In our previous post we showed that Australian aid projects are less effective in the Pacific than elsewhere in the developing world. Australia isn’t the only donor to suffer this problem. As two of us (Sabit and Terence) have shown in earlier work, the same issue exists for the World Bank and Asian Development Bank. It likely exists for other donors too. We don’t have enough data to test with other donors, but practitioner experience suggests a general issue.

This begs the question: what is it about the Pacific that leads to less effective projects?

In an attempt to answer this question, we used causal mediation analysis and applied it to a large multi-donor dataset. Full details of methods and results can be found in our latest Devpolicy Discussion Paper. (We strongly recommend you read the paper if you have any interest in research details; all we will provide here is a simple summary.)

To summarise very succinctly, our research findings included one surprise, one puzzle, and one profound challenge for aid practice.

The surprise

Going into this study, at least one of us (Terence), had a pretty strong hunch he knew why aid projects were less effective in the Pacific: poor governance in Pacific countries.

Yet we found no empirical evidence to support this view. In fact, we found the opposite.

We used a standard measure of governance in our study, the World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators, which cover traits such as the control of corruption, the rule of law, and effectiveness in delivering services.

Doing this we found that, globally, good governance was positively associated with more effective aid projects (see Table 3 in the paper). This was expected. Other studies have found the same thing. But – and this was the surprise – we also found that, using the World Bank measure, on average, governance is better in the Pacific than it is on average elsewhere in the developing world (see Table 4 in the paper).

In line with these facts, when we used causal mediation analysis to test how much country traits explained lower aid effectiveness in the Pacific, we found comparatively good average governance in the region actually helps project effectiveness. If governance in the average Pacific country was as poor as it was in the average country elsewhere in the developing world, aid project effectiveness would be lower still in the Pacific.

To be clear, our findings are for the Pacific as a whole. Governance in some individual Pacific countries, such as Papua New Guinea, is much worse than elsewhere. It is quite possible that a study focused on the worst-governed parts of the Pacific would produce different results. Nevertheless, the fact remains that, regionally, poor governance doesn’t explain why aid projects are less effective in the Pacific than elsewhere.

The puzzle

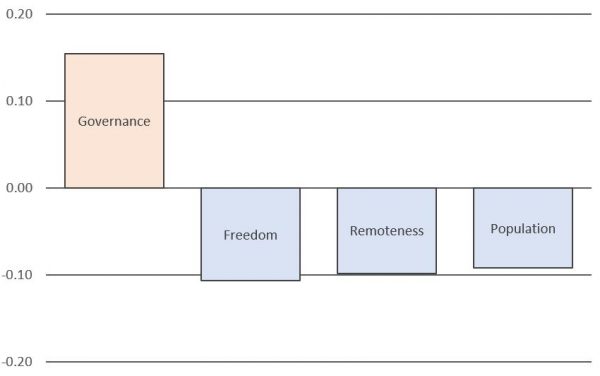

You can see the governance finding in Figure 1 below (which is simplified and taken from Table 6 in the paper). You can also see three other variables that pull in the opposite direction: freedom, remoteness and population. These are the three key variables we found that appear to explain why aid projects are less effective on average in the Pacific.

The first of these findings is a puzzle. On average, countries in the Pacific have greater civil and political freedoms (as measured by Freedom House) than countries elsewhere in the developing world. We also found a negative correlation between freedom and aid effectiveness. And when we applied causal mediation analysis, we found that greater freedom appears to be part of the reason why aid projects are less effective in the Pacific.

Figure 1: The role played by four key variables in explaining why aid projects are less effective in the Pacific

We’re not the first study to find that aid tends to be less effective in countries where freedoms are higher. And although some Pacific countries have issues, it’s true that civil and political liberties are greater in the Pacific than in many developing countries. Yet it is very hard to come up with any plausible explanation as to why more freedom would make aid less effective. (We controlled for possible confounding issues such as freedom reducing economic growth and growth being important for effective aid.)

It’s a genuine puzzle. We are confident freedom itself is not the issue. Perhaps the highly patronage-oriented politics found in the Pacific’s most democratic countries is the real source of this finding? More study is needed.

The challenge

We are much more confident of our final finding: the small size and remoteness of many Pacific countries appears to be a reason why aid projects are less effective. As the figure above shows, the empirical finding is clear. It’s also easily explained. Remoteness increases project costs, and makes management harder. Small size limits opportunities for economies of scale. Small populations reduce the potential pool of local counterparts.

The challenge though, is that remoteness and small populations are not going to go away in the Pacific anytime soon.

Rather, this is a challenge that donors will have to learn how to overcome. If donors want their aid to do justice to the needs of the Pacific, they will need to learn very carefully from their own work and genuinely pursue a context-appropriate, adaptive approach to giving.

Our own research has offered a high-level explanation of the constraints to aid effectiveness in the region. It’s a starting point. We don’t claim to be offering the final word. As researchers we hope to learn more. We hope others will too. More data and different methods will offer further insights.

What’s clear is that ensuring the effective provision of aid in the Pacific is not easy. Some of the key constraints are here to stay. It is aid practice that will have to change.

Read the full discussion paper here.

The authors call for donors to ‘learn from their own work’ and for ‘more data and different methods’ (i.e. presumably more research in the same field), but perhaps it would be more enlightening to look outside the aid industry and to engage across different fields of experience, theory and practice, including most importantly with Pacific people themselves and with the field of Pacific Studies. It would also be useful to start the discussion by framing this not as a Pacific problem, but as an aid problem. In fact, there has been a lot of discussion about this blog post in the Pacific studies community on social media. It would be so great to see some engagement across different forums and some sharing of the different perspectives.

Hi Angela,

Thank you for your comment.

I hope we are clear we don’t think this is a Pacific problem. There’s an empirical pattern, but our key finding points to an underlying issue that does not have anything to do with the people of the Pacific.

I like your suggestion of more engagement with Pacific people. To give donors due credit, they already do a lot of this, in ways ranging from government to government partnership, to community driven development projects. Nevertheless, more conversations would add much more, particularly conversations that empower people at the grassroots to have their say, and particularly conversations that carefully negotiate power dynamics within countries and communities.

Thank you also for letting me know about the social media discussion. Other than one comment on twitter, I was unaware of it. People are very welcome to tag me on twitter @terencewoodnz. I’m very happy to discuss more with people via email or Zoom or the like too.

Thanks again for taking the time to engage.

Terence