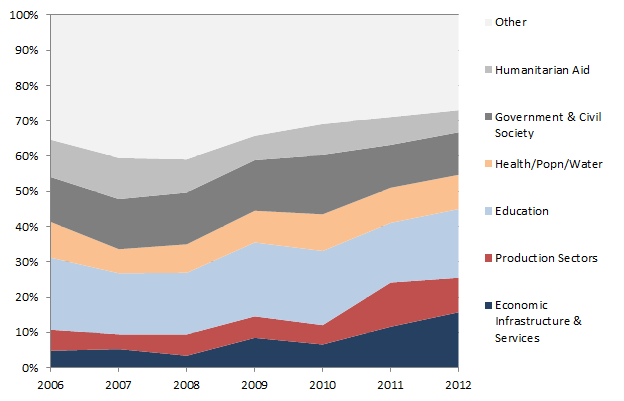

Take, for example, the sectoral focus of New Zealand aid. With the change of government in 2008 came a changed mandate for the aid programme: focus foremost on economic development. Economic development is good for the most part, but as a central focus for an aid programme it is mistaken. Mistaken because available evidence suggests aid is not particularly effective in fostering economic development, at least in certain contexts (one of us has argued this at length in a working paper and these two blog posts). And for this reason the change in mandate brought with it the worry that New Zealand’s aid efforts might be swallowed by a misplaced desire to have aid generate growth and growth alone. However, the most recently available sectoral data from the OECD suggest this hasn’t happened. The chart below is drawn from these data and plots New Zealand aid by sector across time. Clearly the bottom two sectors, those associated with economic development, have trended upwards significantly, but they haven’t yet crowded everything else out.

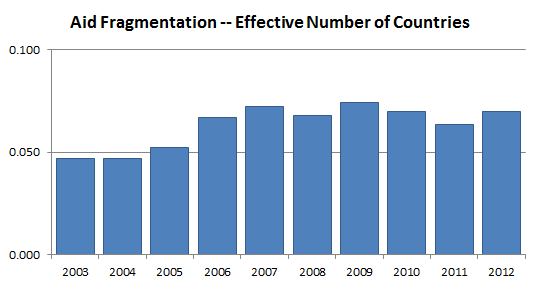

And while New Zealand’s aid is to some extent being diverted to further New Zealand’s interest, available evidence suggests one of the most egregious forms this might have taken has been avoided (for now at least). New Zealand is currently trying to secure a seat on the United Nations Security Council. However, unlike in Australia, this campaign does not appear to have led to increasing fragmentation of New Zealand’s aid effort, driven by the desire to curry favours with as many developing nations as possible in the lead up to the Security Council election in October. The chart below shows a Hirschman-Herfindahl fragmentation index of New Zealand aid across time (based on OECD DAC data). The chart and calculation method are explained in detail on page 36 of this working paper, but for now it suffices to note that a higher score on the chart reflects aid that is concentrated on a smaller number of countries (generally regarded as best practice in aid giving). The first years of the chart show New Zealand’s country concentration increasing post 2003 in response to earlier criticisms it had been too fragmented. And the good news is that, at least on the basis of the data currently available (and the caveat lector here is that data are only available up to 2012), this has yet to be reversed, even though we’ve been pursuing a Security Council seat.

And while New Zealand’s aid is to some extent being diverted to further New Zealand’s interest, available evidence suggests one of the most egregious forms this might have taken has been avoided (for now at least). New Zealand is currently trying to secure a seat on the United Nations Security Council. However, unlike in Australia, this campaign does not appear to have led to increasing fragmentation of New Zealand’s aid effort, driven by the desire to curry favours with as many developing nations as possible in the lead up to the Security Council election in October. The chart below shows a Hirschman-Herfindahl fragmentation index of New Zealand aid across time (based on OECD DAC data). The chart and calculation method are explained in detail on page 36 of this working paper, but for now it suffices to note that a higher score on the chart reflects aid that is concentrated on a smaller number of countries (generally regarded as best practice in aid giving). The first years of the chart show New Zealand’s country concentration increasing post 2003 in response to earlier criticisms it had been too fragmented. And the good news is that, at least on the basis of the data currently available (and the caveat lector here is that data are only available up to 2012), this has yet to be reversed, even though we’ve been pursuing a Security Council seat.

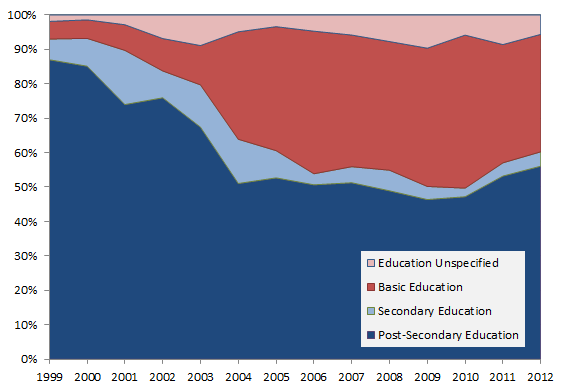

Another area where improvements that occurred in the first decade of the new millennium do not appear to have been reversed is in New Zealand’s approach to aiding developing countries’ education efforts. As can be seen in the first chart above, the education sector continues as it always has to get a significant slice of New Zealand aid. What changed between the late 1990s and 2008 was that New Zealand had a major shift in its education aid focus, away from scholarships and into primary education. Scholarships aren’t without worth, but it is likely that investing in primary education offers greater development dividends. The chart below shows this transformation.

Another area where improvements that occurred in the first decade of the new millennium do not appear to have been reversed is in New Zealand’s approach to aiding developing countries’ education efforts. As can be seen in the first chart above, the education sector continues as it always has to get a significant slice of New Zealand aid. What changed between the late 1990s and 2008 was that New Zealand had a major shift in its education aid focus, away from scholarships and into primary education. Scholarships aren’t without worth, but it is likely that investing in primary education offers greater development dividends. The chart below shows this transformation.

It also shows that post 2008 the share of education aid going to post-secondary education (which is primarily delivered as scholarships) has started to creep up again. Yet primary education still continues to receive a good portion of the aid involved, and at this point the situation is showing no signs of returning to the scholarship dominated focus of the late 1990s. This is also true in an absolute sense — in inflation adjusted dollar terms aid to scholarships has increased post 2008, but is still much lower than it was in 1999.

It also shows that post 2008 the share of education aid going to post-secondary education (which is primarily delivered as scholarships) has started to creep up again. Yet primary education still continues to receive a good portion of the aid involved, and at this point the situation is showing no signs of returning to the scholarship dominated focus of the late 1990s. This is also true in an absolute sense — in inflation adjusted dollar terms aid to scholarships has increased post 2008, but is still much lower than it was in 1999.

At a more micro-level, a careful read of New Zealand IATI data turns up some dubious sounding aid projects: funding a geothermal workshop in the Caribbean, farmer training in Chile, shearer training in South Africa, and technical advice to the Jordanian monarchy on a helicopter ambulance service. (Geothermal power and farming are areas New Zealand is seeking to expand its businesses’ global reach.) However, there is still much aid work of worth described in the IATI data, such as funding for disaster risk management in South East Asia and mental health initiatives in the Pacific, as well as the continuation of long-standing engagements, such as tax and education improvement projects in the Solomon Islands. And the very availability of the IATI data is itself a quiet triumph for aid transparency.

Reviewing all this, a fair assessment of the changes in New Zealand aid over the last six years would have to be that, while much has gotten worse, much has endured. And that which has endured has done so despite a trying political environment, a difficult Minister, and constrained fiscal circumstances. For New Zealanders this is good news, relatively speaking.

There are a number of reasons, including international norms, why at least some of what was good about New Zealand aid has endured. But one particularly important factor, we think, is under-appreciated. This is the aid programme’s staff.

The development of NZAID post 2002 brought with it an increased ethos of development, as well as a growing group of professionals committed to delivering good aid. And while staff turnover has been high, the belief staff have in delivering aid that delivers development appears to have endured, at least to an extent. And in the space offered underneath high-level political decisions, as well as through the opportunity to advise the Minister, this belief has stymied some of the potential damage done.

And this is the glass half full when it comes to New Zealand aid.

This is a part of the NZADDs coordinated series on NZ aid and development.

Terence Wood is a Research Officer at the Development Policy Centre and a PhD student at ANU. Prior to commencing study he worked for the New Zealand government aid program. Joanna Spratt is a PhD candidate at the Crawford School of Public Policy. She is also a consultant and coordinator of NZ Aid and Development Dialogues (NZADDs), with a background in nursing and international development.

Leave a Comment