Enterprise challenge funds are viewed with instinctive affection by politicians and international development agencies. They use overseas aid to subsidise private investment in poverty-reducing business ventures in developing countries—ventures which have good medium-term prospects of commercial viability but would probably have been left on the shelf without subsidies.

Enterprise challenge funds are likeable because they are, at least in concept, catalytic and, relying upon private ingenuity, not technocratic. For aid agencies, they offer a more or less light-touch yet defensible way of allocating considerable resources. Since first appearing around the turn of the century in the UK aid program, these funds have proliferated. Funding controlled by around 20 contemporary funds, including Australia’s Enterprise Challenge Fund for the Pacific and Southeast Asia (ECF-PSA), is probably somewhere in the vicinity of $A400 million.

Given that these funds involve spending aid money in support of profit-seeking and sometimes multinational business ventures, on the basis of fairly inscrutable counterfactuals (would the venture have proceeded without the subsidy, and would it have succeeded?), one would expect them to draw at least some hostile attention. In practice, though, they fly under the radar. This is at least in part because they tend to be relatively small by comparison with socially-oriented challenge funds, and to allocate resources in quite modest parcels. (There is one very large fund, the $US200 million Africa Enterprise Challenge Fund, but even that has a maximum grant size of $US1.5 million.)

Criticism of enterprise challenge funds is rare—this pithy piece from an experienced practitioner, David Elliott of the Springfield Centre, is one exception, and this reflection from an implementing agency is another, milder one. Rigorous evaluation and full information disclosure, also, are not often to be seen. Australia’s ECF-PSA, which ended in 2013, is probably the strongest performer here, doing particularly well on both evaluation [pdf] and transparency. Its performance on the latter indicator is all the more creditable given the mixed outcomes reported.

It is not self-evident that there should be numerous ventures that actually fit the bill for enterprise challenge fund support, and indeed the thrust of Elliott’s criticism is that enterprise challenge funds tend in practice to move money by paying lip service to their advertised resource allocation criteria, with limited attention to what happens after said money is off donors’ books. The dearth of evaluative information on enterprise challenge funds makes it difficult for an observer to see whether and, if so, how such criticisms might be refuted.

Even if enterprise challenge funds are not always, or ever, implemented in line with their own advertising material, in principle they could be, with large impacts—and some home runs have been claimed, most notably M-PESA, a mobile banking platform which has achieved very wide reach within Kenya and beyond with some assistance from a UK-backed enterprise challenge fund. However, it can be argued that at least some of the design flaws and implementation weaknesses of these funds arise, not merely from an urge to disburse, but from a fundamental confusion about what international development agencies should be seeking to achieve by means of them, and how. This is the contention of the Development Policy Centre’s latest Discussion Paper, ‘Enterprise Challenge Funds for Development: Rationales, Objectives, Approaches’.

The discussion paper was informed by discussions within our 2013 working group on enterprise challenge funds and a workshop we hosted last October on lessons learned from Australia’s ECF-PSA, and expands on points made in this recent submission to Australia’s parliamentary inquiry into the role of the private sector in development. It argues that the main source of confusion in thinking about enterprise challenge funds is a failure to distinguish clearly between ‘enterprise development’ and ‘business modification’ objectives, and the rationales and instruments appropriate to each.

Enterprise development, in this context, involves reducing risks which impede the establishment or expansion of innovative, poverty-reducing, small- to medium-scale business enterprises. Here the rationale for public subsidies is that the level of risk associated with the investment is beyond what private financiers might reasonably be expected to bear, whether or not such financiers are actually present. Investment projects in this category should therefore be managed and outcomes assessed on a portfolio basis, with quite a high tolerance for failure at the level of individual investments.

For cost-effectiveness, enterprise development funding should generally be allocated to stronger firms with relatively favourable local enabling environments, without excessive post-financing engagement. Resources should be concentrated in certain countries and/or sectors so as to access the benefits of complementary investments in improving business enabling environments or in the provision of business support services, and also to facilitate review and evaluation. Ideally, resources would be provided as contingent or (success-linked) recoverable financing in order to allow recycling, and provided wherever possible in a way that leverages investment from private sources.

Business modification, by contrast, involves strengthening incentives for the adoption of poverty-reducing business strategies by established (often multinational) firms, through changes at the margin. Here the rationale for public subsidies is not that they reduce risk; rather, they compensate for missing public goods and provide incentives for firms—if they already have the disposition—to take pro-poor investment decisions, thereby facilitating changes in corporate strategy. The subsidy essentially has ‘nudge’ value, reducing the pain involved in making the change (or the cost if ‘cost’ is not interpreted in purely financial terms).

A business modification subsidy might or might not flow to a firm in the first instance but should not be conceived as benefiting the firm; the real beneficiaries are the poor suppliers, employees or consumers who become engaged in the firm’s supply chain as a result of the investment. Business modification proposals should be solicited from the widest possible field, without limitation as to site and sector. Projects supported should be few, substantial, sustained and closely managed, with a low tolerance for failure—which could have quite deleterious effects on corporate strategies and on political confidence in public-private partnerships for development.

Australia’s ECF-PSA, like other enterprise challenge funds, tried to pursue both of the above objectives with a single rationale, funding model and administrative apparatus. With a budget of about $A20 million over seven years, its most successful investments, particularly that in WING Cambodia [pdf], were of the business modification kind, yet inconsistent with the risk-reduction rationale offered for the program in its design document. In addition, these investments were approached in a light-touch fashion, on the basis that the firms concerned needed little outside help, whereas impacts on corporate strategies might have been substantially increased with more in-depth engagement aimed at deepening and extending partnerships.

On the other hand, the ECF-PSA’s enterprise development investments, particularly those in the Pacific island countries, were modest in their results yet extremely resource-intensive, with much support for capacity-building. Here the approach was far from light-touch, in large part because the fund was constrained to allocate a substantial proportion of resources in a region for which such a mechanism was not the right tool (the recently-established Pacific Business Investment Facility, a traditional equity financing and capacity-building mechanism to be managed by the Asian Development Bank with funding from Australia and other sources, appears more appropriate). In addition, the emphasis looks to have strayed from risk reduction financing toward simple gap-filling financing, perhaps in part because the ECF-PSA’s design imposed the perverse constraint that proponents should furnish evidence that their ventures were unable to mobilise financing from private sources.

In short, Australia’s ECF-PSA might have done better, if design constraints had allowed, to focus its enterprise development efforts on stronger local enterprises in Asia, with less post-financing engagement, and at the same time to engage much more fully with several flagship business modification ventures with potentially very large development payoffs. For example, it is conceivable—though obviously far from likely—that the Australian government would have been able, with heavier engagement, to influence the ANZ Banking Group, its original partner in the WING Cambodia venture, to build on the WING Cambodia model elsewhere, rather than selling off the business as it did in 2011. In fact, Australia’s ECF-PSA might have done better if it were not merely bifurcated but actually separated into two different vehicles, one to promote business modification, à la Business for Millennium Development (whose public-good character has been eroded by the Australian government’s insistence that it survive henceforth on industry funding), and the other enterprise development.

It is not for nothing that challenge funds, whether promoting enterprise development or business modification, hold such intuitive appeal for decision-makers—including Australia’s foreign minister Julie Bishop, who provided a rather firm advance commitment before assuming office in 2013 to the continuation of something looking much like the ECF-PSA. But these funds have not been around for long and, as many reviews have concluded, they have generally been established with neither sharp enough aims nor robust enough monitoring and evaluation arrangements. They have, to date, not really been given a fighting chance. In our view, future such mechanisms are more likely to succeed if they single-mindedly pursue one or the other of the above objectives, and shape themselves accordingly.

With the lessons of the ECF-PSA in hand, $140 million in funding for innovation in the bank and a strongly stated desire to help Asia’s private sector become a more powerful engine of poverty reduction, it would be surprising if the Australian government did not honour Julie Bishop’s commitment and put in place something recognisable as a successor to the ECF-PSA. It should do so, preferably putting in place not one but two, purpose-built tools to pursue the two quite different objectives distinguished above.

Robin Davies is Associate Director of the Development Policy Centre.

Thanks Robin. A useful contribution. In my tell-tale “pithy” style, I’d like to offer a short observation.

Giving Enterprise Challenge Funds a Chance. Youthful. Promising. Almost there. Really? If we’re to look forward to a glass half full, we should at least be clear that when looking back the glass wasn’t actually half empty. So let’s look back briefly…

Looking back a little, the ECF hangs almost entirely off its face saving mobile banking project (WING Cambodia). Evidently, this one project (of 23) accounts for 93% of total ECF beneficiaries reached, and 78% of the net income generated. Strip it out and the cupboard is almost bare.

Looking back a little further, according to a recent DFID report (“Meeting the challenge: How can enterprise challenge funds be made to work better”, April 2014) at least GBP 850mn has been invested in challenge funds over recent years. AusAID should be praised for subjecting the ECF to a CBA assessment, as none of these funds have come under anything like a similar level of scrutiny. But then again, why should they when they too can hang off their face saving mobile banking project (M-PESA)?!

Looking back even further, again according to the above mentioned DFID report, challenge funds can be traced back in the UK to 1714, and the Longitude Prize. How did this perform? Well, none of the major prizes were ever awarded. John Harrison, the esteemed clock maker, cracked the challenge of measuring longitude with his sea clock, then marine watch. He did this through his, and other private investment and endeavour. He was finally awarded £10k by the British Government 50 years later in 1764, when at the ripe old age of 71 his best work was behind him. Innovation? Additionality? Leverage? Really?

Youthful. Promising. Almost there. Isn’t 300 years long enough for researchers to learn something of value Robin?

John Harrison’s marine watch allowed sailors to find their way through the maritime mists. Who’s finally going to step up and help the development sector navigate their way through the deep layers of Challenge Fund Fog?

Thank you very much for this discussion Robin. It is good to see this research debate and discussion in the field of challenge funds.

It is important to consider the expected outcomes in advance for challenge funds and working in private sector development in general. Does the program intend to use the business as a vehicle to achieve development outcomes (such as innovative new products or to link to a particular supply chain) or to change the business to achieve these means?

The ECF was a pilot program which means that the objective was intentionally broad in order to feed into discussions like this around what works best and in what context. Importantly, DFAT provided additional resources for strong monitoring, research and external evaluation – these are all available on the ECF website (www.enterprisechallengefund.org).

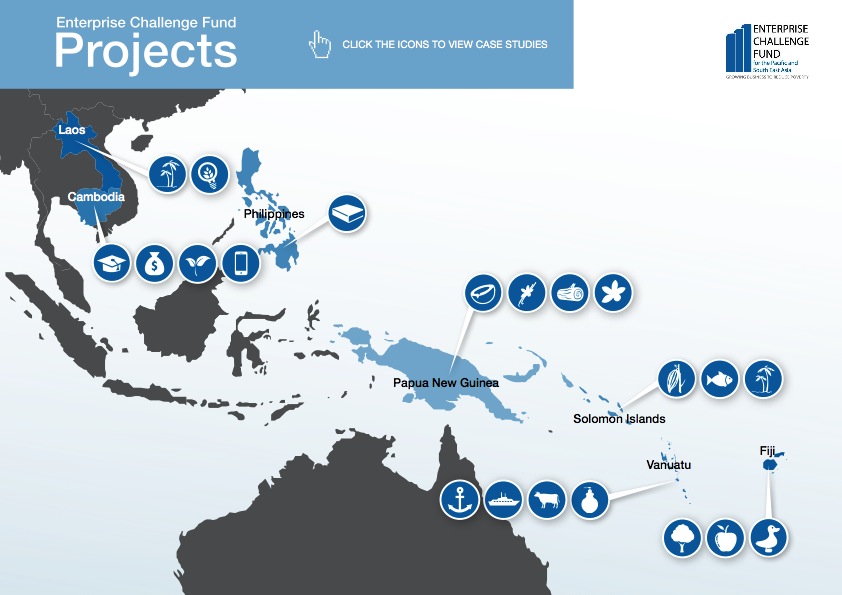

The ECF ran in both Pacific and South East Asia – two very different regions demographically, economically and with very different in business environments – and the results were similarly differentiated.

In the Pacific, the fund worked with more small-medium businesses. There were fewer larger businesses and the development outreach (also called employees, suppliers or customers by the companies) was smaller. Interestingly, the quality of outreach (the dollars that the beneficiaries earned) was higher. This approach was more consistent with an ‘enterprise development’ objective.

In Asia, there was a much larger pool of businesses to work, larger populations of beneficiaries and it was easier to have a “business modification” objective in this environment. An independent review found that a future challenge fund would work well in Asia – and potentially it could be used to incentivise companies to expand into more remote areas; innovate new products for the poor and could potentially go some way to address growing inequality.

This also raises a final point that it is important to consider the approach and the context not just at the design but during implementation. In smaller markets, operating a fund targeting only larger companies with a ‘business modification’ objective may quickly reduce the pool of eligible companies to work with – and as it progresses, the fund may need to consider either pulling out or changing objective to work with smaller firms.