If you’re reading this, you’ve almost certainly benefited from education. If you can read this, you very likely received primary education. Education is integral to development. And primary education is integral to education. Primary education is the launching point for most other study.

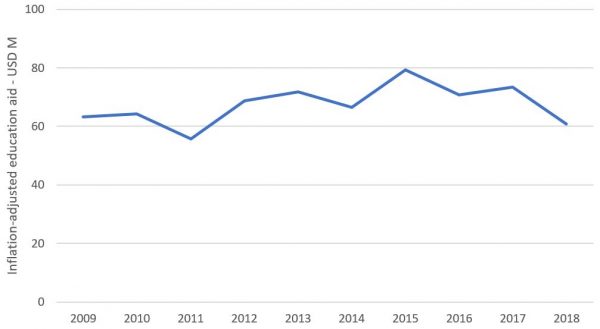

Between 2009 and 2018, the New Zealand government’s inflation-adjusted aid budget increased by about 41%. Over the same time, as the first chart below shows, New Zealand’s spending on education – which in 2009 received about one third of New Zealand’s sector-allocable aid – barely grew.

Total New Zealand aid spending on education (inflation adjusted USD millions)

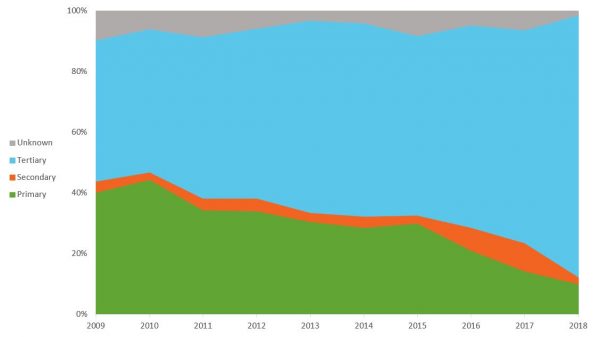

Yet, within New Zealand’s nearly-stagnant education spend, dramatic changes were afoot. The chart below shows what happened to primary education.

Inflation-adjusted aid for primary education

Funding for primary education collapsed. Why? How? What happened?

This chart provides the first part of the answer: as primary education fell, tertiary education spending consumed an increasing slice of the education pie.

New Zealand aid by education type

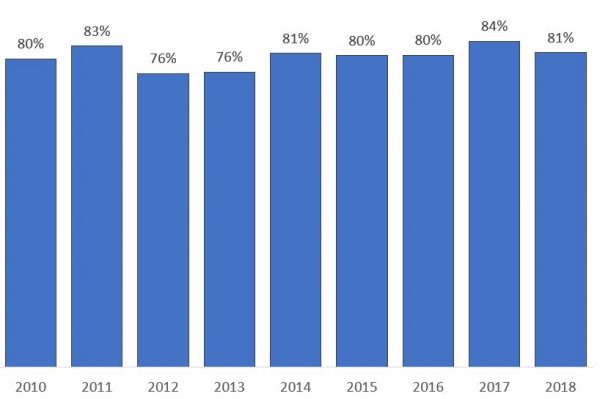

Perhaps that’s not so bad? Tertiary education is useful too. There are a number of tertiary institutions in the Pacific where good aid could help. But the rise in New Zealand’s tertiary education spending came from a different source. The chart below shows the share of New Zealand aid for tertiary education devoted to scholarships for study in New Zealand.

New Zealand aid for tertiary education: percentage spent on scholarships in New Zealand

The figure is approximate: it’s the best I can do with available data. Another attempt using different sources suggested an even greater scholarship focus. Also, New Zealand funds some tertiary scholarships at institutions like the University of the South Pacific (USP) in Fiji, as well as some scholarships for short term training in-situ. Such scholarships are not captured in this chart. If they were, scholarships might increase by as much as 10 percentage points.

Regardless, aid for scholarships consumes the lion’s share of New Zealand’s support for tertiary education. The increase in New Zealand’s focus on tertiary education stems from increased scholarship spending. Scholarships were the source of falling aid for primary education.

Scholarships aren’t a waste – I’ve met some impressive aid scholarship students. And an evaluation of New Zealand’s scholarships published in 2019 found some suggestive evidence of development benefits. But if the choice is between funding primary education and funding scholarships, primary education is more important. It’s more cost effective than bringing students to New Zealand and paying their living expenses while in-country (remember the bulk of New Zealand’s scholarships are for study in New Zealand). There is no evidence of a massive multiplier effect associated with scholarships: they help their recipients, but don’t lead to development transformations in their home countries. If primary education aid is given well, it will affect the lives of many more people than scholarships do.

Most of the scholarships New Zealand gives are restricted to study in New Zealand too, which means they are a form of tied aid – a fact Jo Spratt, Sharon Bell and I detail in Oxfam New Zealand’s new report on New Zealand aid. And New Zealand gives its scholarships with a view to currying geopolitical favour. On page 7 of the aid program’s evaluation of New Zealand’s aid scholarships, the evaluators are clear about this:

High-level outcomes identified in the Programme results framework are contributing to New Zealand’s strategic interests, the achievement of development outcomes for partner countries, and the strengthening of country-to-country ties.

Development is mentioned in the passage, which is fair. The aid program does try to promote development through scholarships, but it’s only one goal of three: the other two are about benefits for New Zealand.

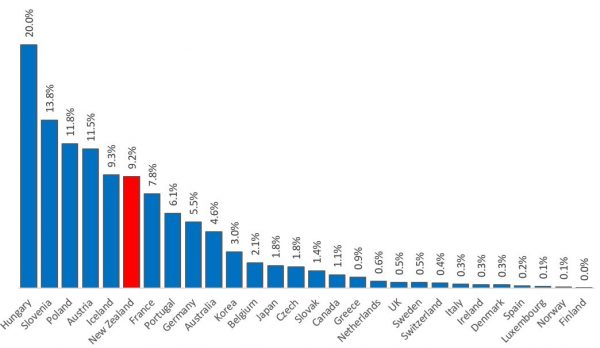

This doesn’t mean scholarships should be abandoned with all funding transferred to primary education. In New Zealand’s case though, re-balancing is required. The chart below shows aid devoted to scholarships in donor countries for most OECD DAC donors in 2018. (The US is missing as it doesn’t provide this information to the OECD.)

Aid devoted to scholarships as share of all aid

In 2018, the median DAC donor devoted just under 2% of its aid to scholarships. New Zealand was well above the median. Only five countries focused on scholarships more than NZ, and three of them – Hungary, Slovenia and Poland – are new donors and hardly models of good aid practice.

When myself and others voiced concerns about scholarships to the aid program in 2018, they told us they were planning to reduce New Zealand’s scholarship emphasis, but it would take time because many scholarships were for multiyear courses. This may well have been the plan, although numbers from page 44 of 2020-21 MFAT budget documents here don’t demonstrate a clear intent to decrease scholarships. Now, of course, coronavirus will have brought a rapid fall in scholarship spending.

What should New Zealand do once borders start to reopen? Returning to scholarships as usual would be a return to bad aid. New Zealand’s education spend needs to refocus: much less on scholarships and much more on other forms of study. Aid for primary education should increase. Aid for other levels of education such as secondary and other forms of training should also grow. I accept this can’t happen overnight, but the aid program needs to produce a publicly available plan, with a timeline and stated targets for improvement.

Education is integral to development. New Zealand’s aid for education is important. New Zealand needs to get serious about correcting the errors of the last decade.

[You can download data and calculations for my first three figures here. You can download data for my fourth figure here and my fifth figure here. Time series data of how much NZ spends on scholarships for study in New Zealand are here.]

Very helpful Terence. Agree re effect of the explicit self-interest in NZ development policy. Hopefully in the re-balancing, care is need to ensure appropriate curriculum (watch the creep of NCEA calibration) and the use of native languages.

Thanks Yvonne,

Some of that may be outside the hands of the aid programme of course, but I definitely agree any move back to primary education needs to be based on the approaches most likely to work in partner countries.

Terence

I was a participant in decisions regarding NZ’s support to education in PNG and Solomon Islands in the period you cite. Enthusiastic supporter as I am of data driven development, data analysis alone can’t address the specific country contexts in which decisions with respect to PNG and Solomon Islands at least, were taken. In PNG my recollection is that funding was reallocated because the proposed sector wide approach never got off the ground and the PNG government wanted to take stock and reassess its own approaches in education. In Solomons, support to primary education was a key intervention for NZ from the end of the Tensions. There were significant achievements after 10 years of support and my view was that we needed to build on these, not just repeat the same sorts of interventions ad infinitum. There were gaps that remained and review of the programme recommended focusing on delivering more support to schools themselves, especially in support and mentoring to teachers, as opposed to continuing a heavy focus on support to the Ministry in Honiara including consultant support.

Ultimately NZ has a relatively small aid programme, especially in comparison to the development opportunities that exist and the resources of others. As long as we work collaboratively with partners on the basis of their requests, support delivery of the changes our partners seek and don’t split our limited funds across too numerous priorities, I am not convinced that the particular sectors in which we work are that important.

Thanks Marion,

I agree, data cannot tell us the full story. Thanks for sharing your on the ground experiences from the Western Pacific.

It doesn’t totally surprise me that a Swap struggled in PNG, given the challenging governance context. Similarly, it doesn’t surprise me that elites lobbied for the type of aid most likely to benefit them and their families (scholarships).

In Solomons, I agree the education Swap was working pretty well, and that even so there must have been scope to recalibrate it — this would be good adaptive aid in practice.

Like you, I’m agnostic on sector. (Whether we focus our aid on education, governance, economic development etc, should be a function of what works and what’s needed, not some particular prior.)

That said, there is a clear need for education support in many countries we work in, and — within the education sector — no evidence whatsoever that scholarships bring the best development bang for their buck.

I also agree we shouldn’t fragment aid unduly across countries, projects or sectors. This isn’t good practice.

I have just one — data related — quibble though. In the Pacific we’re not a small donor: we’re the second largest. Which places a particular onus on us to get it right.

Thanks again for your comment. As always, great to hear your perspective.

Terence

This re-emphasis on scholarships wipes out the major re-balancing towards primary education in the Pacific achieved as a result of the ‘Towards Excellence in Aid Delivery’ report and work of NZAID. It represents the atavistic response of right-wing political thinking, where aid is an instrument of foreign policy and development effectiveness comes second to ‘national interest. For it to continue under a Labour-led government is a case of neglect, or absence of mind, and needs to be fixed.

Thanks Peter,

I agree, it’s an issue that urgently needs to be rectified.

Thank you for your comment.

Terence