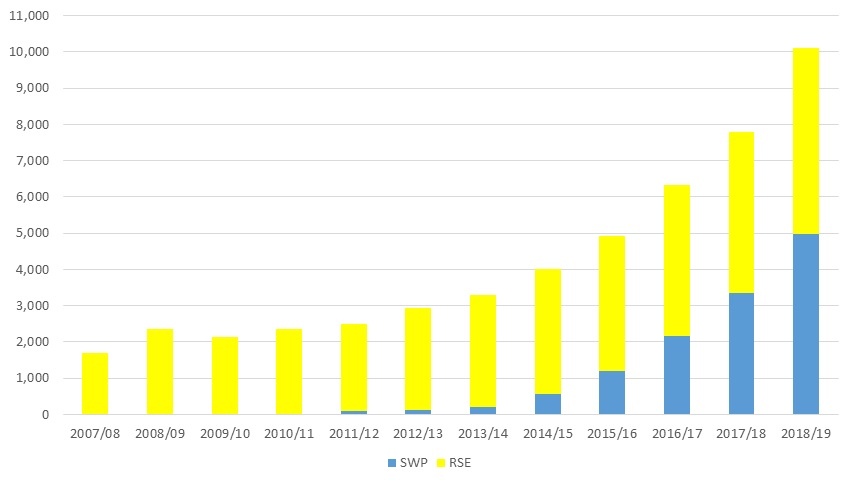

Vanuatu has been the most successful participant in Australia’s Seasonal Worker Programme (SWP) and New Zealand’s Recognised Seasonal Employer (RSE) scheme. The graph below shows how rapidly the number of ni-Vanuatu working in the two schemes has grown, from under 2,000 in 2007/08 to 10,000 in 2018/19.

Figure 1: Ni-Vanuatu SWP and RSE workers

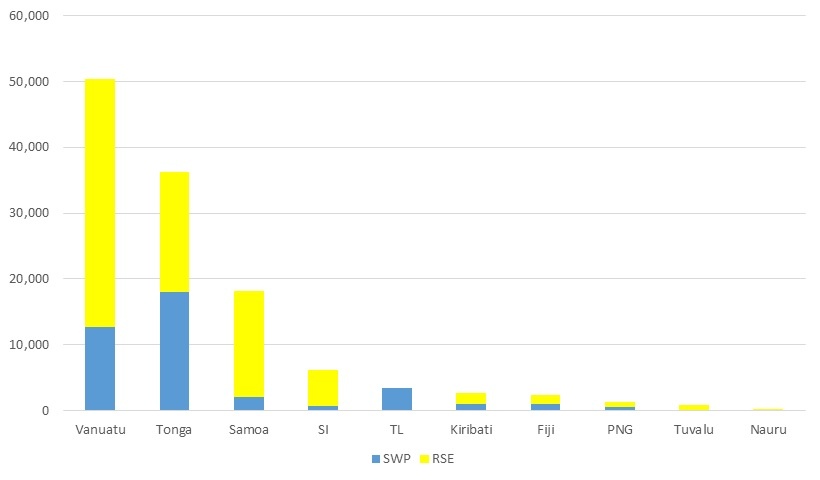

In fact, as the next graph shows, Vanuatu has sent more workers to the two schemes than any other participating country: just over 50,000. (It has always been the biggest provider to the RSE, and in 2017/18 took over as the biggest provider to the SWP.)

Figure 2: SWP and RSE workers by sending country,

from inception of programs to 2018-19

Given Vanuatu’s importance in providing seasonal labour, its decision, reported in the country’s Daily Post on 20 October, to do away with licensed recruitment agents sent shockwaves around the region. Vanuatu is the only labour-sending country in the SWP and RSE to license agents to recruit workers. Tonga, the second most successful seasonal labour sender, has a similar model, though it relies on unlicensed agents. Other countries place more reliance on a ‘work-ready pool’ arranged by sending governments, from which employers can recruit workers.

Vanuatu’s decision was announced by the new Deputy Prime Minister, Ishmael Kalsakau, who is also Minister for Internal Affairs and responsible for regulating recruitment agents. Kalsakau’s justification referred to the need to ensure fairness in the recruitment process to enable those from remote islands to benefit from access to seasonal work. The Deputy Prime Minister also said that the Government needed to raise revenue, mentioning a figure of 105 million vatu apparently raised by agents from charging employers for recruiting workers each year.

According to the announcement, the new recruitment process is to be carried out by the Government’s seven provincial administrators, who will ‘engage people from right around Vanuatu to connect them directly to the contracts they will be performing in Australia’.

It sounds like Vanuatu is planning to move to a government-led work-ready pool. If so, it is a major mistake, for several reasons.

First, employers have made it clear they don’t like recruiting through a work-ready pool. A survey of Australian SWP employers found that none of them ‘indicated the work-ready pool as their preferred method of recruitment’. It is not hard to work out why. Recruitment is all about trust. You want to hire people you know, or who are recommended by those you know. You can do that with agents, whether they are licensed or not, but not if you have to select from a work-ready pool.

Second, running a seasonal labour program is a lot of work for any sending country. Workers need police and health checks, visas, briefings, and airline tickets. Agents or other employer representatives can do much of this work, as they have been in Vanuatu. If you give all that work to public servants, the government will become a bottleneck. Vanuatu now sends more than 10,000 workers a year to Australia and New Zealand. There is simply no way the government can cope with this load without the help of agents.

Third, agents are responsive to the needs of employers because they are paid by employers once workers are recruited. They want to keep both employers and employees happy so that employers will use them the following season. Provincial administrators and their staff are busy government officials, who will have none of these incentives.

Fourth, Vanuatu doesn’t only rely on licensed agents; it also allows direct recruitment by employers. The largest New Zealand RSE employer engages its own staff in Vanuatu to handle recruitment. This is working well, but presumably would not be allowed under Vanuatu’s new model, thereby causing more employer dissatisfaction and bottlenecks.

Finally, we can simply look at the experience of labour sending countries over the last decade. The only country that has made a work-ready pool work is Timor-Leste, and even its approach was starting to show major problems before borders were closed earlier in the year. Other countries that have relied heavily on the work-ready pool (Papua New Guinea and Kiribati) have very few workers in the SWP or RSE. The two most successful countries, Vanuatu and Tonga, by contrast, have succeeded via flexible approaches with private sector engagement in recruitment.

No one would suggest that the governance of seasonal work in Vanuatu is not in need of reform. Too many agents have been granted licenses and not enough workers are recruited from the outer islands. However, there are far better ways to address these problems than to take a sledgehammer to a system that has delivered real success and replace it by one that has failed more often that it has succeeded.

If the Vanuatu Government wants more revenue from the SWP and RSE, it could charge workers an entry fee on return. If it wants more workers from the outer islands, it could make this a license condition for agents. The Government would be foolish to attempt to run the SWP and RSE singlehandedly.

The Government’s labour-sending unit (LSU) has been so stretched it hasn’t even been able to keep track of all the workers recruited for the two schemes. Vanuatu is the only one of the three major SWP sending countries not to have a government official based in Australia to look after worker welfare. These should be the government reform priorities, not nationalisation.

The timing is particularly bad, as the announcement will create uncertainty for ni-Vanuatu workers already in Australia about their future as seasonal workers. They will lose confidence in whether they will be chosen to return to Australia in future seasons. With the closure of borders, absconding has already become an issue with workers in the SWP. With this announcement, it will likely increase.

It is very hard to believe that Vanuatu would adopt a model that has failed elsewhere. If it does, employers would likely move away from Vanuatu once international borders reopen and look for workers elsewhere in the Pacific. There is massive competition for SWP and RSE positions across sending countries. If Vanuatu does go forward with its announcement, other sending countries will be the main beneficiaries.

Note: In both graphs, the number of workers is estimated by the number of visa approvals. The same person working in two seasons is counted as two workers.

Sounds great, BUT THE TWO COUNTRY GOVERNMENT NEED TO PAY VANUATU ROYALTY.

Thank you. I think even more so the workers and prospective workers need to be heard and develop agency. In all of this to date they have had little of either.

Hoping whatever changes are made work for their benefit.

Whether you like it not vanuatu is our country and decision taken is to benefit

The whole nation. It’s seems that the agents have been fooling workers all this years. This is The best approach.

Tanks for updates very valid words

Why suggest a solution that takes money out of the hands of the worker?

That would be unfair given the spurious deductions they have to pay weekly, as well as the 15c in every $1 that they pay to the Australian Government in tax.

Thanks for your comment on our suggestion that if the Vanuatu Government wants more revenue from the SWP and RSE, it could charge workers an entry fee on return.

I think that SWP and RSE workers would be happy to pay a tax to their government if there was a direct benefit for them. In particular, ni-Vanuatu workers have lacked the support of liaison officers while working overseas. The tax could fund one or more liaison officers to provide this support. A levy would also enable workers to hold liaison officers accountable in terms of their responsiveness and ability to resolve problems on the ground.

A levy would also give workers the right to demand greater accountability more generally. A debriefing session on their return would give workers the chance to give feedback on their approved employer, their workplace supervision and the performance of the government-funded liaison officer. The ESU conducted these debriefing sessions in the early days of the RSE but they have long since ceased.

The proposal is a good one. From the people I know in the scheme, especially now with the unusual circumstances, some agents have made no contact at all with their participants, and there has been major confusion with little or no knowledge of where to go for advice and information. The current mob here could provide a huge amount of feedback on the challenges they’ve faced.

But I wonder really how many would be happy to be taxed again on the amount they earn through truly hard labour.

All of the people I know get less than half their gross weekly income in their bank accounts, after 15% goes direct to Australian Government, health insurance, $140 to $170 on accommodation regardless of the market rent and utilities that would apply to that accommodation in normal circumstances and exorbitant transport costs.

This applies not just to weekly but to their annualised payments.

In addition there’s no guarantee that the Vanuatu Government would use any revenue for such a good initiative…. As you know they would have many competing priorities.

It’s a pity that despite some really good agents there are some that have spoilt the reputation of agents through inaction and other practices.

Jean, thanks for your response. It is my view that the agent recruitment system does need governance reforms to make it more effective. I reached this conclusion after spending some time collecting feedback from agents by email, talking to them and to workers while preparing a report for the Government in 2018 on a framework for a new national labour mobility policy.

The agents now need to work out themselves as a group what reforms they think are needed and to propose them to the government.

I’d just add to Richard’s response that you could charge employers to fund government SWP services, but then employers would be more likely to hire from other countries, so fewer ni-Vanuatu would get to work on the SWP.

Stephen